Cuban and Mexican researchers, Alejandra Briones and Ivan Mendez, look at a sample that will be analyzed in CIM’s lab to assess the faunal communities in the water column.

By: Kendra Karr and Valerie Miller

Part III of a blog series detailing a February 2013 Research Expedition in Cuba organized by EDF Oceans’ Cuba, Science, and Shark teams and funded by the Waitt Foundation. A team of scientists from Cuba, Mexico and the U.S. along with EDF staff set sail to share knowledge, scientific methodologies and to survey shark populations in Cuba. The tri-national expedition was led by Cuban scientists from University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research (CIM) and U.S. scientists from the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida.

Researchers from Cuba, Mexico and the U.S. participated in an exploratory research cruise in the Gulf of Batabanó along the Southern coast of Cuba to monitor shark populations, local faunal communities and to train fellow team members in monitoring techniques. Leaving the port of Batabanó, the RV Felipe Poeytransected the shallow, soft-sediment habitat that comprises the majority of the Gulf. The cruise set off for the remote and sparsely populated Isle of Youth, the largest island in the Canarreos Archipelago. Canarreos Archipelago is home to a national park and several marine protected areas (MPAs) which contain habitats that possess ecotourism potential and provide refuge for ecologically and economically important species such as lobsters, sharks and finfish.

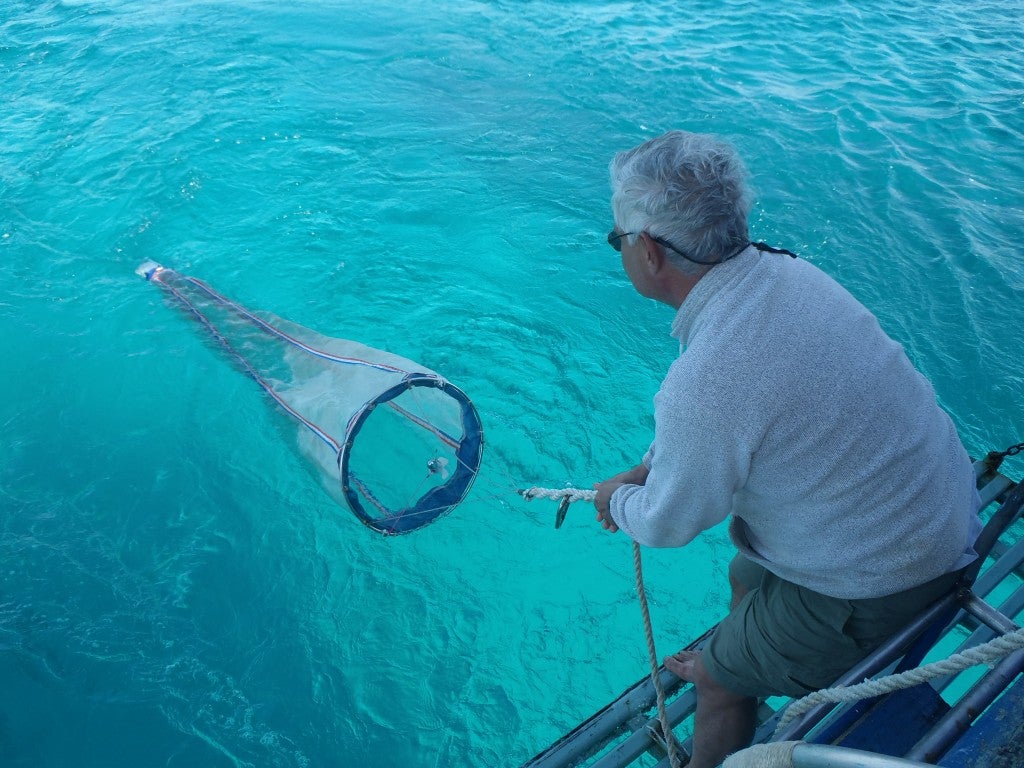

U.S. researcher Dr. Ernie Estevez collects the last sample of fauna from the water column outside the corals reefs of Punta Frances.

Monitoring activities started near the southwestern portion of the island, inside Siguanea Bay, continued around Punta Frances and into the nearshore waters facing the Caribbean Sea. This part of the Isle of Youth has a diverse array of habitats, including some of the healthiest and most intact coral reefs and mangroves in the region, as well as seagrass beds, and soft sediment habitats. Conducting a research expedition in multiple habitats presents a unique opportunity to observe organisms living at the bottom of the ocean (in benthic habitats) and in the water column surrounding these habitats. The expedition recruited two benthic researchers (scientists who study organisms living along the bottom of the ocean) to join the team comprised mainly of shark scientists, to capitalize on the opportunity and create a baseline monitoring program of these faunal communities across habitats in the Gulf Batabanó and surrounding waters. Dr. Ernie Estevez of the U.S. and Mote Marine Laboratory and Dr. Maickel Almanza of Cuba’s Center for Marine Research led the design of the monitoring program.

Monitoring programs help provide information about the health of the area prior to future impacts (i.e. disturbance either natural or human caused), so that analysis can aid forecasting. Baseline data helps measure the severity of ecosystem disruptions and helps to calibrate recovery programs. Additionally, this data may help identify areas that are more resistant, or less resilient to disturbances over time. Long term monitoring of ecological communities and populations is one of the most effective tools that managers and scientist have to track and analyze how ecosystems work. Unfortunately, long-term datasets are rare and those that do exist are often limited in geographic scope.

What’s a faunal community and why are they important?

The team identified plankton living in the water column and macrobenthos (small fish, crustaceans, worms and mollusks living at the bottom of the ocean) across habitats as targets because changes in the diversity and abundance of these fauna can be indicators to the health of the ecosystem, and they are critical components of important fisheries in the Gulf of Mexico. The small fish, crustaceans, worms and mollusks that comprise the fauna collected in the monitoring program are often the principal food source for fish in the region. Sharks, as apex predators, depend on highly productive foraging areas (e.g., dense seagrass meadows) and support abundant amounts of prey, such as larger fish that consume plankton. The team also recorded environmental variables necessary for a healthy habitat, including temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, depth and organic content in sediments. Absent baseline species and ecosystem data, future efforts to end overfishing, protect marine life and improve the management of marine resources will not succeed. This is just one of the ways in which Cuba, Mexico and the U.S. are working together to improve monitoring efforts that will increase data availability and enable a tri-national assessment of shark population status, including an understanding of how variability in abundance of faunal communities and their predators influence foraging behavior and shark migration in the Gulf of Mexico.