New Study Shows That Catch Shares Meet Economic and Conservation Goals

Reprinted with permission from SeafoodNews.com

SEAFOOD.COM NEWS [seafoodnews.com] Jan 12, 2012 By Kate Bonzon

The following article was written by Kate Bonzon, who works for EDF and was one of the authors of a new scientific paper published in Marine Policy that analyzed the performance of 15 catch share programs in the US and Canada. She argues the data shows these programs met most of their goals, especially in the area of conservation, reduced discards, and increased revenue to harvesters. There was a shift in jobs from a larger number of part time jobs to a smaller number of full time jobs, which had varying social impacts depending on the fishery.

America’s fisheries, and the fishing communities they support, have struggled for decades to find a way to both rebuild depleted fish stocks and allow fishermen to earn a decent living. But it has become increasingly evident over the years that traditional management practices – such as drastically curtailing the fishing season – were failing to achieve either of these goals: fleets shrunk, revenues dropped, fishermen were often forced to put out to sea in bad weather, and the industry grew highly unstable. Fish stocks, meanwhile, continued to decline.

The latest effort to achieve that balance – a management approach known as “catch shares,” has generated much discussion among fisheries stakeholders over whether this approach is any better or worse than previous efforts. Now, a recent analysis of 15 fisheries in the United States and British Columbia published in the journal Marine Policy, provides data that clearly show significant environmental and economic improvements in fisheries that have made the transition to catch shares, an approach that allocates fishermen a share of the total allowable catch in exchange for making them accountable for staying within the catch limit.

The 15 fisheries, along with the year of catch shares implementation, are: mid-Atlantic surf clam / ocean quahog (SCOQ, 1990), British Columbia sablefish (1990), British Columbia halibut (1991), Alaska halibut (1995), Alaska sablefish (1995), Pacific whiting (1997), British Columbia groundfish trawl (1997), Alaska pollock (1999), Bering Sea and Aleutian Island King and Tanner crab (Alaska crab, 2005), Gulf of Alaska rockfish

(2007), Gulf of Mexico red snapper (2007), Atlantic sea scallop (2010), Gulf of Mexico grouper and tilefish (2010), mid-Atlantic tilefish (2010), Northeast multispecies groundfish (2010). The three BC fisheries are included in the analysis due to their interdependency and co-management with the Alaskan and Pacific coast catch share fisheries in the US.

Regardless of how some may feel about these management plans, catch shares, in short, are working.

The study analyzed trends from five years prior to the shift to catch shares until 5-10 years after the new system was put into place. The results? On average, fishermen are earning more; many fish stocks are recovering, often allowing regulators to increase catch limits; discards (the number of fish wasted because they are too small, caught inadvertently, or are not in season) have been greatly reduced; safety has dramatically improved; and the industry as a whole has stabilized.

Regardless of how some may feel about these management plans, catch shares, in short, are working. Consider the following:

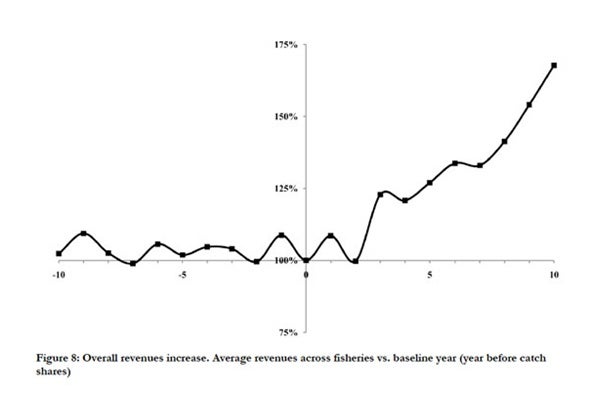

Under traditional management, as fishing seasons shrank to an average of 63 days – and in some cases to just a few days per year — fishing revenues had been steadily dropping. Under catch shares, fishing seasons increased to an average of 245 days. With more time to plan fishing trips to coincide with weather conditions and market demands and avoid causing a glut, fishermen operating under catch shares were able to nearly double revenues for individual vessels, on average. And fleetwide revenues also increased significantly.

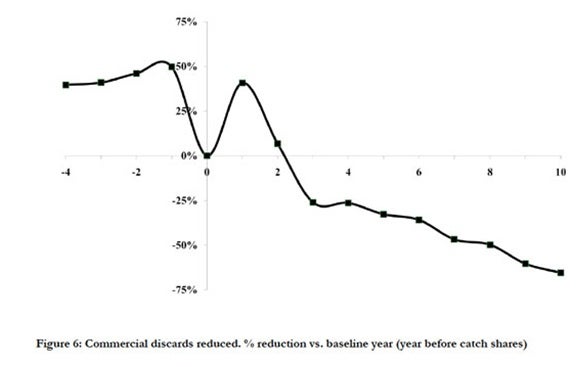

With no “race to fish,” fishermen are able to better select their fishing grounds, relocate their boats if they find themselves catching too many of the wrong species, and develop innovations in gear that allow them to fish more efficiently. All of this helps them to bring back more of the fish they want and less of what they don’t want: average discards have dropped a whopping 66 percent in the studied fisheries since the implementation of catch shares.

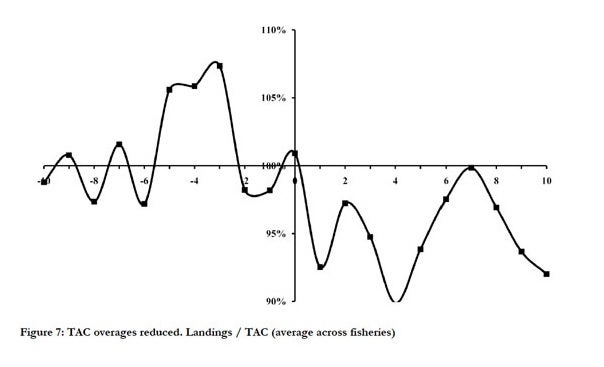

Under traditional management, the race to fish resulted in catch limits being exceeded roughly 50 percent of the time, and often by a lot. By comparison, once under catch shares catch limits were rarely exceeded, allowing fish stocks to rebound. This, in turn, provided a greater number of fish for all and greater scientific accuracy, which often allowed regulators to raise catch limits (which in turn helped to increase profits). In the 10-year period following the adoption of catch shares in the fisheries studied, catch limits rose an average of 19 percent.

With the freedom to wait out dangerous weather conditions and take the time for needed boat repairs, fishing safety has tripled under catch share management. Fewer accidents also mean fewer search and rescue missions by the Coast Guard, resulting in savings to taxpayers. In the Alaska halibut fishery alone, search and rescue missions dropped from 33 per year prior to catch shares to fewer than 10 per year under the new system.

Of course there are also costs to catch share management plans. The study found more-nuanced results when it came to social impacts. For example, while the total number of hours worked in the fishery increased slightly, there was a shift from many part-time job opportunities to fewer full-time jobs, a change that benefits some but not others. On the other hand, these jobs were more stable, safer, and better paid after catch shares were adopted.

Today, there are 16 federal catch share programs in six of eight fishery management regions, comprising half the value and three quarters of the volume of all federal landings. More fisheries are considering adoption of catch shares, such as the golden crab fishery in the South Atlantic. However, there is also a movement afoot by some in Congress to ban new catch share programs and cut funding for those already in place.

These efforts fail to take into account the data outlined in this report: namely, that catch shares – far better than the traditional management programs they have replaced – lead to substantial economic and environmental gains for both fisheries and fishermen. After years of struggling with failed fishery management systems, we now have one that works.