The ongoing leak at the Aliso Canyon natural gas facility owned by Southern California Gas has driven more than 2,000 families from their homes in the Porter Ranch area of Los Angeles and prompted Gov. Brown to declare a state of emergency. It’s dumped an estimated 83 thousand metric tons of methane into the atmosphere so far (see our leak counter here), with no clear end in sight.

The ongoing leak at the Aliso Canyon natural gas facility owned by Southern California Gas has driven more than 2,000 families from their homes in the Porter Ranch area of Los Angeles and prompted Gov. Brown to declare a state of emergency. It’s dumped an estimated 83 thousand metric tons of methane into the atmosphere so far (see our leak counter here), with no clear end in sight.

But what are the next steps from here? What are the wider implications of this continuing disaster; and where else could something like this happen? What do we do to prevent another Aliso, and how will Southern California make up for the environmental damages once the leak stops?

The troubling fact is that Aliso Canyon is just the tip of a very big iceberg, reflecting both the industry’s widespread methane problem, and the potential local risks of over 400 other storage facilities nationwide. It spotlights a longstanding, largely invisible problem, promising to shift political dynamics around solutions. And the penalty phase, when it comes, will hopefully codify important principles that will also have a big effect on industry behavior.

The Invisible Crisis Unfolding Every Day

For starters, Aliso Canyon is a particularly egregious example of a problem that’s happening every day across the country. Right now, methane is leaking at every stage of the oil and gas supply chain, from thousands of wellheads to the miles of local utility lines under our streets.

Most leaks aren’t as big as Aliso Canyon, but they add up to over 7 million tons of methane emissions a year – the same 20-year climate impact as 160 coal-fired power plants. You can’t see it, and in many cases you can’t smell it (the noxious smell driving residents from Porter Ranch is added by utilities as a way of enabling you to know when there is a gas leak in your home). But leaks of various amounts are happening every day at tens of thousands of oil and gas facilities nationwide.

EDF and others have done extensive research showing the extent of the problem; where it’s coming from; and ways to fix it. In fact studies released in just the past few months have shown the problem is much bigger than EPA estimates. Unfortunately, the oil and gas industry is fighting new state and federal policies that would improve inspection and maintenance, and reduce these leaks.

Aliso Canyon will undoubtedly force state and federal policymakers, the industry, investors, and others to take a much harder look at these systemic problems.

Can it Happen in MY Backyard, Too?

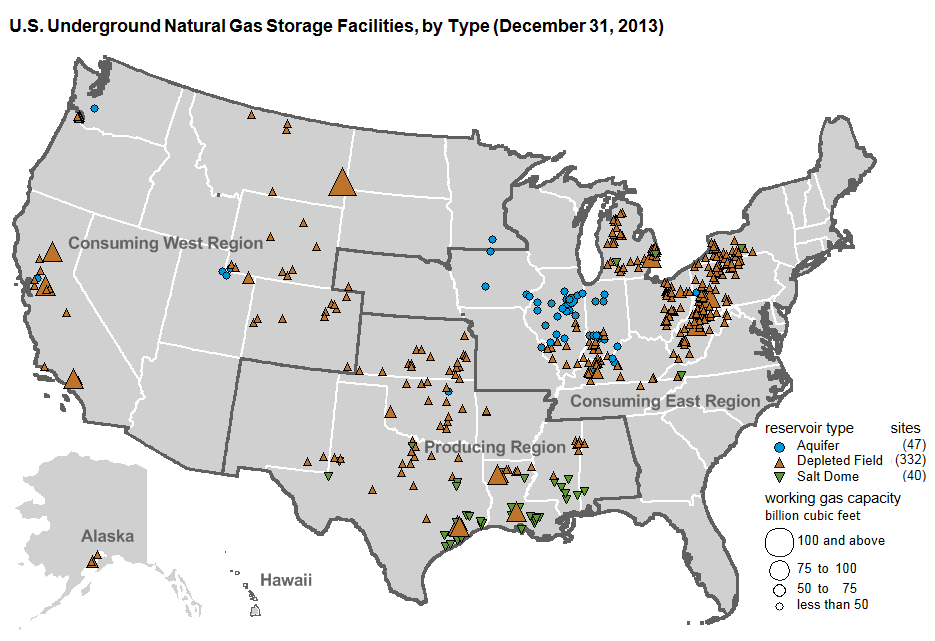

Storage facilities like Aliso Canyon aren’t just a California problem, either. There are about 400 natural gas storage sites like it across the country.

