Unlocking the black box of agricultural supply chains

The corn supply chain is a complex, ever-changing, and often unpredictable system. Measuring the environmental impacts of grain production can be just as complex and daunting – especially with thousands of players involved.

Understanding corn’s environmental footprint is fundamental to generating solutions that help farmers improve efficiencies and reduce fertilizer losses and hold companies accountable for meeting and measuring the success of their sustainability goals.

That’s why EDF partnered with the University of Minnesota’s Northstar Initiative for Sustainable Enterprise to develop a feed grain transport model that estimates emissions from grain farming. Northstar is a program within the university’s Institute on the Environment, which has deep expertise in the complex agricultural supply chain and is able to connect the dots between products on the shelves and their environmental impacts. As I’ve blogged before, EDF believes this kind of increased transparency is good for consumers and businesses themselves.

I asked Jennifer Schmitt, Ph.D, lead scientist of the NorthStar initiative, to elaborate on the team’s research and on the importance of data collection and measurement in agriculture.

Why the focus on agricultural supply chains?

Companies increasingly are concerned with the environmental impacts of their supply chains. Suppliers and end users commonly make up over 75 percent of the carbon and water impacts for a company, and in agricultural-based industries, supply chains are the source of other environmental concerns, such as nutrient runoff, pesticide use and biodiversity loss.

These impacts pose significant risks to companies downstream from farm fields through reputational harm, climate disruptions to agricultural supplies and the possibility of regulatory action. Given this, increased transparency in agricultural supply chains makes good business sense.

How are you navigating such a complex topic?

As you note, tracing supply chains is difficult. Even the most well-meaning companies find that navigating and tracing their vast network of suppliers is daunting. Companies, industry groups and environmental organizations need research-based tools that illuminate the black box of agricultural supply chains. That means incorporating a wide array of data around supply chains and environmental impacts to facilitate improved management of operational and reputational risks. Making progress in this area can also provide new business opportunities. It isn’t just about risk.

We’re working to identify, characterize and quantify the environmental impacts of U.S. agricultural supply chains through a spatial and company supply chain perspective.

How did you become involved with EDF?

EDF initially reached out to us with a key question for its work: where do the largest beef, pork and poultry companies buy their corn in the U.S.? The goal was to reduce the environmental impact of corn farming – and a key part of this effort is to focus on feed grains, which represent nearly 40 percent of all the corn acreage in the U.S. The first step in the process was to understand the sourcing regions from which companies purchase the corn for animal feed.

Since that initial conversation, we’ve worked together to evaluate agricultural supply chains more broadly, linking the environmental impacts of corn farming to specific supply chains, and to develop a feed grain transport model.

What does the feed grain transport model measure?

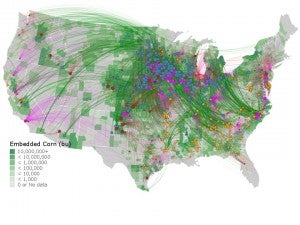

The Northstar team has developed a data platform and a multi-stage supply chain transport model showing how corn and soy travel through the farm-to-feed-to-food pipeline in the U.S.

The model, which uses publically available data, tracks corn and soy supplies from county-level crop production to county-level crop consumption, including feedlots and grower farms. It accounts for virtually all corn demand in the U.S. The model then estimates the additional movement of animals and their embedded feed grains to primary processing facilities. These facilities are connected to companies, making it possible to estimate the spatial sourcing of crops by meat producers.

What will the model mean for sustainable agriculture?

Linking the movement of corn from farms to processing facilities makes it possible to connect the environmental impacts associated with crop production to industries, corporate supply chains, and facilities. For each of these units our model determines the “feed shed” (i.e. feed sourcing areas) and estimates the carbon and irrigation impacts associated with the feed shed. We are currently working to include other environmental impacts such as water depletion, nutrient run off, etc.

The more we as researchers, practitioners and companies themselves know about corporate agricultural supply chains, the better equipped we are to identify opportunities for increasing sustainability to scale.

Jennifer Schmitt, Ph.D.

jenniferschmitt@umn.edu

@JenSchmitt618

Related:

Animal feed is at the heart of grain sustainability >>

Meet the young Smithfield agronomist who’s turning the feed grain industry on its head >>