The damage done, Part 2: A post-mortem on the Trump EPA’s assault on TSCA’s new chemicals program

Richard Denison, Ph.D., is a Lead Senior Scientist.

Part 2 of a 2-part series (see Part 1 here)

Last week’s announcement by EPA about improvements it is making to EPA’s reviews of new chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) indicated it will begin by reversing two of the most damaging policy changes the Trump EPA made to the program:

Under the Trump EPA policies being reversed, at least 425 new chemicals were granted unfettered market access despite potential risks or insufficient information.

- EPA will cease avoiding issuance of the binding orders TSCA requires to address potential risk or insufficient information:

“EPA will stop issuing determinations of ‘not likely to present an unreasonable risk’ based on the existence of proposed SNURs [Significant New Use Rules]. Rather than excluding reasonably foreseen conditions of use from EPA’s review of a new substance by means of a SNUR, Congress anticipated that EPA would review all conditions of use when making determinations on new chemicals and, where appropriate, issue orders to address potential risks. Going forward, when EPA’s review leads to a conclusion that one or more uses may present an unreasonable risk, or when EPA lacks the information needed to make a safety finding, the agency will issue an order to address those potential risks.”

- EPA will cease assuming workers are adequately protected from chemical exposures absent binding requirements on employers:

“EPA now intends to ensure necessary protections for workers identified in its review of new chemicals through regulatory means. Where EPA identifies a potential unreasonable risk to workers that could be addressed with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and hazard communication, EPA will no longer assume that workers are adequately protected under OSHA’s worker protection standards and updated Safety Data Sheets (SDS). Instead, EPA will identify the absence of worker safeguards as “reasonably foreseen” conditions of use, and mandate necessary protections through a TSCA section 5(e) order, as appropriate.”

If you want the details on what was wrong with these policies – legally, scientifically, and health-wise – see EDF’s comments submitted to the agency last year and a summary of them here.

It’s no accident that these two policies were prioritized for reversal. As I discuss below, each had massive adverse impact on the rigor and outcome of EPA’s reviews of new chemicals. The result was that the Trump EPA allowed many hundreds of new chemicals to enter commerce under no or insufficient conditions. It did this by: 1) illegally restricting its review to only the intended uses of a new chemical selected by its maker, hence failing to follow TSCA’s mandate to identify and assess reasonably foreseen uses of the chemicals; and 2) dismissing significant risks to workers that its own reviews identified, despite TSCA’s heightened mandate to protect workers.

Orders became a rarity, and testing virtually non-existent

I noted in Part 1 of this series that early implementation of the TSCA amendments largely adhered to the law’s new requirements. As anticipated and for very good reason, that led to EPA issuing many more orders imposing conditions on manufacturers of new chemicals than had been the case under the old law. A good number of those orders came with testing requirements – something that was also called for under amended TSCA in light of how few notices submitted for new chemicals included health and environmental data; TSCA specifically requires EPA to issue orders where the available information is “insufficient to permit a reasoned evaluation of the health and environmental effects” of the new chemicals (TSCA section 5(b)(3)(B)).

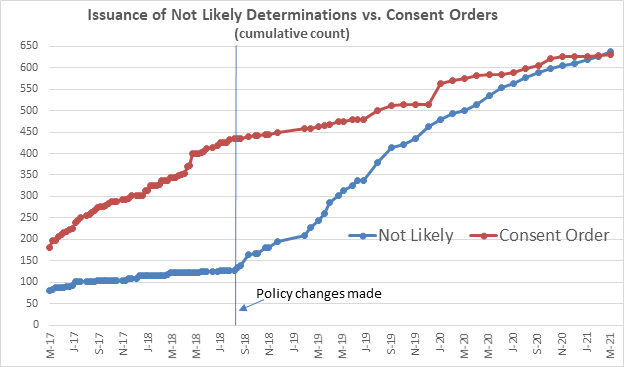

Industry bristled at these changes, to say the least. They took their complaints to then-Administrator Scott Pruitt and other industry-affiliated political appointees to demand change, and they got it. While it took some time (until mid-2018) for the changes to show up in individual decisions, the effect was dramatic. The chart below tracks EPA’s own statistics on the outcomes of its new chemicals reviews from May of 2017 (when EPA first began reporting the numbers) through March of this year. (EPA updates these statistics periodically, replacing the previous ones; I have captured them over this whole period, however, and used them to create the chart.)

The summer 2018 inflection point is impossible to miss: The issuance of orders flattened while “not likely” determinations soared – the inverse of what had transpired up to that point in time.

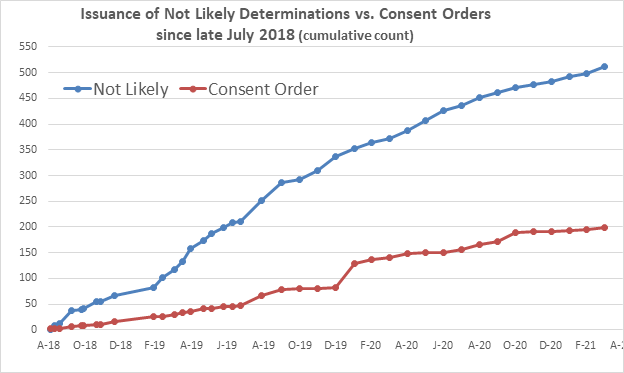

Let’s now zoom in to look in more detail at what happened after those policy changes took hold:

The bottom line: Nearly three-quarters of all new chemicals reviewed since mid-2018 after Pruitt’s policy changes got “not likely” determinations that cleared them to enter commerce without any conditions. That amounts to more than 425 new chemicals granted unfettered market access.

