This blog was authored by Environmental Defense Fund economist Luis Fernández Intriago and Universidad de Los Andes professors Jorge García López and Julián Gómez Gil.

The saying “Nothing about us without us” is widely used among Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities to emphasize the importance of involving them in policies that govern their territories and communities. The expression serves as a call to action, highlighting that those affected by specific issues should be included in making policy decisions around them.

However, policymakers and researchers consistently decide on policy design and construct models without consulting and considering the opinion of the affected communities and key stakeholders. Efforts to stop deforestation are a clear example of this: new policies go into place without any input from communities that rely on forests for their livelihoods, cultures, or basic survival. These local and Indigenous communities are an untapped source of wisdom, leadership, and capacity to support efforts to conserve rainforests.

To remediate this, Environmental Defense Fund, Universidad de Los Andes, and the Centro de Estudios Manuel Ramírez, right since the beginning of the project, started an engagement process in Colombia to demonstrate how engaging key local and Indigenous stakeholders could lead to better policy design to protect forests in the country.

Why Colombia?

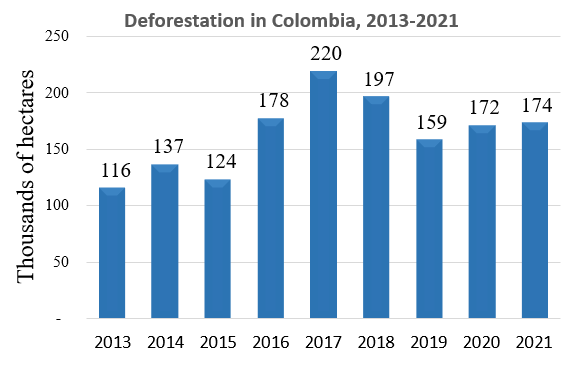

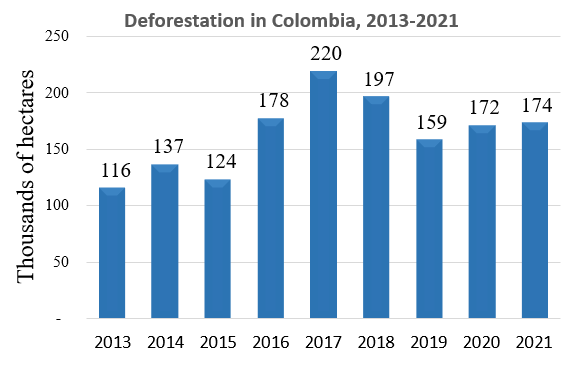

Colombia faces enormous challenges with deforestation: 184,000 hectares per year of natural forests were destroyed between 2017 and 2021. Deforestation accounts for 33% of the country’s total climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, halting deforestation is critical for achieving the country’s Paris Agreement commitments (called “Nationally Determined Contribution” or NDC).

As in many other countries, the AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land-use) sector is not subject to regulations in Colombia. However, this presents an excellent opportunity for the Colombian government to leverage private finance from national sources—such as through the upcoming Colombian Emissions Trading System[1] , which must be implemented by 2030—and international sources —such as the LEAF Coalition— using jurisdictional REDD+ (JREDD+) crediting. JREDD+ programs extend the REDD+ framework for sustainable forest management and conservation by addressing deforestation at the regional or ‘jurisdictional’ level—protecting forests across wide regions instead of plot-by-plot and even resources.

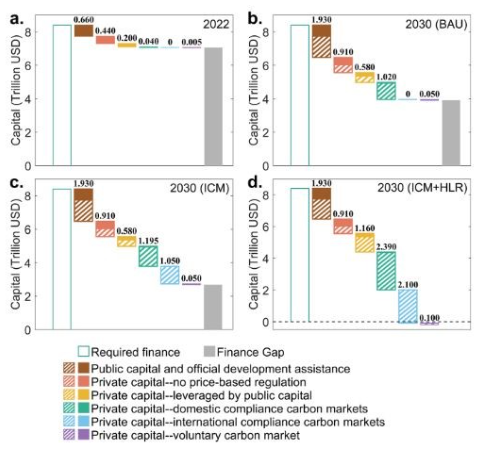

Climate mitigation is now a top priority for many individuals, governments, and corporations, creating strong demand for ways to stop deforestation in tropical forest countries in high-integrity ways rapidly. Our research finds that government funding required to reduce deforestation levels consistent with Colombia’s NDC could drop from $900 to $75 million when national and international private finance is harnessed.

