New Case Study: Collaboration was Key in NYC Clean Heat Success

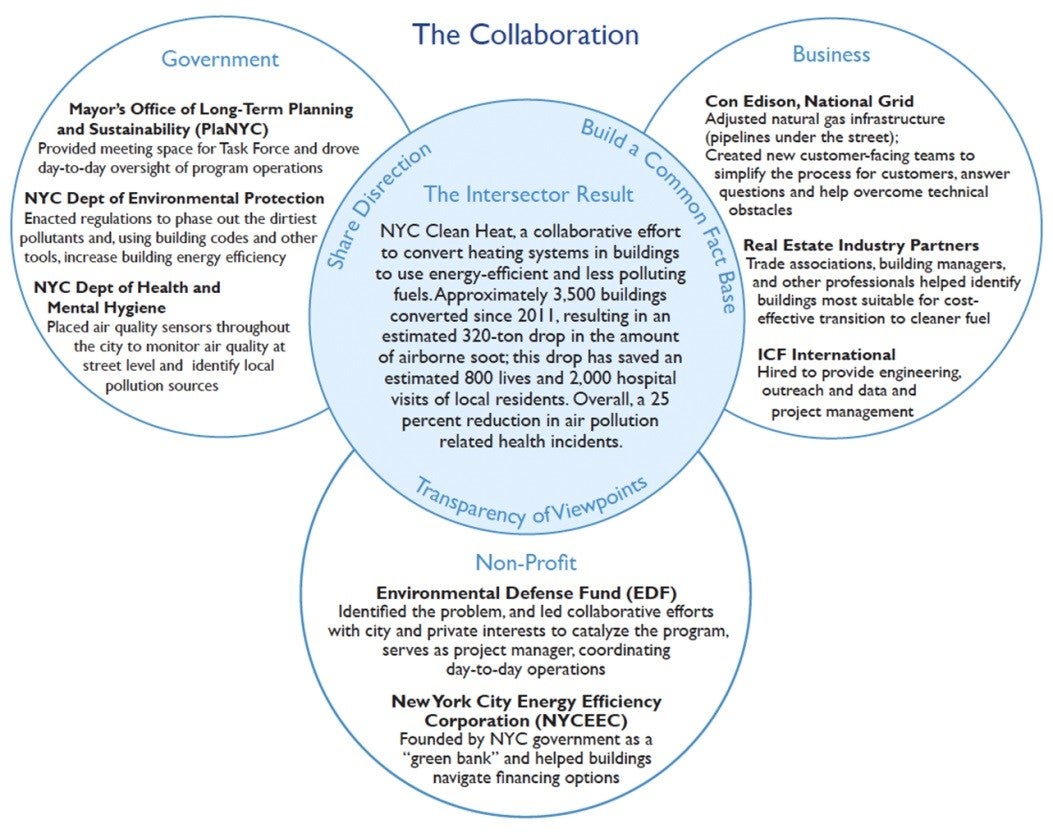

Recently, EDF and The Intersector Project teamed up to create a case study on the NYC Clean Heat program, a collaborative effort that included partners from private real estate interests, New York City, oil companies, and the Environmental Defense Fund. The program began in 2007 to improve the city’s air quality and the case study highlights the inter-workings of this cross-sector collaboration that has made NYC Clean Heat such a success.

The NYC Clean Heat project achieved success by transitioning over 3,300 buildings off of No. 6 and No. 4 oil (used to heat residential and commercial buildings in the winter), removing more than 300 tons of soot (PM2.5) from the air New Yorkers breathe. As a result, from 2011 to 2012, New York City was ranked number four for the cleanest air in the nation.

EDF was thrilled to work with the Intersector Project, a non-profit “conducting research in intersector collaboration, and conveying the findings to leaders in every sector to help them design and implement their own effective collaborative initiatives,” on this case study. They spotlight a model that we believes works: by bringing all the right people to the table (government, business, finance, non-profits, and more) and taking an inclusive approach, programs are most effective. NYC Clean Heat has clearly demonstrated this, so we were happy to have the opportunity to show how it works.

Broken up into five parts – The Story, The Collaboration, The Leadership, The Toolkit, and The Intersector Result – the case study aims to uncover what made this unique partnership such a success. Ideally, other big cities interested in improving air quality through energy use modifications will use this case study as a model to replicate New York’s success.

Some of the key takeaways outlined in the case study include:

- Approximately 3,500 buildings converted since 2011, resulting in an estimated 320-ton drop in the amount of airborne soot; this drop has saved an estimated 800 lives and 2,000 hospital visits of local residents. Overall, a 25 percent reduction in air pollution related health incidents.

