ASDWA releases useful guidance to help states develop lead service line inventories

Tom Neltner, J.D., Chemicals Policy Director and Lindsay McCormick, Program Manager

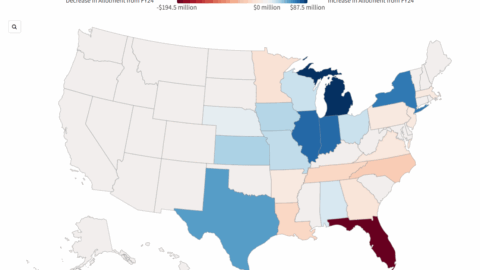

As we have explained in past blogs, it is critical that states have rough estimates of how many lead service lines (LSLs) each drinking water utility in the state may have in order to develop sound policy decisions and set priorities. Congress recognized the importance of LSL inventories when it directed the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 to develop a national count of LSLs on public and private property in the next round of the 2020 Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey. States have a crucial supporting role in the Needs Survey since it is the basis of allocating State Revolving Loan Funds to the states.

This month, the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators (ASDWA) released a useful guidance document to help states develop LSL inventories. The guidance builds on the lessons learned from:

- Mandatory surveys conducted by California, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin;

- Voluntary surveys conducted by Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Washington; and

- Responses to requests for updated Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) service line preliminary materials inventories conducted by Alabama, Louisiana, Kansas and Texas.

Summary of ASDWA’s guidance

ASDWA’s guidance provides different recommendations for states that already require community water systems (CWSs) to submit annual reports and those that do not.

- States with existing annual reporting: The guidance encourages states to include “counts of service lines grouped by each type of materials commonly used,” in their annual reporting requirements that CWSs submit. The guidance provides a table summarizing the categories of service line materials identified by the four states with mandatory reporting.

- States without annual reporting: The guidance encourages states to conduct an initial voluntary survey “to assess the situation and develop more useful estimates than may already be available.” While the information won’t be complete, it should be better than the rough state estimates reported by the American Water Works Association (AWWA) in a 2016 report. The results from Indiana’s and Washington’s voluntary surveys suggest that, with good follow-up, as much as 90% of a state’s service lines could be identified through voluntary reporting. Where states have barriers to conducting voluntary surveys, they may want to partner with the state AWWA section.

Key considerations for the survey content:

- Cover all commonly used materials: To provide a more complete assessment, surveys should request counts of all types of materials commonly used in addition to lead. The guidance includes tables showing the types of service line materials identified by the four states with mandatory reporting, including links to those state’s resources. Common material types include galvanized steel, copper with lead solder, unlined cast iron, and four types of plastic.

- Reporting “unknowns:” Surveys should allow for reporting on unknowns especially in initial or preliminary efforts. Unknowns should be divided into two categories: “unknown – likely contains lead” and “unknown – likely does NOT contain lead.” This approach enables states to track progress in reducing number of service lines with unknown materials. In addition, being explicit about unknowns provides a more realistic, transparent assessment of the state’s expected needs and serves as an incentive for CWSs to reduce the number of unknowns.

- Public vs. private property: The reporting should include estimates for all service lines, whether on public or private property, and include whether the customer or the utility owns the different portions of the line and the legal basis for that determination.

Key considerations for survey design and implementation:

- Two-stage mandatory reporting: When a state does not have existing annual reporting, it should consider requiring a two-stage reporting process beginning with a preliminary materials inventory followed by a comprehensive inventory a few years later. The approach expands on the existing requirement in the LCR from the 1990s that requires a preliminary inventory sufficient to define water sampling programs and a comprehensive one when a utility exceeds the lead action level.

- Phasing in reporting requirements: States could phase-in the inventory reporting by: 1) focusing on CWSs that are preparing to begin their periodic cycle of lead in drinking water monitoring; 2) starting with large and medium CWSs that likely have stronger asset management programs; or 3) expecting bi- or tri-annual reporting to reduce burden on the state and CWSs.

- Work with CWSs: States undertaking a survey should provide clear guidance to CWSs to ensure more useful and consistent data. They should draw from resources already developed by other states. They should also following up with CWSs that fail to report and analyze the information to identify potential reporting errors and inconsistencies.

- Make reports publicly available: States should make the information for each CWS and all reports publicly available in a user-friendly, online portal and develop reports summarizing the information. Being transparent upfront builds public confidence and reduces the burden of responding to requests for the information.

Conclusion:

We applaud ASDWA for releasing a guidance to help states move forward with the important step of developing an accurate inventory of LSLs in their state. The guidance provides useful and timely information for states. We encourage states to move quickly with their own efforts. We also recommend that CWSs review the guidance to develop their own inventories so they can more easily respond to state requests and develop and accelerate LSL replacement in their communities.