As for testing requirements, those would only come through an order; I can’t remember the last time I saw an order with any testing requirements. In fact, the Trump EPA stopped publicly posting orders altogether a year ago, so even the 50 or so such orders it did issue since then can’t be checked to see what they do and do not require of the companies. But if those we did have access to up to a year ago are any guide, the hidden ones won’t have testing requirements either.

Finally, the rigor of orders themselves appears to have been compromised by the Trump EPA: It colluded in secret with industry trade associations and law firms to weaken them, as we discovered through documents we obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request last month.

SNURs didn’t come close to keeping up with “not likely” determinations

Under the Trump EPA’s legally flawed approach, which the Biden EPA is now reversing, EPA sought to rely on its issuance of “Significant New Use Rules” in order to: limit its review of a new chemical to only those uses intended by the manufacturer; on that basis issue a “not likely” determination; and defer any consideration of reasonably foreseen uses of the chemical to some possible future review divorced from the first.

Initially, EPA leadership insisted that the “not likely” finding would be made only once a final SNUR had been promulgated. That then slipped to have issuance of the finding coincide with the proposal of the SNUR. That then slipped further to allow the finding to be issued based on EPA’s mere intent to develop a SNUR.

So how did that go? Since mid-2018, SNURs have been proposed for fewer than half (48%) of the new chemicals getting “not likely” determinations. And for only 19% have the SNURs actually been finalized.

As to when the SNURs were issued, for only 12 of 206 “not likely” new chemicals with proposed SNURs was the SNUR proposed before the chemical was approved. For those with proposed SNURs coming after approval, they didn’t get proposed until, on average, 90 days after the chemical was approved. And not a single one of the 19% of “not likely” chemicals with a final SNUR had that SNUR in place before the chemical was approved without condition; in fact, those final SNURs lagged approvals by an average of 10 months.

So much for the Trump EPA’s plan to make its “not likely” determinations dependent on SNURs.

EPA cleared hundreds of new chemicals that by its own analysis present risk to workers

One of the most egregious acts by the Trump EPA under TSCA was its utter disregard for the elevated risks workers face from chemical exposures. Embracing industry’s illegal demands that EPA stay out of workplaces – even though TSCA specifically identifies workers as warranting special protection as a vulnerable subpopulation – the Trump EPA systematically dismissed even very high worker risks its own analysis identified.

To do so, EPA made assumptions about worker protections that 1) were not supported by any actual evidence; 2) grossly distorted the regulations and authorities of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA); and 3) are wholly inconsistent with the longstanding Industrial Hygiene Hierarchy of Controls (HOC) embodied in both OSHA policy and that of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The HOC emphasizes removing chemical hazards from workplaces as the first and best worker risk management option. (EPA instead chose to focus on the HOC’s option of last resort: assuming workers would always don fully effective personal protective equipment (PPE) even absent any requirement for their employers to provide it.)

How extensively did EPA rely on this nefarious approach? Of the 425 “not likely” determinations the Trump EPA issued since Pruitt’s damaging policies took hold, nearly 80% identified some risk to workers – but then dismissed it by assuming workers would and could protect themselves by using PPE. Ironically, by so doing, EPA eviscerated its only opportunity to actually impose through an order workplace controls sufficient to mitigate the risk.

While we are pleased to see EPA’s decision to reverse this policy, it is vital that EPA adhere to the HOC in addressing workplace risks and not merely make PPE use mandatory.

I blogged last summer about the magnitude of the workplace risks EPA found and dismissed. In this updated table, I have catalogued the exceedances of the Trump EPA’s own risk benchmarks in its 80 most recent “not likely” decisions, made since June 2020, including those made since my previous post. Here are the overall findings:

- For 41 of the 80 cases, the risks to workers EPA identified exceeded its own benchmarks for dermal or inhalation exposures, or both.

- In 36 cases, EPA’s dermal risk benchmark was exceeded.

- In 16 cases, EPA’s inhalation risk benchmark was exceeded.

- In 11 cases, EPA’s dermal and inhalation risk benchmarks were both exceeded.

- The magnitude of the exceedances was as follows:

- The median “fold factor” (i.e., magnitude of exceedance) across the 36 dermal exceedances was 15-fold, ranging from 1.1 to 31,000.

- The median “fold factor” across the 16 inhalation exceedances was 4-fold, ranging from 1.0 to 20.

- For 53 of the 80 cases, EPA identified additional hazards the chemicals pose but it did not quantify the risk “due to a lack of dose-response for these hazards.”

This extent and magnitude of risks to workers that were routinely dismissed through false assumptions should serve as a staggering indictment of the Trump EPA’s willingness to elevate private industry interests over the agency’s mission.

In sum, a lot of damage was done over the last four years, and it is incumbent on the Biden EPA to act aggressively to ensure the irresponsible policies of the last administration that caused the damage are undone.