What Happened?

Last month, FDA’s scientists published the toxicological reference value (TRV) for exposure to cadmium in the diet. This value is the amount of a chemical—in this case cadmium—a person can consume in their daily diet that would not be expected to cause adverse health effects and can be used for food safety decision-making. The TRV was based on a systematic review FDA scientists published last year. We will turn to the TRV itself in an upcoming blog but are focusing on the systematic review here.

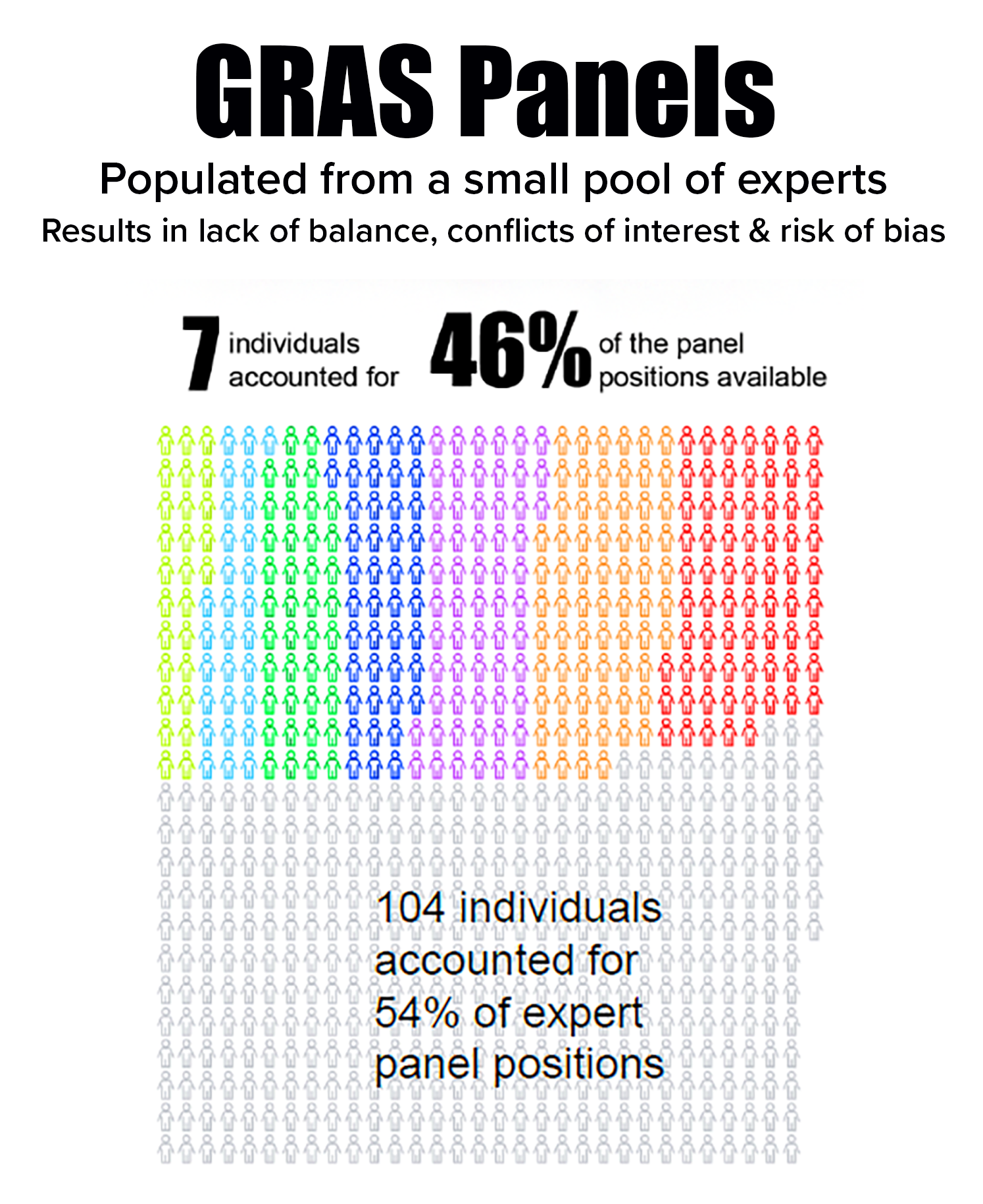

In a May 2023 publication, experts in systematic reviews from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) raised concerns about FDA’s “lack of compliance” from established procedures.

We discussed these concerns with FDA. They said:

- “The systematic review and the TRV” publication “have both undergone external peer review by a third-party and experts in the field.” The agency expects to publish the reviews on its website, and

- FDA “is working on developing a protocol for a systematic review of cardiovascular effects of cadmium exposure that will be published.”

Why It Matters

Systematic review is a method designed to collect and synthesize scientific evidence on specific questions to increase transparency and objectivity and provide conclusions that are more reliable and of higher confidence than traditional literature reviews. In particular, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have recommended the use of systematic reviews to establish values such as the TRV that may be used to inform regulatory decisions.

The National Toxicology Program (NTP) and others have developed specific methodologies to conduct systematic reviews. FDA’s authors said they followed NTP’s Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) handbook.

Unfortunately, FDA’s adherence to the methodology fell short on both transparency and objectivity grounds, undermining the credibility of its conclusions. Credibility is crucial because FDA’s authors stated that “this systematic review ultimately supports regulatory decisions and FDA initiatives, such as Closer to Zero, which identifies actions the agency will take to reduce exposures to contaminants like cadmium through foods.”

Read More »