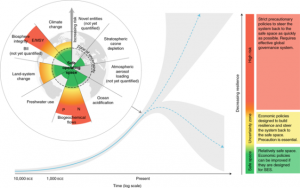

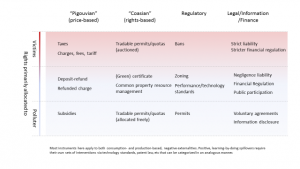

This is part two of a five-part series exploring “Policy Design for the Anthropocene,” based on a recent Nature Sustainability Perspective. The first post explored the intersection of policy and politics in the development of instruments to help humans and systems adapt to the changing planet.

A recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) working paper made headlines by revealing that the world is subsidizing fossil fuels to the tune of $5 trillion a year. Every one of these dollars is a step backward for the climate. That much is clear.

Instead of subsidizing fossil emissions, each ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted should be appropriately priced. That’s also where it’s important to dig into the numbers.

It’s tempting to go with the $5 trillion figure, as it suggests a simple remedy: remove the subsidies. At one level, that is precisely the right message. But the details matter, and they go well beyond the semantics of what it means to subsidize something.

Direct subsidies are large

The actual, direct subsidies—money flowing directly from governments to fossil fuel companies and users—are “only” around $300 billion per year. That is still a huge number, and it may well be an underestimate at that. The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2014, which took a closer look at fossil subsidies than reports since, put the number closer to around $500 billion; a 2015 World Bank paper provided more detailed methodologies and a range of between $500 billion and $2 trillion.

What all these estimates have in common is that they stick to a tight definition of a subsidy:

Subsidy (noun, \ ˈsəb-sə-dē \)

“a grant by a government to a private person or company to assist an enterprise deemed advantageous to the public,” per Merriam-Webster.

These taxpayer-funded giveaways are not only not “advantageous to the public,” they also ignore the enormous now-socialized costs each ton of CO2 emitted causes over its lifetime in the atmosphere. (Each ton emitted today stays in the atmosphere for dozens to hundreds of years.)

The direct subsidies also come in various shapes and forms—from some countries keeping the cost of gasoline artificially low, to a $1 billion tax credit for “refined coal” in the United States.

Indirect subsidies are significantly larger

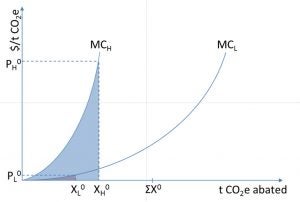

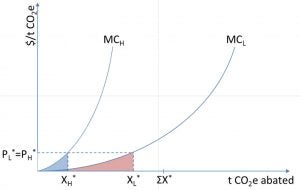

The vast majority of the IMF’s total $5 trillion figure is the unpriced socialized cost of each ton of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere. Each ton, the IMF estimates conservatively, causes about $40 in damages over its lifetime in today’s dollars.

Depending on one’s definition of a subsidy, this may well qualify. It’s a grant from the public to fossil fuel producers and users—something the public pays for in lives, livelihoods and other unpriced consequences of unmitigated climate change.

The remedy here is very different than removing direct government subsidies. It’s to price each ton of CO2 emitted for less to be emitted. The principle couldn’t be simpler: “When something costs more, people buy less of it,” as Bill Nye imbued memorably on John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight recently.

https://twitter.com/GernotWagner/status/1128444583229186048

All that goes well beyond semantics of what it means to subsidize. One policy is to remove a tax loophole or another kind of subsidy, the other is to introduce a carbon price. The politics here are very different.

Unpriced climate risks might be much larger still

The $5 trillion figure also hides something else. By using a $40-per-ton figure, the IMF focuses on a point estimate for each ton of CO2 emitted, and a conservative one at that. The number comes from an estimate produced by President Obama’s Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Carbon. That’s a good starting point, certainly a better one than the current Administration’s estimate.

But even the $40 figure is conservative. It captures what was quantifiable and quantified at the time. It does not account for many known yet still-to-be-quantified damages. It does not account for risks and uncertainties, the vast majority of which would push the number significantly higher still.

In short, the $5 trillion figure may well convey a false sense of certainty.

In some sense, little of that matters. The point is: there is a vast thumb on the scale pushing the world economy toward fossil fuels, the exact opposite of what should be done to ensure a stable climate.

In another very real sense, the different matters a lot: Politics may trump all else, but policy design matters, too.

By now the task is so steep that it’s simply not enough to say we need to price emissions and leave things at that. Yes, we need to price carbon, but we also need to subsidize cleaner alternatives—in the true sense of what it means to subsidize: to do so for the benefit of the public. Whether that comes under the heading of a “Green New Deal” or not, it is a much more comprehensive approach than one single policy instrument.

This is party 2 of a 5-part series exploring policy solutions outlined in broad terms in “Policy Design for the Anthropocene.” Part 3 will focus on “Coasian” rights-based instruments, taking a closer look at tools that limit overall pollution to create markets where there were none before.