Unseen Victims of the BP Oil Disaster

Floating mats of seaweed, known as sargassum, are home to a wide variety of ocean life. Credit: Steve W. Ross (UNCW), unpubl. data. |

The daily count of sea creatures dying from coating with oil on the surface of the sea, or on the beaches, continues to rise. We see sea turtles, sea and shore birds, and marine mammals, familiar creatures to us all.

As sad as these deaths are, the death toll is massively greater for animals not quite as visible, because they are small, living among marsh grasses, or under the surface of the sea, out-of-sight and thus out-of-mind. The full litany of the dead is deeply disturbing.

Surface currents carry valuable life

The surface waters of a healthy Gulf swim with life, much of it too small to see. Larvae of shrimp, crab, and other shellfish, and many familiar seafood fishes, spawned at sea, drift toward nurseries in coastal marshes and other shallow waters. Floating mats of seaweed, called sargassum, provide key habitats for babies of many species, now hopelessly contaminated. The interior and underside of these seaweed mats – under normal conditions – are wonderlands of life, as every offshore fisherman knows.

|  |

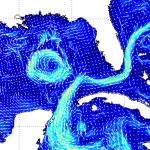

| The evolution of the Gulf Loop Current from a strong downstream delivery phase on May 7 to a cutoff eddy phase on June 11, temporarily detaining oil pollution. Credit: NWS. | |

The Gulf Loop Current – a term now commonplace– is a superhighway in the sea for spawned babies of giant tunas, swordfish and other billfishes, groupers, snappers and other reef fishes, and even for hatchling turtles. These creatures ride the current —our version of Nemo’s East Australian Current— toward adult habitats, at risk as they pass through the ‘kill zone’ of oil in the northern Gulf.

See an animation of the current loop here and see a video of the oil spreading here.

Luckily, the chance development on June 1 of a cutoff eddy—a normal phase in the evolution of the Gulf Loop Current, where the current bends deep enough to interact with itself, ultimately cutting off a spinning gyre in the northern Gulf—has delayed the otherwise rapid delivery of oil pollution to the pristine coral reefs, mangrove swamps and seagrass beds of northern Cuba, the Florida Keys and beyond. Delivery of oil downcurrent to those habitats remains likely, as the Gulf Loop redevelops. In fact, the weathered oil currently held in the cutoff eddy will likely drift northwest towards the Texas coast.

The beauty, and now oil, down below

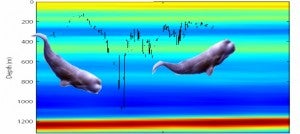

Under the surface, hovering clouds of oil pollution drift with the currents, and threaten perhaps the least known elements of this magical world. At middle depths, a profusion of life – shrimps, lanternfish, jellyfish and squids –create a layer of life so rich it appears as sonar returns to surface ships, earning the name “deep scattering layer” to scientists. This rarely imagined world of the deep – key prey for surface diving whales, dolphins, sharks and tunas – is now being contaminated twice, as oil pollution rises to and through it, and as sinking particles carry toxicants back downward. It is no surprise that sperm whales and other deep-feeding life forms we cherish are now numbered among the dead.

Deepwater treasures contaminated

On the bottom, the corals and worms get the short end of the slick. The deep-origin oil spewing from the crippled well is polluting deepsea wonderlands that are just now being discovered, notably majestic and ancient deepwater coral reefs. The vast majority of the oil that remains in the sea will ultimately find its way to the seafloor, where worms and other sediment-eating life forms will ingest it, be ingested in turn, and continue contaminating food webs – and the very web of life – for generations to come.

This spill impacts you, too

Put all together, every important part of the broader Gulf of Mexico marine ecosystem – upon which so many people rely for their income, and their way of life – is taking many potential knockout blows. Productivity of key seafood species could be depressed for years if not generations to come. Special care will be required to ensure that Gulf seafood remains safe. There is plenty to cry about, both on the surface and in the unseen places in the deep.

Never miss a post! Subscribe to EDFish via a email or a feed reader.

One Comment

Isn't there anyone investigating the status of the oil in the reefs? This was mentioned on CNN months ago and I've been looking for an update as the oil spread further east but can't find anything new. And I do hope someone is working on plans to restock the smaller members of the food chain. It would be nice to hear something proactive being done for a change. So far the flooding of fields in hopes to keep migrating birds away is the only such story I've heard

Also, many of the larger animals are also not being seen or rescued. There are many marshes and islands in Louisiana that are not even being visited for clean up or rescue. In addition, Fish and Wildlife insist on sticking to the usual policy of not rescuing birds if it 'risks disturbing other nests.' But at this point those rookeries are doomed. And the tides have recently been extra high. High enough to wash away cleanup crew tents on Grand Isle. Surely high enough to wash oil further onto those rookeries where they refused to rescue oiled birds. Not to mention that it often is possible to retrieve birds without disturbing others and it should be evaluated case by case.

If you really are involved in the response, please do something about this. They do not have enough people doing the rescue and rehab of the animals even though there are many organizations that have worked oil spills in that area for decades and have the people, experience and equipment to do so, but are not being allowed to participate. Instead groups from elsewhere in the country have been brought in and the contractor, O'Brien sent out ads to hire workers without experience. The Louisiana coastline is vast and should be divided into zones with a facility and group in each. Please look into Grand Terre and Queen Bess islands along with the Least Tern nests cleanup workers keep driving and trampling through despite so much effort to stop them.

Please refer to this blog for more information on what is really happening with the marsh cleanup and wildlife rescue in Louisiana: http://birding.typepad.com/gulf/