The Study

Our study aimed to identify inclusive, equitable ways to include JREDD+ in Colombia’s climate mitigation policies. We established three parallel and interconnected pillars: first, we focused on engagement with primary stakeholders. Second, we constructed a model to illustrate how JREDD+ may help Colombia meet its NDC target cost-effectively while benefiting local communities. Third, we prepared a policy design that government can use as a guideline to integrate these approaches.

Engagement

At the beginning of the project, we knew we had to start by engaging with stakeholders to explain JREDD+. Our ultimate goal was to include the feedback and reflect relevant stakeholders’ needs—including the national government and public institutions, Indigenous groups, smallholder’s associations, NGOs, and educational institutions—in our results. We knew that communication between our research group and people who could be interested or potentially affected by the research project was crucial if we were to produce and share credible and legitimate knowledge. The knowledge acquired through these interactions can set the stage for an effective and equitable JREDD+ program in Colombia.

Source: Photos by Julián Gómez Gil.

In 2022, we hosted four engagement sessions in Tena (April 23 & 24, Cundinamarca), Florencia (May 5 & 6, Caquetá), Bogotá (October 14), and Mocoa (October 26 & 27, Putumayo). These sessions focused on the participation of representatives of the Amazon Indigenous peoples (OPIAC, OZIP, ACILAPP, etc.[2]), other local communities and land users (farmers, cattle ranchers, and smallholders associations), NGOs (Amazon Conservation Team, WWF, Natura Foundation, Fondo Patrimonio Natural, etc.), private organizations (Emergent, Amazon Global, Permin Global, ALLCOT, Asocarbono, etc.) and national and subnational government institutions (Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, Sinchi Institute, Corpoamazonía, etc.). During these community meetings, we worked hard to improve participation but also set realistic expectations, and engaged in open-ended discussions where training was provided to the attendees regarding the formulation of projects of conservation, carbon markets, REDD+ projects, JREDD+ programs, guidelines of the ART-TREES standard and the operation of the LEAF call for proposals, through technical presentations and educational activities, and promoting the constant participation of the actors to create scenarios for debate and resolution of doubts.

In the same way, these spaces were used to formulate questions to the different actors, which were resolved both through open debate dynamics and through collaborative work activities, taking advantage of a closer and more direct dialogue with each one of them and a greater availability of time to delve into topics of interest. This form of participation was very well received by the Indigenous Peoples, who invited the work team to implement similar activities more frequently and in the most remote territories so that capacity building can be held and the local context is better perceived.

Given the scale of a JREDD+ program, the interaction and negotiation between local actors, institutions, intermediaries, and current individual REDD+ projects are essential. According to the discussion with stakeholders, a common problem associated with the participation of key actors and interested parties in individual REDD+ projects is that these actors tend to be treated as beneficiaries rather than partners. As a result, local communities and interested parties perceive that the design of incentives, local capacity, delivery mechanisms, transparency provisions, and distribution are only partially fair. This led us to consider fairness, representation, and transparency as critical components of policy design.

