By Maria Doa, PhD, Senior Director, Chemicals Policy, Maricel Maffini, PhD, Consultant, and Liora Fiksel, Project Manager, Healthy Communities

What happened

You may have seen news or online content from FDA about chemicals in our foods, including that our food – and everything else in the world – is made up of chemicals.

FDA’s online content also characterizes toxic chemicals such as lead and mercury simply as naturally occurring or naturally present in our environment. It further fails to distinguish the most harmful chemicals by asserting that for all chemicals, it is the amount of the chemical that matters when determining their harm.

Why it matters

It is true that everything, including our food, is made up of chemicals. However, that does not mean that we should treat all chemicals equally.

Highly toxic chemicals such as lead, mercury, PFAS, TCE, methylene chloride, and BPA are examples of substances that should not be in our food. These toxic metals and synthetic chemicals do not have nutritional benefits and are not equivalent to the chemicals that make up the proteins, fats and carbohydrates that are necessary for a healthy diet. We should not be exposed to toxic chemicals at any level.

The suggestion that toxic metals and synthetic chemicals such as PFAS in our food are just chemicals like essential elements such as potassium in bananas is misleading and harmful.

Unfortunately, FDA accomplished just that. In a webpage released earlier last week, the agency tried to address worries about chemicals in food, an issue that consumers have been concerned about for several years. In its attempt to bring confidence about the safety of the food supply, FDA tried to normalize the presence of toxic chemicals, including neurotoxicants, carcinogens and endocrine disruptors, in our food.

Our take

If a toxic chemical such as lead or mercury is naturally occurring, is it OK?

No. While there are very low levels of these metals that are naturally present in our environment the majority of what is now in our environment is not natural background but the result of pollution and other contamination due to human activities. These levels are not “naturally occurring.”

It is also essential to recognize that naturally occurring does not equate with safety. There is no safe level of exposure to lead and mercury which are potent neurotoxicants. They are particularly harmful to infants and small children and exposure to even small amounts can cause harm.

Is there always a safe level of exposure to a chemical?

Treating all chemicals in our food the same way ignores the science. Some chemicals, in addition to lead and mercury, are so toxic that essentially any amount of exposure is of concern:

- Chemicals like TCE associated with multiple types of cancers and harm pregnant women and infants.

- Chemicals like PFAS also known as forever chemicals because they are so difficult to destroy that can harm pregnant women, cause cancer and harm the immune system in vanishing small quantities. For two of the PFAS, EPA just declared that there is no safe level of exposure.

- Chemicals like BPA that harm the immune and reproductive systems, disrupts the normal function of hormones and affects learning and memory at levels 20,000 times lower than previously estimated, and

- Chemicals like methylene chloride are associated with cancer and liver toxicity.

- Chemicals like phthalates that also disrupt the normal function of hormones specially during development of the male reproductive tract. These chemicals are strictly limited in children’s toys due to their toxicity.

And being exposed to more than one of these chemicals that cause the same harm, such as cancer, can increase the harmful effects.

Further, Congress also recognized that some chemicals should not be allowed to be added to our food. Period. Congress included a provision known as the Delaney Clause in our food safety laws that states a food additive cannot be deemed “safe if it is found to induce cancer when ingested by man or animal.” Yet unfortunately, some carcinogens continue to be allowed.

How can we be assured of a safe food supply if the agency that is supposed to ensure safety takes the same “it’s the amount that matters” approach to these toxic chemicals as it does to salt?

And how can we have confidence that FDA will fully consider consumers in determining food safety when the agency not only falsely equates toxic chemicals with the chemicals that make up the proteins, fats and carbohydrates in our diet but also takes a patronizing approach to the public by stating that “chemical names may sound complicated but that does not mean they are not safe.”

