Q&A accompanying a re-broadcast of a PBS NewsHour segment featuring Climate Shock:

Everyone is talking about 2 degrees Celsius. Why? What happens if the planet warms by 2 degrees Celsius?

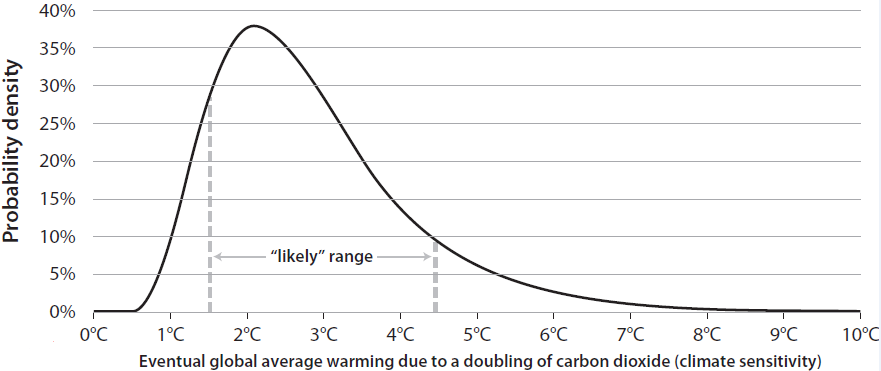

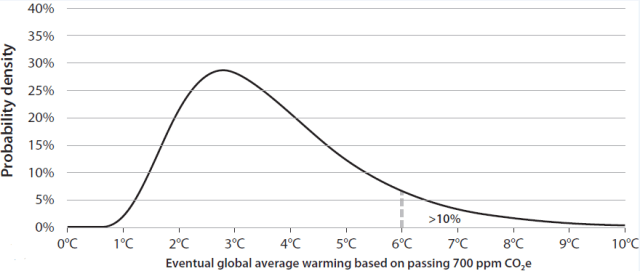

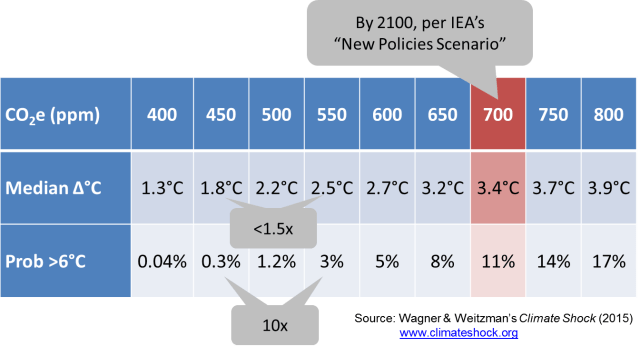

Martin L. Weitzman: Two degrees Celsius has turned into an iconic threshold of sorts, a political target, if you will. And for good reason. Many scientists have looked at so-called tipping points with huge potential changes to the climate system: methane being released from the frozen tundra at rapid rates, the Gulfstream shutting down and freezing over Northern Europe, the Amazon rainforest dying off. The short answer is we just don’t — can’t — know with 100 percent certainty when and how these tipping points will, in fact, occur. But there seems to be a lot of evidence that things can go horribly wrong once the planet crosses that 2 degree threshold.

In “Climate Shock,” you write that we need to insure ourselves against climate change. What do you mean by that?

Gernot Wagner: At the end of the day, climate is a risk management problem. It’s the small risk of a huge catastrophe that ultimately ought to drive the final analysis. Averages are bad enough. But those risks — the “tail risks” — are what puts the “shock” into “Climate Shock.”

Martin L. Weitzman: Coming back to your 2 degree question, it’s also important to note that the world has already warmed by around 0.85 degrees since before we started burning coal en masse. So that 2 degree threshold is getting closer and closer. Much too close for comfort.

What do you see happening in Paris right now? What steps are countries taking to combat climate change?

Gernot Wagner: There’s a lot happening — a lot of positive steps being taken. More than 150 countries, including most major emitters, have come to Paris with their plans of action. President Obama, for example, came with overall emissions reductions targets for the U.S. and more concretely, the Clean Power Plan, our nation’s first ever limit on greenhouse gases from the electricity sector. And earlier this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a nation-wide cap on emissions from energy and key industrial sectors commencing in 2017.

It’s equally clear, of course, that we won’t be solving climate change in Paris. The climate negotiations are all about building the right foundation for countries to act and put the right policies in place like the Chinese cap-and-trade system.

How will reigning in greenhouse gases as much President Obama suggests affect our economy? After all, we’re so reliant on fossil fuels.

Gernot Wagner: That’s what makes this problem such a tough one. There are costs. They are real. In some sense, if there weren’t any, we wouldn’t be talking about climate change to begin with. The problem would solve itself. So yes, the Clean Power Plan overall isn’t a free lunch. But the benefits of acting vastly outweigh the costs. That’s what’s important to keep in mind here. There are trade-offs, as there always are in life. But when the benefits of action vastly outweigh the costs, the answer is simple: act. And that’s precisely what Obama is doing here.

And what steps should the countries in Paris this week take to combat climate change?

Martin L. Weitzman: If it were entirely up to me, I would have a very simple solution: negotiate one uniform price on carbon dioxide applicable to everyone. That doesn’t mean some imaginary world government would be in charge — not at all. Every country — every government — can implement their own policy, keep the revenue and decrease taxes elsewhere. But the price is universal across the world.

Gernot Wagner: Pricing carbon, of course, is indeed the answer. It’s the obvious one or at least it should be. Now, the negotiations themselves, of course, are messy, and there currently is no negotiation around a uniform, globally applicable carbon price. Instead, what’s happening is many large countries — the U.S., the EU, and chief among them China — are putting forward internal policies that will put a price on carbon and other greenhouse gases. That’s also where Paris comes in: putting a framework on all these country actions.

Are you hopeful?

Gernot Wagner: I am. The climate problem is, in fact, a lot worse than many people realize. The climate shock is real. But there are solutions. They work. They are getting better and cheaper by the day. And we are largely moving in the right direction.

Martin L. Weitzman: Climate change is an extremely difficult problem to solve, certainly among the most difficult I have seen in my lifetime. But I’m guardedly optimistic, yes.

Gernot Wagner: In the end, it’ll take Washington, Wall Street and Silicon Valley to make this right by pricing carbon, deploying clean technologies at scale and investing in research and development that will lead to new, even cleaner technologies we can’t yet even imagine. A lot is happening on all these fronts. A lot more, of course, needs to be done.

Originally published on the PBS NewsHour Making Sen$e blog, on December 3rd, 2015.