Modeling

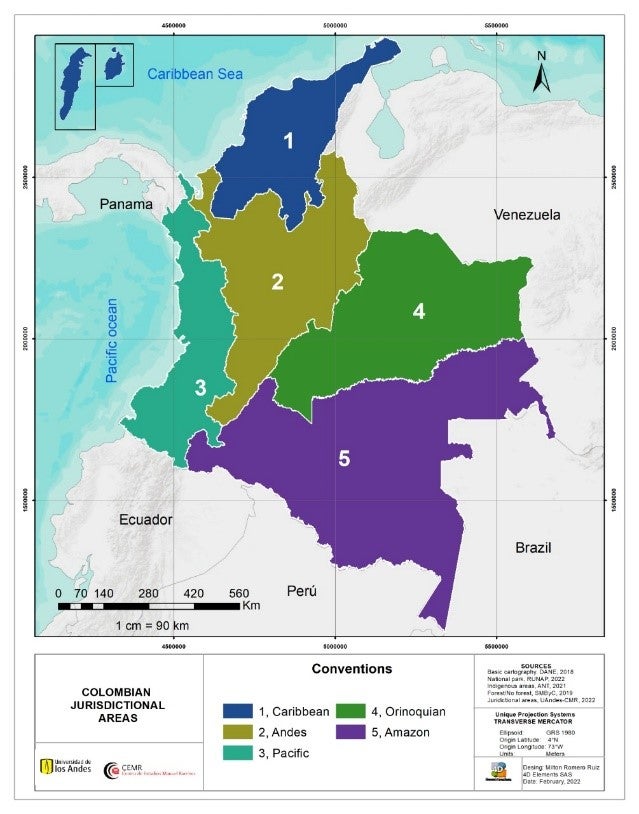

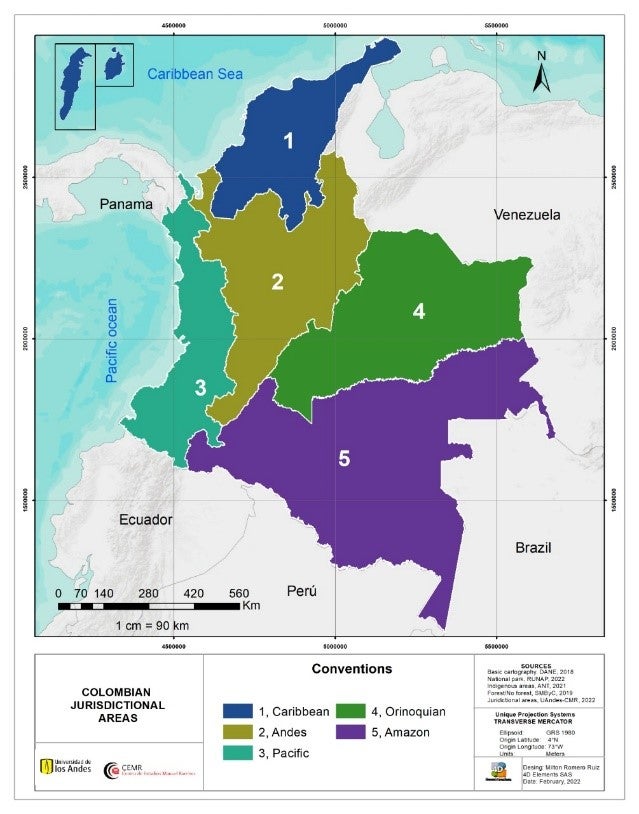

We modeled a mechanism to integrate the potential funds generated with a JREDD+ and a national emissions trading system (ETS) to accelerate the reduction of emissions from deforestation. Mainly, we considered a scenario under which Colombia applies the LEAF coalition model on a national scale of a JREDD+ at the national level. At the same time, to ensure representativeness, bargaining power, effective resource administration, and a fair distribution of benefits, we proposed an internal administrative division of Colombia into five jurisdictions: 1. Caribbean region; 2. Andean region; 3. Pacific region; 4, Orinoquía region; and 5. Amazon region.

Our modeling revealed that integrating a JREDD+ program with a National ETS could be a cost-efficient mechanism to reduce the externality costs and disincentivize the overall GHG emissions of Colombia following the country’s regulatory framework, the emissions trajectory, and the mitigation objectives. These mechanisms could be used to generate and allocate economic resources to ensure efficient emissions mitigation, the incorporation of safeguards (such as environmental education), and the minimization and/or compensation of adverse socio-environmental interventions. In addition, the modeling results imply the generation of co-benefits (economic, social, and environmental) that contribute to the development of ethnic communities, local communities, and other private land users.