Next steps

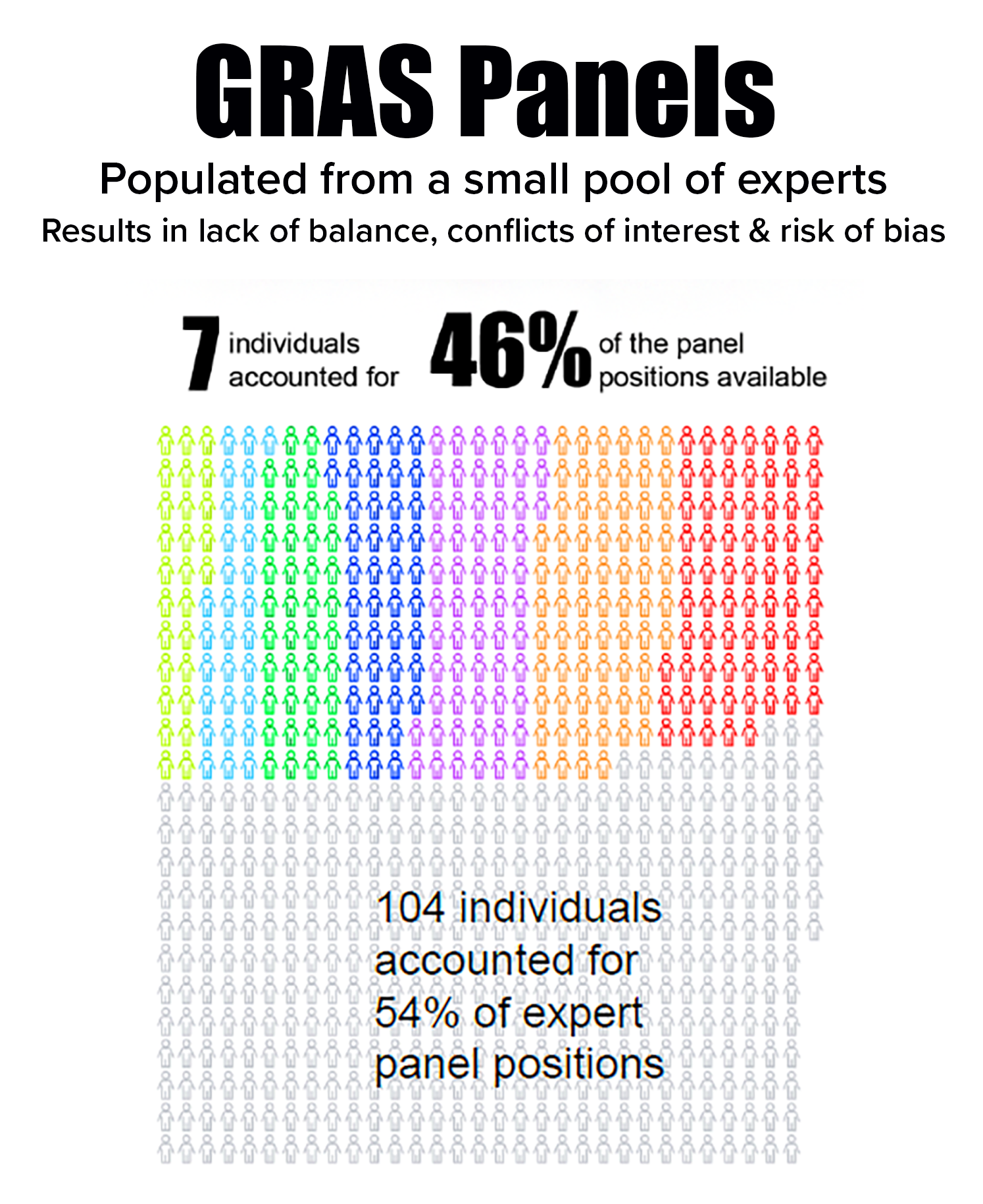

In the last several years, public interest organizations have petitioned FDA to review the safety of chemicals known to pose risk to health. Many petitions are still unresolved.

FDA should recognize toxic chemicals for what they are – chemicals that can harm our health and well-being – rather than camouflage them just as any other chemical. The science and the law demand that in making decisions about food safety, FDA recognize and act on the most toxic chemicals and fully consider consumers in its decision making.