Tom Neltner, Senior Director, Safer Chemicals

This is the sixth in our Unleaded Juice blog series exploring how the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sets limits for toxic elements like lead, arsenic, and cadmium in food and the implications for the agency’s Closer To Zero program.

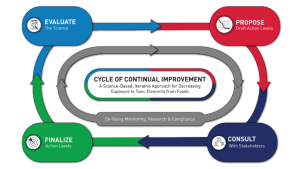

A core tenet of FDA’s Closer to Zero program is the “Cycle of Continuous Improvement” represented by the image below on the program’s webpage. The four-stage, outer ring represents FDA’s process for revising its action levels for food contaminants. The inner, grey ring describes the agency’s on-going monitoring, research, and compliance program.

This approach makes sense, and we fully support it. However, the success of this approach relies on FDA addressing several significant structural weaknesses.

- Future funding is not guaranteed: In March 2022, Congress appropriated $11 million in Fiscal Year 2022 (FY22) funding for FDA’s maternal and infant health work—in part to support the agency’s efforts to reduce arsenic, lead, and cadmium in children’s foods. Last year’s request and appropriations were a significant increase over previous years, but that funding level is not guaranteed for future years.

- Action levels are guidance—not legally binding requirements: FDA’s action levels for contaminants in food are established in guidance. The guidance introduction makes it clear that “The contents of this document do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way, unless specifically incorporated into a contract.” It assumes that the food industry—from the largest multinational corporation to the smallest entrepreneur—will comply.

- The agency has limited means to monitor compliance: FDA largely relies on physical inspections and market sampling, supplemented by voluntary reporting, to assure compliance with action levels. Inspections at high-risk facilities must occur every three years (but likely have been delayed due to the COVID pandemic). We understand that most facilities will see an inspector once every eight years. This is particularly problematic because FDA says it lacks the authority to require food companies to provide requested documents without the physical inspection, and the agency does not require ongoing testing and reporting by companies for action levels.

- Action levels must be consistently strong enough to drive research and impact markets: FDA correctly points to its success in setting an action level for inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal as a model to lower contamination. Unfortunately, the model assumes the action level for a contaminant is set low enough to result in research investments and increased product and ingredient testing and to provide FDA with sufficient information to act on problems. This is not the case for lead in juice.

We explore each of these weaknesses below.