What happened

The Good Food Foundation recently announced its annual awards recognizing foods with both superior taste and responsible business practices, sparking controversy when a plant-based blue ‘cheese’ product was initially a finalist in the cheese category, then was disqualified and removed from the list of finalists. According to the foundation, the product was disqualified because one of the ingredients, kokum butter, had not been designated as GRAS (generally recognized as safe) by the Food and Drug Administration.

Why it matters

Kokum butter is derived from the seeds of a kokum tree’s fruit, primarily cultivated in India. The substance is not found in any of FDA’s lists of ingredients either approved or reviewed for safety. Someone somewhere determined that the use of kokum butter in food is GRAS. However, who made that determination, when, and the basis for the decision are unknown. For example, how much of it is safe to eat? Is it safe for anyone—children, pregnant women, people with preexisting conditions? Could it cause allergic reactions or interfere with medication? Does it leave the body quickly? Does it mimic or interfere with hormones? We just don’t know and neither does FDA.

Here’s a quick overview of the GRAS system, which we have written about extensively in our Broken GRAS blogs.

- “General recognition” means that a safety assessment was performed and published, and the scientific community agrees that use in food is safe;

- GRAS substances are exempted from pre-market approval by FDA;

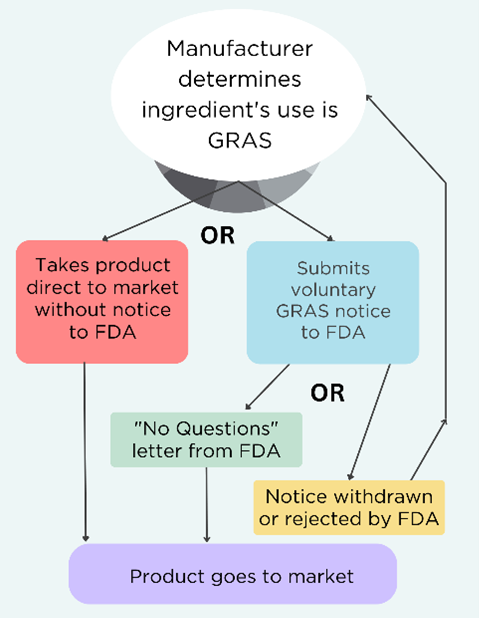

- FDA has interpreted the law as allowing manufacturers to independently determine the use of a substance is GRAS without informing the agency;

- FDA created a voluntary program for manufacturers to submit their chemical’s safety determination in the form of a GRAS notice to the agency for review;

- Manufacturers can withdraw the request for review at any time and still claim their product is GRAS. See the decision tree below.

Our Take

Back in 2022, tara flour, another ingredient of unknown safety, caused more than 400 people to get sick. Like kokum butter, tara flour was not approved or reviewed for safety by FDA.

We applaud the Good Food Foundation for requiring that the ingredients used in foods competing for its awards be reviewed by FDA. It is a matter of protecting public health. We fully support, at minimum, company submissions of GRAS notifications and FDA reviews. Although we have been critical of FDA’s outdated science in safety assessment of chemicals, these notifications provide at least some degree of visibility into the food supply that otherwise is not available to the agency in charge of protecting the public.

Next steps

We will continue to engage with FDA to ensure the agency has the tools and resources to strengthen the oversight of companies making GRAS claims without disclosing their safety assessments. The ongoing reorganization of FDA and creation of the Human Food Program is a unique opportunity to fix the broken GRAS program so that all Americans can have confidence in the safety of the food they eat.