Let’s not turn back the clock on U.S. fisheries

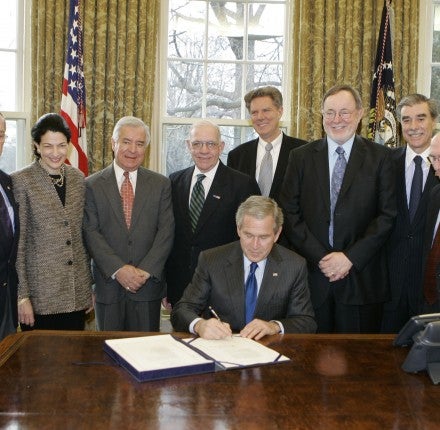

Photo Credit: AP, from talkingfish.org

Fisheries management can be a contentious business. So it’s all the more striking that the business of legislating on federal fisheries has historically been a relatively cordial affair. The gains of the last two decades have been possible because of strong cooperation across the aisle. In 1996 the Sustainable Fisheries Act (SFA) prioritized conservation in federal fisheries management for the first time. Alaska’s Republican Congressman Don Young jokes that the Magnuson-Stevens Act could have been called the Young-Studds Act because of his close collaboration on the SFA with Gerry Studds, then a Democrat from Massachusetts. It passed both chambers by overwhelming margins and was signed into law by President Clinton. Ten years later, the Magnuson-Stevens Reauthorization Act strengthened conservation mandates in response to continued overfishing and the failure to rebuild overfished species. It was championed in the Senate by Republican Ted Stevens in close cooperation with his Democratic counterpart Daniel Inouye. It cleared the Senate by unanimous consent, and was signed into law by President George W. Bush.

With Congress once again considering reauthorization of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA), there’s a welcome bipartisan consensus that the law is working. Senior lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are talking about building on our recent successes and exploring minor tweaks to the law rather than pursuing any kind of far-reaching rewrite. Despite serious ongoing challenges in specific fisheries, the legal framework created by Congress is clearly succeeding. Science-based annual catch limits are ending overfishing; and statutory rebuilding timelines have driven the recovery of more than 30 previously depleted stocks. This is great news for the health of the ocean. It’s even better news for seafood lovers, saltwater anglers, and coastal small businesses—the most important long-term beneficiaries of fishery management success.

In this context, a reauthorization discussion draft that has been circulated by House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Doc Hastings is all the more befuddling. Chairman Hastings voted for the 2006 reauthorization and celebrates its success. At a committee hearing convened to consider the discussion draft earlier this month he was emphatic: “In the [previous] hearings we’ve held there was general agreement that the Act is working,” the Chairman said in his opening statement. “I have said all along that the Act is fundamentally sound.” Yet as EDF outlines in a comment letter submitted to the committee today, the substance of the Chairman’s discussion draft is deeply discordant with his affirming rhetoric. His overhaul of the law would do more than merely “shift the balance” of fishery management in modest and benign ways. On the contrary, if enacted in its current form we fear it would set us on a path back to the failed management practices of the past.

Take overfishing. This scourge devastated many coastal communities in previous decades, costing countless jobs and forfeiting untold billions in lost economic output. During this month’s hearing, Chairman Hastings was careful to assert that his draft does not eliminate requirements to prevent overfishing, and in a narrow sense that’s true. Yet those provisions failed to prevent widespread overfishing until legislators added requirements for enforceable science-based quotas, which the discussion draft would undercut. It doesn’t take a fisheries scientist to see that rolling back those specific mandates will wind back the clock. Indeed, the discussion draft explicitly allows overfishing to continue after a population is declared overfished. And it permits catch limits set at the overfishing limit, inviting management on the knife’s edge.

Or take rebuilding. NOAA estimates that renewing depleted fish stocks will ultimately result in $31 billion in additional sales impacts, supporting 500,000 jobs and increasing dockside revenues by more than 50 percent. During this month’s hearing Chairman Hastings was quick to argue that his discussion draft does not eliminate the requirement that fisheries be rebuilt. But that assertion obscures the real story. As the testimony of NOAA Fisheries Deputy Assistant Administrator Sam Rauch made clear, managers struggled to rebuild depleted fisheries until the MSA imposed a statutory timeline, which has been the impetus necessary to do the hard work of rebuilding our nation’s fisheries. To do away with any meaningful rebuilding timeline, as the discussion draft proposes, would be a highly retrograde step.

At the same time, the draft threatens to stymie needed improvements. It could place obstacles in the way of wider use of electronic monitoring, which many see as the next step in reducing costs and improving data collection. It would limit the flexibility of many Councils to adopt new catch share programs—and it defines the term so broadly that it would include shifts in allocation. It would also expand state waters for the states bordering the Gulf of Mexico—but only for red snapper management, creating a confusing and unwieldy patchwork of regulations.

