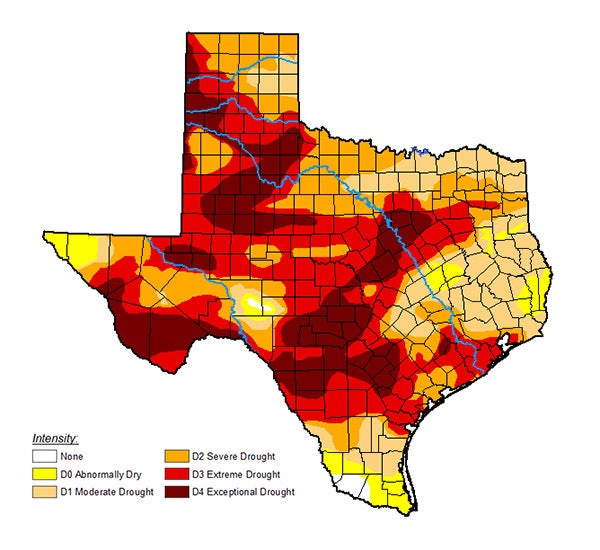

It is obvious to any Texan that we are in a horrific drought. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, more than 80% of Texas has been facing drought conditions most of the year. Extreme or worse drought now covers 51% of the state.

It is obvious to any Texan that we are in a horrific drought. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, more than 80% of Texas has been facing drought conditions most of the year. Extreme or worse drought now covers 51% of the state.

The drought is hurting water supplies, particularly in Central Texas, which has received as little as 5 inches of rain since October in some areas, well below average. Coleman County had its driest January-to-June period on record going back to 1895.

Groundwater functions as a buffer to streams and rivers during periods of low rainfall, sustaining vital baseflow and spring flow. But increased groundwater pumping coupled with a prolonged decrease in aquifer recharge from little rainfall causes the connection between rivers and groundwater to be lost and rivers and springs to dry up.

Although it will rain again, the reality is that Texas is becoming more arid. In the future, we will see less rain and more days of triple-digit temperatures. As Texas weather changes, so must our methods of managing groundwater, which will become increasingly precious.

Flows in streams and springs are plummeting.

Stream flows across the Hill Country, where most of the state’s rivers begin as headwater springs, are historically low. The Frio River at Concan is on track for its lowest annual stream flow since 1956. Inflows from tributaries to the Highland Lakes, the drinking water source for the Austin area, have essentially ceased, with many streamflow gauges across the Hill Country registering zero flow. The Lower Colorado River Authority has halted water deliveries to farmers downstream.

San Marcos Springs, which is among one of the largest springs in the Edwards Aquifer, is flowing 80 cubic feet per second below historic average. Las Moras Springs in Kinney County, which discharges an average of about 12 to 14 million gallons, per day has stopped flowing. Jacob’s Well in Hays County, which usually offers visitors a respite from the summer heat, has stopped flowing and is closed for swimming.

Groundwater wells in the Trinity Aquifer in Hays County are approaching historical lows. The Edwards Aquifer, the primary source of drinking water for millions of Central Texans, is at its lowest level since 2014.

Planning for a dryer Texas requires investing in groundwater.

With more severe drought and population growth in Texas, managing groundwater in a balanced, proactive and sustainable way is crucial to safeguard property rights and rural economies and protect our iconic rivers and streams.

Groundwater provides over 60% of the state’s overall water and sustains on average 30% of the water flowing in our rivers. In rural areas, groundwater is the sole source of water for many communities, landowners and agriculture. These communities’ futures depend on sustaining groundwater resources.

Texas should start by dedicating more funding to effective groundwater management and planning. Texas has spent billions of dollars on water infrastructure. But the state provides little funding for groundwater conservation districts (GCDs) to develop local data, such as installing groundwater monitoring wells, or to develop local models to understand how to manage unique hydrogeologic conditions, address local impacts or ensure they have sufficient groundwater supplies in the future to sustain local communities.

The state also provides millions of dollars to support the regional water planning and state flood planning process, which are both bottom-up, locally driven processes. But the state provides no financial support to groundwater conservation districts, which are expected to develop long-term groundwater availability goals that are essential to state water planning. This is an unfunded mandate, with the state getting a free ride on the backs of groundwater conservation districts who must take on the costs of developing data, planning and reporting on their own, often with limited resources.

Accurate data and modeling are critical for GCDs to develop local strategies to protect property rights and sustain groundwater levels, regional economies and ecosystems. While groundwater is appropriately managed at the local level, the state has a responsibility to ensure that groundwater conservation districts have technical resources and data to effectively manage it.

As we experience worsening drought and rivers and streams shrink, Texas can ensure these natural resources and the communities that rely on them don’t dry up. We need a Texas solution to the state’s groundwater challenges — one rooted in the wisdom and service of local leaders supported by state funding — to preserve the state’s economy, its natural resources, and the lives and livelihoods of our people.