Generally, the safety and environmental integrity of gas storage facilities are regulated at the state level. While a significant subset of these facilities is subject to federal jurisdiction, current federal rules generally say nothing about the operation and maintenance of these sites, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency is only now beginning to take steps to regulate methane pollution from pipes and compressors that serve them.

These facilities have mostly flown under the radar. Fortunately, there are some quick ways to start addressing this. EPA has the legal ability to require systematic leak detection and repair of much of the equipment at facilities like Aliso Canyon – along with hundreds of thousands of other wells around the country.

States can also improve their storage well integrity efforts in order to reduce the likelihood of catastrophic failures in the first place. Well integrity oversight requires addressing permitting, construction, operation, maintenance, repair, and closure requirements. And the U.S. Department of Transportation, which is charged with overseeing the safe operation of the nation’s oil and gas pipelines and associated infrastructure, can also play a role here.

Standing in the Way of Solutions

Sadly, industry is fighting new national policies that would require oil and gas companies to use basic, low-cost methods to find and repair leaks. Their trade associations acknowledge there’s a problem, but want to be left alone to fix it voluntarily. But all the evidence says that simply won’t work.

That’s why we need national standards to ensure it happens. That includes rigorous leak detection and repair requirements that apply to all sources – those already in existence and the ones that will be built in the future.

Paying the Price, Repairing the Damage from Aliso Canyon

Obviously the top priority now is to stop the Aliso Canyon leak. Governor Brown’s new order declaring the leak a state of emergency should ensure the right mix of resources is brought to bear so that this happens as quickly as possible. But we also need to be thinking about how the utility will address the environmental damage that’s been done, and how we can prevent leaks like this in the future.

Besides stronger regulatory safeguards for the oil and gas industry, we need to look at the demand for natural gas, which is why utilities like SoCal Gas need to store so much gas in the first place. In addition to stronger regulations of gas facilities and operations, it is also sensible to look at how we can reduce dependence on natural gas. California is particularly dependent on gas generation to meet sharp spikes in peak demand; if we can shave even a little off that load, it means less need for Aliso and other gas storage facilities and gas pipelines.

Company Must Fix the Damage

Another key question is how the company plans to repair the damage to the environment. They can’t just write a check and walk away. While the leak is ongoing, it’s impossible to know the full extent of the damage that needs to be compensated. But it’s clear that three things are going to have to happen before we can put this accident behind us:

First, the local community needs to be fully compensated for the damages they’ve suffered.

Second, the environment, and particularly the climate deserves full compensation, with specific focus on reducing oil and gas methane emissions beginning with eliminating methane locally and more generally in the Los Angeles basin where the accident took place.

Third, both the company and the state need to implement regulations and policies targeted at preventing something like this from ever happening again, which also includes measures to reduce the region’s dependence on natural gas, particularly peak gas demand, which is what necessitates facilities like Aliso Canyon in the first place.

One thing we know for sure is that the final emissions tally is going to be enormous – so far equal to burning almost 800 million gallons of gasoline (you can check the latest count here). The company responsible for the mess needs to be held responsible for cleaning it up, and we not only need to make the community and climate whole, we need to start down a path of a meaningful transition away from peak gas dependence.

Image Source: Energy Information Administration

2 Comments

Mark, indeed “there are some quick ways to start addressing this”. A few which top the list:

– EDF needs to put the pieces of the puzzle together after they fight to close carbon-free nuclear plants (San Onofre) and they are replaced shortly thereafter by twice as much natural gas capacity. And the utilities which close them are selling themselves the natural gas they burn.

– EDF needs to stop promoting “carbon capture and storage”, the fossil fuel industry’s morning-after pill for continuing to destroy the earth’s climate, when polluters like Sempra Energy can’t even successfully store their carbon before it’s burned.

– EDF needs to stop pretending there’s anything environmental about magnifying fears of carbon-free nuclear energy in order to raise $100 million from their anti-nuclear base each year.

There’s a common thread here.

If we hadn’t fumbled JFK’s ball, we’d not hove this and we’d not have about a trillion tons of CO2 floating around.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzoW_cVg2hE (talk)

https://attachment.fbsbx.com/file_download.php?id=1681093738816758&eid=ASu9veYdBw3ZjqfjaYuTMz7Y0VOut01p8qeqEWyzcOduUzfbU8VB1CIk0RKBA6WTBTY&inline=1&ext=1453080959&hash=AStXY_cIuvdNu2aL