Credit: Steve W. Ross (UNCW), unpubl. data.

Among the unseen and uncounted victims of the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico are the inhabitants of the ancient deepwater coral reefs that lie under the still-growing plume of oil. Newly discovered, and still largely unexplored, these “rainforests of the deep” may become polluted and degraded before we even know exactly where they occur.

Deepwater wonders

Deepwater corals were first discovered in U.S. waters in the 19th century, during the early voyages of discovery, but only in the modern age of deepsea submarines and remotely operated vehicles did exploration truly begin.

Credit: Steve W. Ross (UNCW), unpubl. data.

As exploration has unfolded, scientists have been amazed at the extent and character of these underwater wonderlands, with new species being discovered with nearly every dive, including unknown forms with the potential to contain novel chemicals with pharmaceutical applications. A cancer cure may lie in the darkness of the deep sea.

Additionally, the branches of millennia-old corals have recorded in their layers an unequalled history of the recent life of the planet, including deepsea conditions that will allow ancient climates to be modeled.

Gulf of Mexico coral reefs

Credit: Geoplatform.gov |  Credit: USGS |

| Click images for larger view |

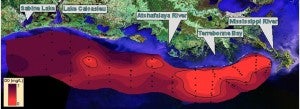

The best-known deepwater reefs in the Gulf are located in the Viosca Knolls region, on the northern edge of the DeSoto Canyon, only twenty miles from the blown-out BP well, and on the edge of the Mississippi Canyon west of the blowout site. In addition, there are known deepwater reefs off the West Florida Shelf and elsewhere in the Gulf. Exciting research is currently underway in the Gulf, including the deployment of “lunar lander” data recorders for year-long stays on the bottom near the reefs, which could provide badly needed baseline information for pre-blowout conditions.

See a thorough analysis of coral reefs in the Gulf, Southeast and elsewhere here.

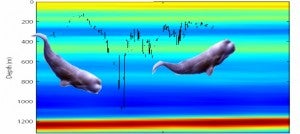

Toxins raining down on corals

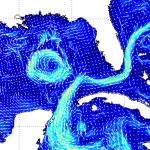

The deepwater origin of the BP oil disaster, the use of dispersants at the wellhead, and the resulting development of sub-surface plumes of oil-based pollution floating and drifting with sub-surface currents, mean that Gulf deepwater corals are at serious risk of direct degradation from the broken well, including a wide array of materials that would likely prove toxic to them. Normally, at least some of the toxic substances from an oil spill would evaporate as oil sits on the ocean surface, but in this situation, many of the toxins remain dissolved, emulsified or otherwise entrained in near-bottom waters and middle depths, drifting with the currents and potentially exposing deepwater reefs. Coral’s naturally slow growth rates and uncertain reproduction means that any damage would be difficult if not impossible to remediate or offset.

To make matters worse, oil that does make it to the ocean surface doesn’t stay there. While some of the toxic material on the surface is burned or evaporated, much is again treated with dispersant chemicals, forming smaller droplets that easily stick to debris raining into the abyss. In addition, a significant fraction of weathered oil also ultimately sinks back to the depths of the ocean. Although estimates vary widely, the best guess is that 25-30% or so of the oil from the 1979 Ixtoc 1 blowout in Campeche Bay in the southwestern Gulf sank to the bottom.

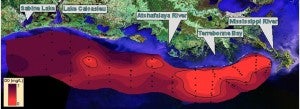

Credit: LUMCON

Another real threat comes from the decomposition of oil-based organic matter under water. “Dead zones” are well-known in the shallower waters of the northern Gulf, driven mostly by nutrients and organic matter from the outflows from the Mississippi River. In this case, underwater “dead zones” at a variety of depths are likely, and could add an additional punch to fragile ancient corals.

Protecting deepwater treasures

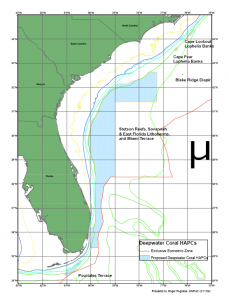

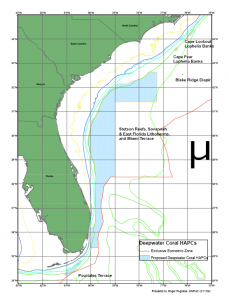

Credit: SAFMC

Ironically, as Gulf coral reefs face an uncertain future, thousands of square miles of reefs are being protected in a new program nearby in the Southeast Atlantic. I had the great privilege of chairing the panel responsible for this magnificent advance.

Over the past decade, a unique collaboration of academic researchers, managers and fishermen have worked together to craft a landmark protection program for 23,000 square miles of deepwater reefs stretching from North Carolina to Florida. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration approved these protections just this month, which will protect the coral reefs against fishing and many non-fishing threats. While this designation by itself does not guarantee that oil and gas drilling could not occur there, it means that risks to those corals would have to be taken into account during lease sales and other project planning and design.

Two of the many researchers instrumental in securing these coral protections—Dr. Steve Ross from UNC Wilmington and Dr. John Reed from Harbor Branch—have each published their corals research online.

Corals in the crosshairs

The bottom line, sadly, is that ancient Gulf of Mexico coral reefs lie in the crosshairs of oil pollution from the BP oil disaster and it will be some time before scientists are able to begin damage assessments. Research cruises scheduled for September may begin that process.

Never miss a post! Subscribe to EDFish via a email or a feed reader.

I remain extremely concerned about what has happened to the out-of-sight, underwater ecosystems of the Gulf of Mexico, especially at middle depths and on the bottom. These little known but ecologically vital elements of the ocean have been heavily exposed to oil-based pollution, both rising from the bottom and sinking back down from the surface, and – at least in some places – bathed in persistent underwater toxic plumes.

I remain extremely concerned about what has happened to the out-of-sight, underwater ecosystems of the Gulf of Mexico, especially at middle depths and on the bottom. These little known but ecologically vital elements of the ocean have been heavily exposed to oil-based pollution, both rising from the bottom and sinking back down from the surface, and – at least in some places – bathed in persistent underwater toxic plumes.

The total “dump” of highly toxic oil components, including low-molecular weight aromatic hydrocarbons (known familiarly as “BTEX” – benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and various xylenes), could have been up to 50,000,000 gallons. These are heavy-duty pollutants in their own right, including known carcinogens and reproductive toxicants, with a fair solubility in sea water. In a surface spill, pollution mostly evaporates, and the only real concern relates to emergency response workers that are exposed while on duty. In this underwater case, scientists simply do not know – yet – exactly how the massive load of pollution is being processed in the Gulf.

The total “dump” of highly toxic oil components, including low-molecular weight aromatic hydrocarbons (known familiarly as “BTEX” – benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and various xylenes), could have been up to 50,000,000 gallons. These are heavy-duty pollutants in their own right, including known carcinogens and reproductive toxicants, with a fair solubility in sea water. In a surface spill, pollution mostly evaporates, and the only real concern relates to emergency response workers that are exposed while on duty. In this underwater case, scientists simply do not know – yet – exactly how the massive load of pollution is being processed in the Gulf.