As fishermen around New England will be the first to point out, this summer, much like last year, has been abnormal. The ocean waters were warmer and cod, haddock, and flounders—the mainstay of our fishing industry for centuries—are increasingly elusive. There’s plenty of blame to go around, including decades of mismanagement and overfishing, inexact science and a mismatch in abundance of certain predatory species. Looking beyond these factors, the impact of climate change on fisheries is another factor driving fish abundance that’s worth a hard look.

The level of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere has now exceeded 400 parts per million, contributing to rising ocean temperatures. Some of the fastest increases in the last few decades have occurred in the Northwest Atlantic, and 2012 registered the largest annual increase in mean sea surface temperature for the Northwest Atlantic in the last 30 years.

It is clear that climate change is disrupting New England’s fisheries right now; it is no longer an abstract, future scenario.

In the face of this evidence, fisheries managers need to factor in climate change alongside fishing effort and other elements when determining how to manage and rebuild fish stocks. The impacts of climate change can prevent fisheries management inactions from rebuilding fish populations, and conversely, excess fishing pressure can hinder the ability of a fish population to adapt to changes in climate. As I have written recently, a network of well-designed closed areas represents a promising management strategy to address the effect of climate change on fisheries.

Warming waters, shifting populations:

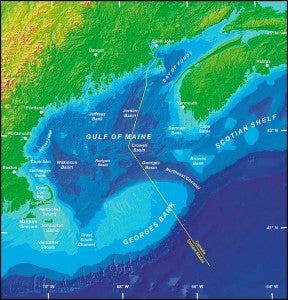

The mechanisms by which shifts in water temperature affect fish populations are not completely understood, but temperature driven changes have been observed in various species. Species’ response to climate change may be manifested as a shift in geographical distribution of the species, an expansion or contraction of the species’ range, or a change in depth distribution. Shifts in abundance are likely to be most apparent for species on the southern end of their range, and indeed shifts in fisheries distribution caused by warming waters are already taking place in the Northwest Atlantic. One study found a number of fish stocks in New England have shifted their center of biomass northward over the past 40 years.

Climate-driven shifts have been documented for cod in particular, one of the most economically, ecologically, and culturally important fish species in New England. Cod stocks on Georges Bank and in the Gulf of Maine are at the southern end of their range in the Northwest Atlantic. Temperature influences the distribution of cod in the region, and warmer water temperature has also been linked to a decline in productivity in the Gulf of Maine.

While climate change may be affecting iconic species in New England fisheries, other species may also be shifting their distribution north to areas where they are not typically found. Several news articles in local media outlets this summer featured fishermen who described the changes they’ve witnessed in the distribution of fish species. Fishermen in Maine have seen increasing numbers of black sea bass and longfin squid – species not traditionally seen in the Gulf of Maine – while fishermen in Rhode Island are catching warm water species like cobia and Atlantic croaker.

Finding management solutions to uncertain changes:

The New England Fishery Management Council is currently working to design a new network of closed areas in the region, which would build resilience in the fishery by providing protection for fish, as they shift their distribution and as they adapt to a changing ecosystem, thereby protecting fishermen’s businesses in the long-term.

Closed areas can protect the territory most critical to the productivity of target fish species, including important but vulnerable habitats, areas important for foraging and areas that harbor critical life stages like large spawners and juveniles. Refuges from fishing pressure can provide further resilience for fish species faced with a changing environment and a well-designed network of closed areas provides important stepping stones for fish species shifting their distribution in response to warming waters.

One way to increase resilience to climate change is to rebuild the population structure for overexploited fish stocks. Fishing pressure typically targets the largest (and oldest) fish. However, large, old females are typically more successful breeders, producing a much larger number of healthy larvae, and spawning more frequently than their smaller counterparts. Closed areas designed around known spawning grounds or other areas where these large females congregate can preserve a population of older, larger fish within the stock, reducing their exposure to fishing pressure and allowing them to reproduce and contribute to stock rebuilding.

Climate change needs to be considered when designing properly functioning closed areas, understanding that both fish and fishing effort may shift as a result of environmental change.

Uncertainty is inherent in both the marine ecosystem and our management of fisheries, and creating closed areas can ensure some level of insurance against this uncertainty. A closed area network for New England’s fisheries should be broadly distributed throughout the region to provide refuges to fish, particularly as stocks shift northward from their traditional areas of abundance. A well-designed network of linked closed areas can allow species distribution to shift in response to climate change, but remain at least partially protected. This will be important not only to fish but to fishermen, creating the resiliency needed in a healthy fishery to support the long-term interests of the fishing industry.

This closed area network can provide resilience to climate change in the near term, and can be adapted to meet changing conditions as species shift. The Council needs to consider climate change when making decisions about developing this closed area network. They should not miss the opportunity to take a positive step in the direction of managing for a changing climate.

Dr. Sarah Smith is a member of EDF Ocean’s Spatial and Ecosystems Initiatives team