Science to Action: a ten-year review of California’s MPA Network

Marine protected areas (MPA) are a conservation tool that sets aside part of the ocean to protect it for long-term conservation, similar to the way a state or national park functions on land. These MPAs are an effective way to preserve biodiversity by protecting ecosystems. But how are they utilized by people, and do they support human engagement? And, while conservation alone is important, will MPAs build climate resilience?

With 124 MPAs, California has the world’s largest scientifically designed and functionally coherent network — a globally significant achievement — making it the perfect place to study both how humans interact with MPAs and the climate impacts of protected areas. After its design and inception from 2004-2012, a statewide monitoring effort began to assess the progress of the Network toward the goals of the California Marine Life Protection Act. Specifically, the achievements in protecting and conserving marine life, habitats, ecosystems and natural heritage while improving recreational, educational and study opportunities.

Every 10 years, California reviews the Network to inform the MPA Management Program and evaluate these advancements. The 2022 Decadal Management Review brought together MPA practitioners and managers, community stakeholders, tribal leaders and scientists to evaluate the entire statewide MPA Network for the first time across multiple habitat types for a range of users. A National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) Working Group, co-led by Jennifer Caselle and Kerry Nickols, was established to lead a synthesis science effort to contribute findings for the Review.

If you build it, they will come

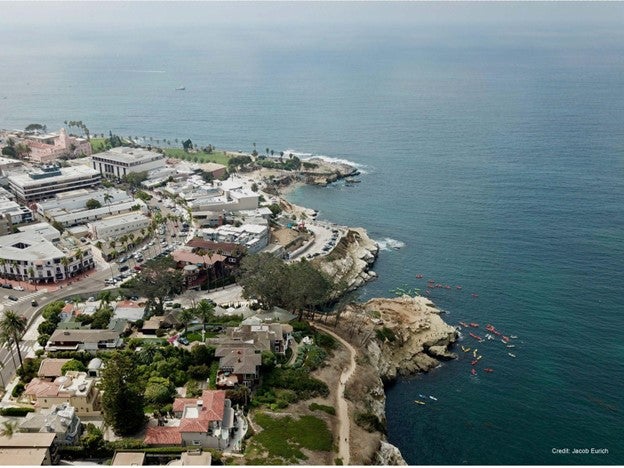

In a paper published in People and Nature, led by Christopher Free of the University of California, Santa Barbara, the NCEAS Working Group developed a framework for measuring recreational, educational, and scientific engagement across the California MPA Network. The study found high visitation and engagement in MPAs close to population centers, tourist destinations, state parks and sandy beaches.

Identifying conditions that promote or limit human engagement “ … is critical to designing MPA networks that achieve multiple goals effectively, equitably, and with minimal environmental impact,” said Free. “Human engagement can be promoted by developing land-based amenities that increase access to coastal MPAs. On the other hand, human engagement can be limited by locating MPAs in areas far from existing infrastructure. This choice depends on management goals.”

MPAs and climate resilience

During California’s MPA monitoring, the largest marine heatwave on record developed through the Pacific Ocean from 2014-2016. The extensive monitoring effort combined with the climate perturbation provided the NCEAS Working Group an opportunity to examine the ecological communities in the California Central Coast region’s protected areas before, during and after the heatwave.

In Central California, some ecological communities in MPAs experienced less change than in associated reference sites, but across all habitats monitored, there was no overarching effect of MPAs in mitigating change. The study, published in Global Change Biology led by Joshua Smith while he was a postdoctoral researcher at NCEAS, found that MPAs did not facilitate resistance or recovery within the studied timeframe. However, they were never designed to buffer the impacts of marine heatwaves.

“MPAs in California and around the world have many benefits, such as increased fish abundance, biomass and diversity, and even if they are being impacted by climate change, they are still being protected,” said Smith.

The study concludes that, ultimately, improved performance will “ … require integrating adaptive management with careful consideration of how abrupt climate change-driven perturbations may inhibit intended conservation outcomes.”

A path forward

The California Fish and Game Commission is currently reviewing the first Decadal Management Review of California’s groundbreaking MPA Network to decide how to direct CDFW and its partners to pursue recommendations outlined in the Review and identify the next steps to take for the management of the Network. Acknowledging how the public uses and engages with the Network and the impacts of climate change will improve the Network’s performance for the next decade. Guided by adaptive management, the State has the opportunity to evaluate progress to date, celebrate accomplishments and strengthen the MPA Network and Management Program going forward.

The NCEAS Working Group was generously funded by the California Ocean Protection Council (OPC, #C0752005) as part of the Decadal Management Review of California’s marine protected areas.

Free, C. M., Smith, J. G., Brun, J., Francis, T. B., Eurich, J. G., Claudet, J., Dugan, J. E., Gill, D., Hamilton, S. L., Kaschner, K., Lopazanski, C. J., Mouillot, D., Ziegler, S. L., Caselle, J. E., & Nickols, K. J. (2023). If you build it, they will come: coastal amenities facilitate human engagement in marine protected areas. People and Nature, 00, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10524

Smith, J. G., Free, C. M., Lopazanski, C., Brun, J., Anderson, C. R., Carr, M. H., Claudet, J., Dugan, J. E., Eurich, J. G., Francis, T. B., Hamilton, S. L., Mouillot, D., Raimondi, P. T., Starr, R. M., Ziegler, S. L., Nickols, K. J., & Caselle, J. E. (2023). A marine protected area network does not confer community structure resilience to a marine heatwave across coastal ecosystems. Global Change Biology, 29, 5634–5651. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16862