Sam Lovell, Project Manager.

Any successful initiative to replace lead service lines (LSLs) – the lead pipes connecting the water main under the street to homes – must be built on clear and consistent communications to residents. This will not only accelerate LSL replacement progress and equip people with information that impacts their health – it will also help build trust.

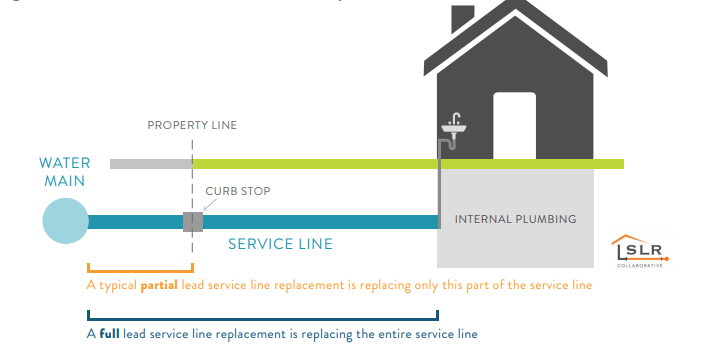

Many residents likely don’t even know what an LSL is, let alone that they need to take proactive steps if they want it fully replaced. In most communities, ownership of the water service line is split between the drinking water utility and the resident. Fully replacing an LSL entails removing the portions of lead pipe both on public and on private property. A partial replacement (when only one of the sides of an LSL is removed – see image below) is an issue because it can spike lead levels in the short-term and does not have the long-term benefit of reduced lead exposure seen with a full LSL replacement.

When describing LSLs and the replacement process, water systems must explain whether they are referring to the full LSL or only one of the sides, and the implications of this for the resident.

A case of misleading communication

Over the summer, we saw how easy it is to miss the nuance of service line ownership when the utility Louisville Water announced that it, “removed all its known lead service lines that deliver drinking water, a milestone that only a few water utilities in the United States have achieved.” What the announcement did not make clear is that the utility did not complete full LSL replacement on both public and private property. Only several paragraphs further down did the announcement clarify, “Customers are responsible for the water lines on their property and a small percentage have a lead line that goes into their home.”

Article from WHAS 11.

Many local news outlets covered the announcement. And, as is not unexpected given the wording in the announcement, the articles missed the fact that there are still Louisville residents with LSLs. We realized this problem because a WHAS 11 article about the announcement mentioned EDF’s tracking of the communities across the country that have fully replaced LSLs (see screenshot to the right). The eight communities referenced in the article’s subtitle have replaced all known LSLs on both public and private property, something Louisville Water has not done.

This is an issue because readers of the articles – many of whom may be Louisville Water customers looking for local news, would likely come away with the false impression that all lead pipes have been replaced where they live. And that simply is not the case. Those who actually go to the water utility’s website and the announcement to learn more would likely assume exactly what the news reporters did.

We reached out to Louisville Water to share our concerns about the utility’s messaging. A representative emphasized that the utility has been working to inform customers about the presence of LSLs on private property and described a new pilot program to provide funding to assist with the cost of replacement. These are important steps – and we have highlighted Louisville on our webpage recognizing LSL replacement efforts. However, that does not change the fact that the water utility has not yet reached the milestone of full LSL replacement, and – because of its confusing announcement – many local news outlets ran stories that could mislead residents.

We also reached out to WHAS 11 to ask that they clarify their article, which they have since done (see the online version for the updates)[1].

Not an isolated problem

We noticed a similar issue in 2018, when the California Water Board posted results of its statewide LSL inventory in an interactive map and failed to explain that the inventory only covers the part of the service line on public property. The press release for the map was particularly concerning as it stated, “The good news is that we only have four water systems that report having lead lines,” and “many systems are entirely lead-free.” It is easy to imagine a resident taking these statements to mean that lead pipes are not an issue in their community – when that may not be the case.

We raised our concerns with the California Water Board, and it has since added a webpage providing more background for residents on the issue and an update to its map explaining that the inventory does not cover the service line on private property. It should be noted that LSLs are not as prevalent in California as in water systems in the Midwest, Mid-Atlantic, and New England. See our blog for more.

Clarity is particularly important for maps

Interactive maps that provide information about LSLs are valuable tools to engage residents and to accelerate LSL replacement. We recommend that communities in the process of refining LSL inventories consider developing and publicizing the information in such a format.

However, as the California example makes clear, if a map only includes the service line material on the public side, it must be clear about this distinction and explain that it does not have information about the material on private property. Though as a best practice, such tools should include information about the material on both the public and private sides of the line. EDF has confirmed that this is preferable for users, as well. In a peer-reviewed study of different mapping and search tools used by the three largest cities in Ohio, we found that users were frustrated when they learned a tool only provided information about one side of the line.

Expected requirements should prompt action

EPA’s draft Lead and Copper Rule revisions include several new communication requirements. Among other provisions, beginning in 2024, the proposal would require water systems to notify consumers annually if they have an LSL and to describe the health effects of lead and ways to reduce exposure. A similar notice would be required if the service line is of unknown material that may be lead. In addition, customers would need to be notified if the LSL is disturbed, such as during infrastructure work or restoring the service. Though not yet final, these requirements should prompt water utilities to ensure all of their communications are clear and consistent.

Getting the word out to get the lead out

While consumers can always reach out to their water utility with questions about lead in the water system, they have many competing priorities. To avoid confusion and misunderstandings up front, we urge water utilities to recognize and prevent mistakes by clearly communicating to residents and other customers – including schools, child care facilities, and businesses – the status of both portions of service lines and what the community is doing to replace them.

Everyone deserves to know whether they have a lead pipe providing water to their home and to have the opportunity to remove that source of lead exposure to protect themselves and their families.

[1] WHAS 11 removed “other” from the article’s subtitle (“only eight other U.S. cities have fully removed lead service lines”) and added an ending paragraph describing why partial LSL replacements are a problem on July 18.