Establishing a biological and ecological baseline of Cuba’s coastal ecosystems

By: Kendra Karr & Owen Liu

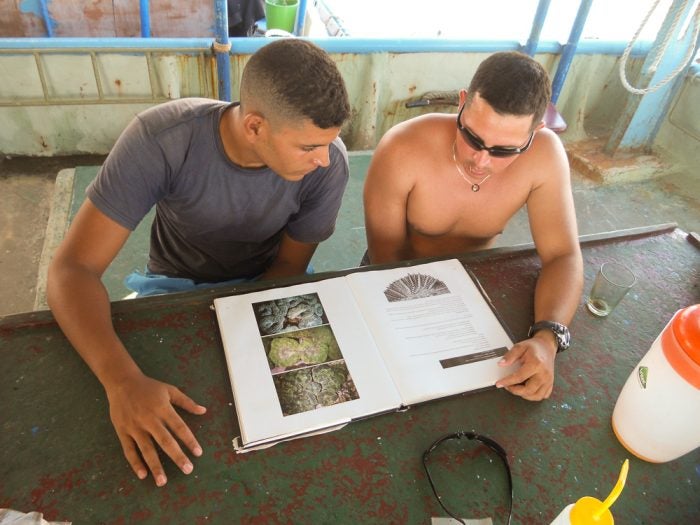

A team of scientists from Cuba and EDF set sail on an expedition to assess the status and health of marine ecosystems of the Gulf of Ana Maria and the Gardens of the Queen marine reserve in southern Cuba, one of the most pristine and intact coral reef ecosystems in the Caribbean.

One morning we awoke to a small tuna boat pulling up alongside the RV Felipe Poey. The crew of the “Unidad ‘77” had been targeting bonito, a small tuna-like fish, south of the Gardens of the Queen marine reserve. EDF scientists were eager to tap into the captain’s localized knowledge, and peppered him with questions that were ably translated by CIM’s Patricia González. The captain described his fishing grounds, proudly displayed his catch and explained how his crew times their trips to coincide with certain phases of the moon. Before shoving off, the captain asked for some cooking oil for his next voyage. We traded oil for tuna and enjoyed fresh fish for many meals over the next few days.

A Scientific Baseline for Management:

Vessels like Unidad ‘77 are common in Cuba: small boats that work for the state, the livelihoods of their crews dependent upon a stable resource base. This and future expeditions will synthesize scientific findings to inform the management of Cuba’s marine resources. While our voyage was one of discovery, there were practical benefits too; the datasets we initiated will ultimately increase understanding of how ecosystems in Cuba work, which is essential to developing its coastal fishing economy in a sustainable manner.

Long-term monitoring programs are some of the most powerful tools that managers and scientists have to track and gauge ecosystem performance, variation and resilience. They generate baseline information about the status of a target species or ecosystem. In many cases, baseline information is used to analyze an impacted region after a major change (such as a disturbance either natural or human produced), or as reference data to compare between areas of interest; for example, to compare Cuba to other regions of the Caribbean that have been heavily impacted. Well-designed programs aid in evaluating impacts and help tailor recovery and management strategies. Additionally, long term monitoring data helps to identify areas that are more or less resilient to change over time. We can identify factors that enhance ecosystem health and resilience, as well as factors that have negative impacts.

But long-term fishery datasets are rare, and of those that exist, most are limited in their geographic scope. The data collected during this expedition and future trips represent a significant step forward for Cuba. Additional trips are planned in other regions of the country, alongside annual sampling across all of the monitoring regions including the Gardens of the Queen.

Data for Sustainable Fisheries Management:

Like Unidad 77’s crew, fishermen across Cuba rely upon on finite marine resources to survive. Better management, fortified by sound science, is essential to sustain livelihoods from the sea. These jobs are a critical component in any coastal nation’s economy. Unfortunately, across the Caribbean and in Cuba, commercially valuable fish stocks are in jeopardy. By better understanding fish populations, EDF can assist Cuban scientists, managers and fishermen in developing science-based recommendations for sustainable fishery management policies, such as cooperatives and other catch shares.

To inform management efforts, fishery data and fishery models are used to generate stock assessments which can provide estimates of the current population size of species, rate of fishing, time trends, and optimum levels of population size and harvest rates. In addition, the existing fishery dependent data can be used in combination with the fishery independent monitoring to provide stronger stock projections. Our October expedition focused on using fishery independent visual surveys, and began developing a fishery dependent monitoring program using beach seine. Combining both fishery independent and dependent monitoring enables a full view of the assemblage of fish that would otherwise be difficult to sample without the use of fishing gear — for example, fish that exist in shallow, sandy nearshore habitats.

Balancing Livelihoods and Conservation:

The same day we met the crew of Unidad ’77, two CIEC researchers returned to Felipe Poey toting 10 newly hatched green sea turtles they removed from the beach of Cayo Caballones in the Gardens of the Queen. Releasing the turtles over the shallow seagrass beds where the Felipe Poey had anchored would help them avoid predation by iguanas and seabirds that roam on their natal beach.

After spending the day endlessly counting fish and filling in reams of data sheets, the turtles were a welcome reminder of why we do the work we do.

The Gardens of the Queen and Gulf of Ana Maria are a unique ecosystem, a mosaic of dense mangrove forests, bordered by extensive seagrass meadows and beautiful coral reefs. The Gulf and the Gardens exhibit a delicate balance between humans and marine organisms that depend on the same resources. A bonito fisherman’s livelihood depends on a healthy, resilient ecosystem just as much as a newborn green turtle does.

We watched as the young turtles made their way into their new surroundings, cautiously venturing into the underwater world of the Gardens of the Queen. They are entering a world undergoing change, as Cuba rapidly develops and opens gradually to increased tourism, even in remote places like the Gardens. With our October expedition, scientists from EDF, CIM, and CIEC planted the seeds for continued collaboration and the creation of a robust scientific monitoring program for Cuba’s coastal ecosystems and fisheries. The baseline of biological and ecological knowledge formulated from expeditions like ours, and those planned for the future, will help ensure that fishermen and marine species alike can continue to coexist in a prosperous ecosystem.