- Andy Darrell and others at EDF provided leadership to catalyze the program, and recognized the opportunity for a partnership with the City of New York.

- Collaboration across diverse sectors can provide successful, long-term program results.

We hope that the NYC Clean Heat model can continue to be used in New York City to tackle broader issues, such as building-wide energy efficiency and energy affordability. We also feel that the NYC Clean Heat model can be used in other cities to tackle similar issues. For example, the city of White Plains, NY is in the process of proposing legislation similar to what is currently in place in New York City, phasing out the use of heavy heating oil. They and other cities looking to de-carbonize their energy use should look to this case study as a guide.

5 Comments

Well, there is indeed the short term benefit of removing soot from the air, but the overall program is a financial and environmental disaster of the first order, and certainly does not deserve to be duplicated anywhere.

Simply put, this program has led and does inevitably lead to capital destruction on a vast scale, for little or no environmental benefit, except in the short term, and limited to the local environment:

– Fuel switching from #6 and #4 to natgas or #2 seemed like a good idea at the time, but it really diverted the attention from the economic feasibility of directly switching thousands of buildings to a renewable infrastructure, and have a much greater and long term environmental impact. We presented this to NYC here:

– Clearly now that we understand that the systemic losses of methane in effect effect the environmental advantages of natural gas, it is clear that while locally some soot was removed, the overall impact is neutral, and again, a direct switch to renewable infrastructure would have been more effective.

– The massive switch to natural gas has disastrously undermined the city’s resiliency, by making nearly the entire city dependent on a single fuel. Oil-fired buildings, as much as buildings with substantial renewable infrastructure, enhance the survivability of the City in case of any serious gas disruptions. Citizens also are paying for it massively with increased electricity. The retail rate from ConEdison in January 2012 was 7 cents/kWh, in 2013 it was about 14 cents/kWh, and in 2014 it was 22 cents/kWh. So citizens are paying through the nose for this single fuel lunacy, as heat is now competing with electricity, and the traditionally lower rates for electricity in winter are a thing of the past.

– Eventually, buildings will have to switch to renewable infrastructure any way, for there is no way to survive in this city with window A/C if by 2050 we’ll have 3 times the number of 90+ degree days in summer, so central solar thermal HVAC is the way to go. This could have been undertaken in lieu of the simplistic fuel switching of PlaNYC, and reduced GHG’s by 50-90% instead of not at all, or slightly if more efficient burners were used.

– As a first step in most apartment buildings either solar thermal or geothermal DHW would eliminate 30-50% of fossil fuel use permanently.

For further analysis of NYC Clean Heat, see here:

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment on this blog post. Our primary concern with NYC Clean Heat is improving the public health in the city by helping buildings convert from the heavily-polluting No. 6 and No. 4 oils to cleaner fuels. Not every building can go straight to renewable sources of energy, though many have chosen to go the extra mile and incorporate it. Our team finds the solutions that work for each building to help them comply with the regulation phasing out No. 6 and No. 4 oils, and has converted over 3,500 buildings to a cleaner alternative. These buildings were among the worst polluters and addressing them first vastly improved air quality. Of the conversions, roughly 75% have converted to the cleanest possible fuels, cutting pollution to the lowest levels in over 50 years.

I do not doubt the good intentions of this program. And undeniably in the near term, and in the local area the switch from #6 and #4 oil to nat gas, seemed to solve a problem, until you understand that natural gas overall is actually as bad or worse for clean air, if you look system wide. Once you understand that, and you understand that while the switch to renewables, partial or complete may not be an option in all buildings, the overall effect of switching to renewables would be far greater, and would be permanent. It obviously was never seriously studied, an oversight that resulted in capital destruction from pursuing a small incremental, and largely cosmetic improvement, in lieu of a long-term structural solution, which moreover would result in a permanent improvement of building values. In buildings that are suitable to make such conversions it is relatively easily feasible to achieve 50-80% reductions in their total carbon footprint, in place of typically may be 15-25% under the fuel switching scenario. So, in spite of all the self-congratulatory press we’ve seen, I remain convinced that on proper analysis, the program booked no appreciable results, and very likely was regressive in the long run.

Thank you for your opinion. We appreciate all feedback.

You’re welcome. I may add that besides anything else, the switch to renewable infrastructure would vastly reduce the single biggest source of indoor air pollution, being fossil fuel combustion. So the focus on the local elimination of some outdoor airpollution, while foregoing the opportunity of the very urgent indoor airpollution problem, is really to miss the larger part of the opportunity in respect of clean air as well.