It’s time to eliminate lead from tin coating and solder on metal food cans

Tom Neltner, J.D. is the Chemicals Policy Director.

In October 2019, we reported finding canned foods had a surprising number of samples with lead based on the Food and Drug Administration’s testing results. Almost half of the 242 samples had detectable lead, including a staggering 98% of 70 canned fruit samples.

We suspect that the high lead detection rates are a result of lead in the tin – either added to make an alloy or as a contaminant – used to coat the steel or join steel pieces together in the cans. This lead can then leach from the coating or solder into the food. Light-colored fruits and fruit juices would be more likely to have lead contamination based on a report indicating they are commonly packaged in tin-coated steel cans without a synthetic coating on the inside isolating the food from the tin. The lead detections in the other canned products in FDA’s study could have resulted from flawed synthetic coatings.

In December 2020, EDF and ten health, consumer, and environmental groups[1] petitioned FDA to ban the use of lead in food contact materials such as tin. We also included that FDA should presume that lead was intentionally used when levels in food contact materials are at or above 100 parts per million (ppm) and provided an option for the agency to specifically authorize the use only if:

- The part of the food contact article that contains added lead does not contact food under intended conditions of use; or

- No lead migrates into food from the food contact article under intended conditions of use.

Our petition demonstrates that, because lead is a carcinogen that is unsafe at any level in the blood, its use in tin coatings and solder for food cans should be expressly prohibited. The agency posted the petition for public comment and must make a decision how to proceed by June 2021. There is no deadline for comments, but it is best to submit them by April 1 so they can influence the agency’s decision.

FDA’s testing data on canned food

FDA’s Total Diet Study (TDS) is an important source of data for both the agency and the public to estimate exposure, track trends, and set priorities for chemicals such as heavy metals in food. In 2017, EDF analyzed results from samples the agency collected from 2003-13, finding widespread contamination with 20% of baby food samples and 14% for other foods having detectable levels of lead.

When we evaluated FDA’s TDS data from 2014-17 that had been tested using a more sensitive analytical method than had used for 2003-13 data, we found lead detected in 29% of baby food samples and 26% for other foods. Many of the foods with frequent lead detections such as sweet potatoes, grapes, carrots, peaches, squash, and pears could be attributed to contamination in the field where they are grown.

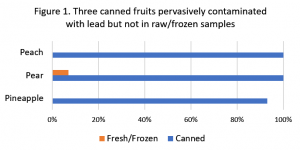

We also noticed the relatively high percentages of canned foods with detectable lead.[2] When we looked at three canned foods – peach, pear, and pineapple – that had a raw or frozen counterpart, we found that only 1 of 31 raw or frozen samples of those fruits had detectable lead compared to 41 of 42 for their canned versions. See Figure 1.

We saw similar, though not as dramatic, differences when we looked at the data from 2003-13 that used the old, less sensitive method.[3]

Clearly lead is entering food from the canning process and not from the fruit itself.

Sources of lead from the canning process

The most likely source is the lead-tin solder alloy used to join steel together. FDA first approved the use in 1939. The agency banned lead in can solder in 1995 after companies reported ending domestic use of the material four years earlier. However, the agency failed to define the term “lead solder” at § 189.240 and did not set a maximum amount of lead that solder could contain.

FDA’s 2017 version of the Food Code, a guidance for food establishments to keep food safe, specifically allows solder to have up to 0.2% – or 2000 ppm – lead. It would only take a minuscule fraction of solder at this limit leaching into the food to exceed FDA’s 3 micrograms daily maximum intake level for lead[4] for a child.

Lead-tin solder was also used to join copper pipe in drinking water systems. In 1986, Congress limited lead in solder to 0.2% – or 2000 ppm – and called it “lead-free solder” – a misleading name for something that can still have lead added to it. We assume that FDA’s Food Code was relying on the limit in solder for drinking water.

Beyond joining steel together, tin was – and still is – used to coat metal cans to prevent corrosion and spoilage. We would expect that the tin used in the coating may also have some lead – whether added or as a contaminant.

Food contact materials subject to more protective safety standard than drinking water

When FDA banned lead in can solder, it does not appear to have considered setting a numerical limit on the amount of lead the replacement solder could contain. While we do not know for certain, we think the industry in the 1990s might inadvertently have considered the “lead-free solder” allowed for drinking water uses not realizing the situations are quite different. In food cans, the food is in contact with the container for a long time allowing for more lead to be leached from the coating, while for drinking water the contact is much shorter. And beginning in 1994, drinking water was often treated to limit lead leaching.

For drinking water, Congress explicitly allowed 0.2% lead in solder for drinking water and 0.25% in other materials. In contrast, for food contact materials, in the Food Additives Amendment of 1958, Congress did not set a limit on lead; rather it required that the FDA approve the use only after applying a more protective safety standard. These standards require that additives not be used unless there is a reasonable certainty of no harm from their intended use after taking into account related substances in the diet. It also prohibits use of carcinogens. Lead is unsafe under both these restrictions because it is a carcinogen and no safe threshold has been found for lead in the blood to prevent neurologic development harm in children and heart disease in adults.

Progress on protecting children and adults from the risks posed by lead takes a concerted effort to drive down all sources of exposures. The use of lead in tin coatings and solder is unnecessary; safer alternatives are available. We anticipate that the FDA will take prompt action to adopt our petition.

[1] Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, Center for Food Safety, Clean Label Project, Consumer Reports, Defend Our Health, Environmental Working Group, Healthy Babies Bright Futures, and Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environmental.

[2] The canned foods that had no more than 1 in 14 detects from 2014-17 with lead include beets, corn, green beans, pork and beans, tuna and some varieties of soup.

[3] Percent detected: Peach – canned 78% v. raw 4%; Pear – canned 59% v. 4%; Pineapple – canned 55% v. juice 0%

[4] FDA refers to it as the Interim Reference Level, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention terminology for lead in blood. For basis of FDA’s calculation, see Flannery BM et al., U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s interim reference levels for dietary lead exposure in children and women of childbearing age. 2020. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 110:104516, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.104516.