All who enjoy the wild biodiversity of the seas should take a moment this week to mark the passing of Dr. Bill Ballantine, the Founding Father of what has become a fast-growing global network of marine protected areas.

The science of setting aside unique sanctuaries from development is an art that dates back centuries – at least on land. America’s own federally designated national parks, wildlife refuges, and forest reserves can be traced to the mid-1800s.

But ocean protection is a relatively recent phenomenon, emerging only in the late 1970s. And it’s arguably more difficult to know how to chart, value and protect life that is hidden from view.

No one had previously envisioned what marine reserves would look like, where they should be, or how they might work. Then Bill showed us all exactly how it could be done, and done well.

He helped enact New Zealand’s Marine Reserve Act in 1971, fought six years of political opposition to create the country’s initial marine reserve at Leigh Marine Laboratory – one of the first “no-take” reserves in the world – followed by another 13 reserves encircling what he referred to as “the most maritime country in the world” consisting of 90 per cent ocean. When he died, a dozen more marine reserves were underway.

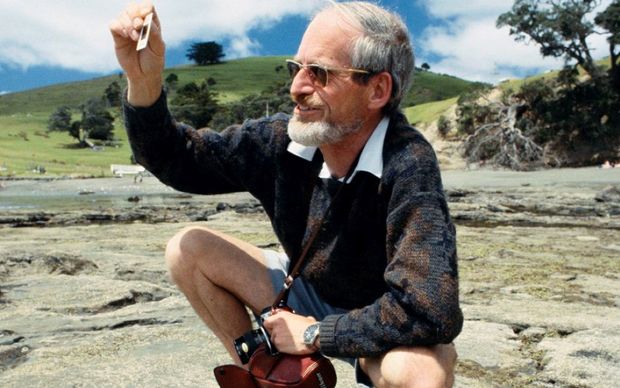

It is hard for EDF to overstate the extent of his impact on our own work. We invited him to give a series of talks, which shaped our approach in the early days of MPA maturation in the U.S. It was serious business, and he had to be driven to what could be lengthy meetings. But along the way he found time and energy to teach my 3-year-old daughter – a next generation ocean steward –songs about fish. Bill could play as hard as he worked; on his last celebratory visit to the U.S. he left a big bottle of Ballantine’s whiskey, still in my office.

Bill stressed how beautiful, incomparable places deserve our respect and formal recognition as a whole. And that required a profoundly different way to think about the integrity of natural world rather than individual species, whales or fishing rights.

He also showed us how high-powered science could help us understand the vital role these places play in the sea. Bill led the front end of an entirely new research discipline of designing reserves in the ocean, where there are no boundaries, and thus a pressing need to understand spatial, structural, and ecological connectivity.

Anyone who spent time with him sensed his impatience, linked to his passion and drive. Others found him grumpy and opinionated. Yet he knew, early on, that actually securing a marine reserve required far more than just knowing what to protect, where and why. He had deep respect for the essential role of local people in understanding the richness and vitality in their surrounding waters, of having a bona fide partnership with coastal communities and fishermen in order to make it endure. And of keeping protected areas open for people to explore, photograph, research, understand, love, and fight for.

Almost everything we have done to advance ocean protections and marine protected areas were built on the back of Bill’s formative experience in New Zealand.

So while I mourn his passing, I also plan break out that bottle of Ballantine’s he left me, and toast his legacy, which will live on in the seas that surround us all.

One Comment

May the effort and vision of legendary Bill out live the “ballantine”. May his challenges and successes be an encouragement to us who are opposed daily by reckless fishers who continue to thwart all efforts in designating “no take”zones especially in my country around the Gulf of Guinea.