Policy Design (Results)

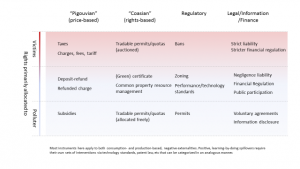

After receiving input from stakeholders and results from our model, we prepared a policy design that the government can use as a guideline to integrate JREDD+ inclusively and equitably. Here are our results:

- Inclusive negotiating for benefits-sharing: To build a JREDD+ in Colombia, stakeholders demand a significant role in negotiating the benefit-sharing system. In this regard, national and subnational agreements should be established to achieve at least the following three main objectives: 1) provide effective monetary and non-monetary incentives; 2) contribute towards building legitimacy through a fair and equitable distribution of resources, responsibilities, and bargaining power; 3) include local actors in the decision-making process and recognize them as partners rather than beneficiaries.

- Use vertical and horizontal benefit-sharing to equitably distribute benefits and negotiating power: A vertical benefit-sharing approach uses national voluntary and regulated market funds (ETS) to distribute benefits among national and subnational governments, non-governmental actors, intermediaries, NGOs, and facilitators. These transactions are carried out to ensure the operability of the program. On the other hand, horizontal benefit-sharing seeks to distribute the remaining benefits as incentive payments among and within communities, households, and local stakeholders. A fair design of benefit sharing must be vertical and horizontal to guarantee the bargaining power of the actors involved in deforestation and conservation activities.

- Centralize decision-making, but include regional representation: Our main policy proposal is to centralize the decision-making with a single National Board of Directors. This board would be responsible for making central decisions and directly managing the resource flow. On the other hand, a Jurisdictional Board of Directors composed of representatives from each of the six jurisdictions must be created to guarantee the representativity and bargaining power of the different actors. This board will function as a participatory body overseeing operational decisions that a respective Jurisdictional Operating Unit should execute. With this management structure, it is possible to use the three sources of funding (JREDD+ results-based payments, the ETS, and the carbon tax) and to effectively distribute the benefits among implementing partners (NGOs, private sector, etc.) and land users (Indigenous Peoples, local communities, farmers & ranchers, etc.)

- Leverage allowances from emissions trading system to support efforts to conserve forests: In our study, we assumed that much-needed finance for forest protection may come from two different sources: a nationally managed fund constructed using resources from the international voluntary market and from a locally regulated market (a national ETS), where regional and local public and private institutions intermediate implementation with local communities; and a project-based fund where national or international funding goes directly to projects, with resources from both the national general budget and payment by results or other international cooperation (JREDD+). To integrate both mechanisms and be consistent with Colombia’s climate law, we propose that 20% of the cap established by the ETS can be offset with forestry emissions reductions using a jurisdictional approach. In that way, the allowances allocated by the ETS to the forestry sector will generate an additional source of income to reduce deforestation.

You can read more about our study and policy design here. In general, our recommendations in this project were derived and enriched from the participatory processes we carried out. The participants’ comments helped us to refine, redefine, and validate these recommendations.

As Colombia works toward implementing its Emissions Trading System by 2030, we encourage them to consider these recommendations to inclusively and equitably incorporate JREDD+. We encourage them to consult with stakeholders such as Indigenous and locally affected communities to develop climate policy.

[1] The Colombian Emissions Trading System is scheduled to be implemented by 2030 according to the Law 1931 of 2018 and Law 2126 of 2021.

[2] OPIAC- National Organization of the Indigenous People of the Colombian Amazon, OZIP- Organization of Indigenous People of Putumayo Department, ACILAPP- Association of Traditional Authorities of the Indigenous Peoples of Leguizamo Municipality and Upper Predio Putumayo Territories