Why are cod struggling to recover in New England? Climate change is part of the answer

Climate change is preventing cod from rebuilding in New England. Many scientists and fishermen believe this, and a study released last week in Science by Dr. Andrew Pershing from the Gulf of Maine Research Institute and his co-authors provides new evidence to support this claim.

A brief history

Cod, an iconic species and a mainstay of New England fisheries, were overfished for decades, with catch levels peaking during the 1980s. In 2010, the fishery transitioned to the current quota-based management system under an Annual Catch Limit (ACL). Bringing cod under a fixed quota system should have ended overfishing and brought about recovery of the stock, but in recent years the biomass of Gulf of Maine cod has continued to decline, and was estimated in 2014 to be at just 3-4% of sustainable levels. Fishermen are catching fewer cod every year, and the quota is now so low that most fishermen actively try to avoid catching them. Yet despite these very strict catch limits, Gulf of Maine cod have not rebounded and the region’s fishermen are suffering devastating economic consequences.

Strong evidence that climate change is reducing cod’s ability to successfully rebuild

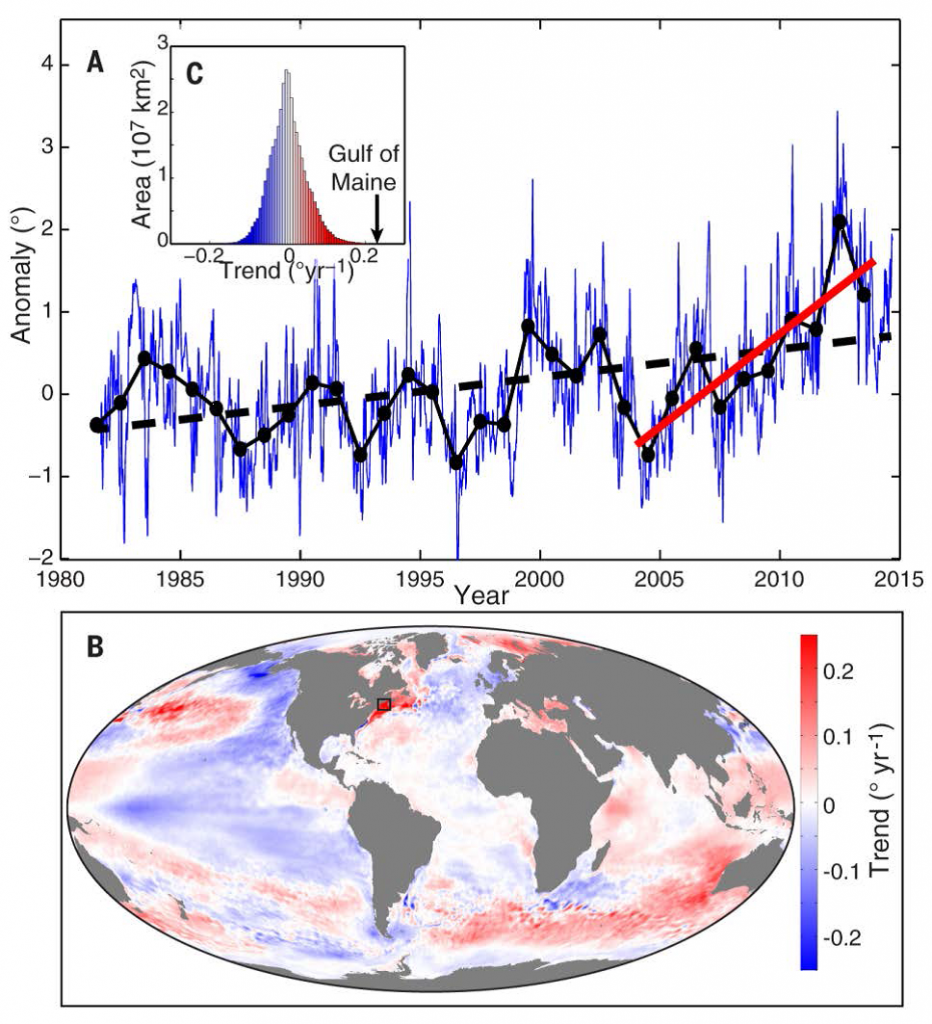

The Gulf of Maine is at the forefront of climate change impacts – the region has seen water temperatures increasing steadily over the last decade as a result of climate change, and is known to be warming at a faster rate than 99.9% of the world’s oceans.

As the Gulf of Maine becomes warmer, it becomes less suitable for cod. The study found that many juvenile cod appeared to be dying before reaching adulthood when they become large enough to spawn successfully and be targeted by fishermen. The authors suggest this could be in large part due to an increase in predation on young cod. Warmer waters mean an earlier spring and a later fall, which could result in more migratory predators present in the region for a longer duration each year. Elevated temperatures could also mean cod may have additional energy requirements, reducing their likelihood of survival.

Fisheries management needs to account for environmental changes

At the same time, fishing pressure was not sufficiently reduced to account for these changes, meaning that despite large cuts, Gulf of Maine cod still could not rebuild, even though fishermen were not exceeding their quotas. Fisheries stock assessments, used to determine how many fish can be taken each year, do not typically account for temperature and other environmental variables, and thus they consistently overestimated the size of the population. How much water temperatures continue to increase in the near future, and how fishery management strategies respond to these changes, will determine whether and how quickly the cod fishery can return to one that is sustainable and profitable in the coming decades.

So what can be done to address this problem?

Fisheries managers and scientists need to take temperature and other ecosystem factors into account when conducting stock assessments and setting catch limits not just for cod, but in all stock assessments to avoid discovering too late that we’ve been setting catch limits incorrectly. We can no longer assume a static environment in which fisheries can return to where they were in the past. To that end, EDF has an ongoing research project with our partners at the University of California Santa Barbara to better predict what fisheries in New England might look like in the future under climate change.

We also have a handful of studies underway directed at integrating climate change into fisheries science, including reviewing past groundfish stock assessments to determine whether incorporating climate change would have improved the results, and developing recommendations for how to better incorporate environmental change into stock assessments in the future. Additional research is needed to better understand the impacts of climate change on fisheries. NOAA should increase opportunities for fishermen and scientists to work together under cooperative research programs to gather real-time data on water temperatures, fish behavior and abundance, and other factors to observe these changes as they are happening.

Finally, consumers can seek out healthy, abundant groundfish stocks, including haddock, pollock, redfish, and hake, to support the struggling groundfish fleet in the absence of healthy cod populations. We are supporting efforts to bolster markets for underutilized fish to support fishermen. By promoting better science and management that is responsive to our changing environment and by shifting our focus onto healthy stocks, New England can support a resilient, profitable groundfish fishery and thriving fishing communities once again.