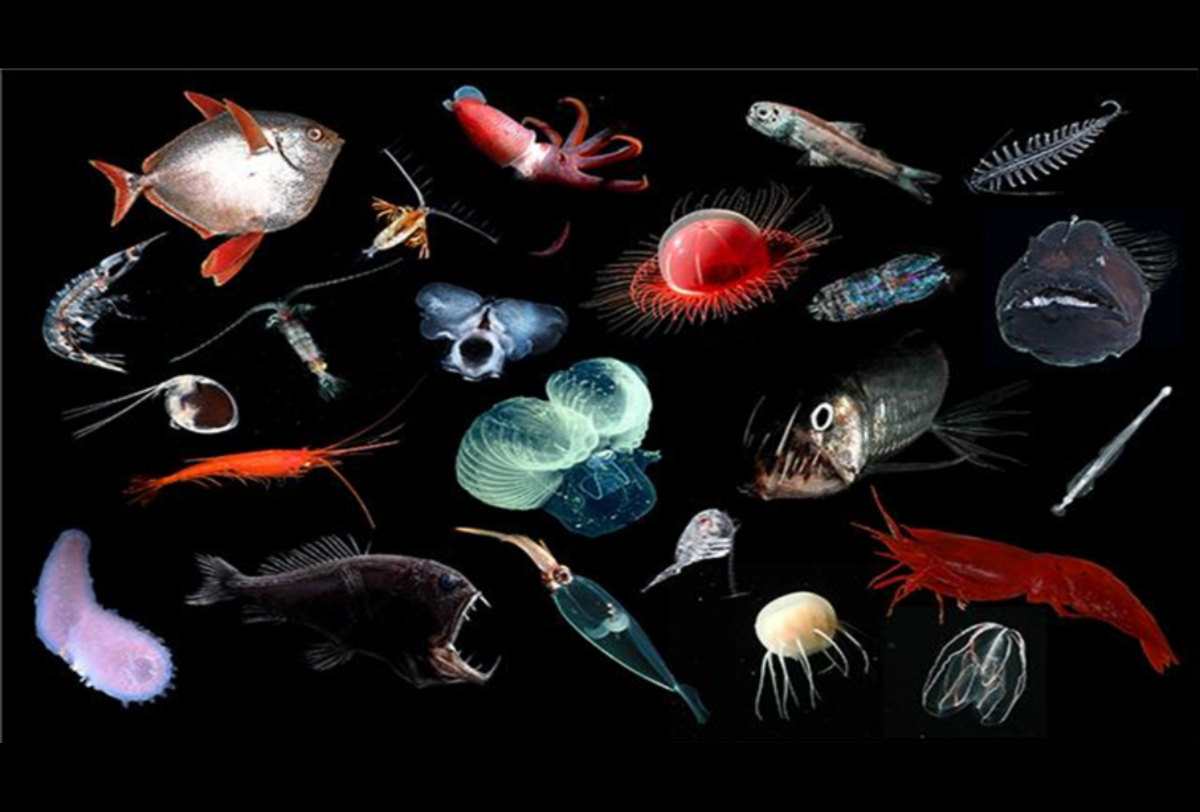

To be sure, challenges remain in federal fisheries. The scientific basis for establishing quotas and other management actions can and should be improved. Twenty-first century tools must be employed to assess species, and data from fishermen, academia, and other non-governmental sources must be integrated more effectively where possible. Costs of modern management threaten small boat operators in some areas. Conserving the ecosystem on which fisheries depend, rather than focusing on each species in a vacuum, could make our marine resources more resilient.

But addressing these challenges does not require rewriting the central provisions of the MSA. Improved implementation can address many of them, along with narrow revisions to the statute where the need has been shown to exist. EDF joined a diverse group of fishermen, other industry leaders, and academics in submitting a letter to Dr. Kathryn Sullivan, Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calling for more and better cooperative management of fishery resources. Congressman Wittman recently introduced H.R. 3063, which would make the stock assessment process more transparent and accessible to non-governmental participants without sacrificing conservation requirements.

The discussion draft, on the other hand, would make sweeping, disruptive and problematic changes to the MSA. The good news is that there’s still plenty of time for Congress to get reauthorization right. With the Senate moving closer to the release of its own discussion draft, there’s reason to hope that Chairman Mark Begich and Ranking Member Marco Rubio will forge a bipartisan approach that can emulate the traditions of their Senate predecessors. And with leaders in industry, government and academia all lining up to express concerns about the House discussion draft, there’s still the possibility that Chairman Hastings will consider wholesale changes to his reauthorization bill before it’s introduced. For the sake of fishermen, coastal communities and seafood lovers everywhere, we urge the Chairman to do just that.