Grain elevator. Credit: Flickr user Wilson Hui

A new study out this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that trying to make supply chains more sustainable is not for the faint of heart, especially when it comes to food – and corn in particular.

Companies are keenly aware that consumers care about where their ingredients come from and how they were grown, and that improving efficiencies along the supply chain can be good for business. But the raw ingredients at the end of those chains are typically produced by a vast network of farmers who bring their corn to regional grain elevators and then sell their crops to grain traders. This is just the start of a lengthy and complicated process that can be challenging for food companies to disentangle and understand, let alone influence to become more sustainable.

That’s why the new study, which focuses on a corn supply chain model developed by the University of Minnesota’s Northstar Initiative for Sustainable Enterprise (NiSE), can be an important tool for empowering food companies with information that can help them tackle the tough job of supply chain sustainability.

Understanding corn’s footprint

Corn is grown across approximately 90 million acres in the United States – equivalent to the size of California. While corn production has grown much more efficient over time and farmers have made amazing strides in adopting a range of conservation measures, on average just 40 percent of the fertilizer applied to U.S. crops is absorbed by plants that season. This means the rest is at risk of running off into waterways or escaping into the air – which can lead to water and air pollution, as well as lost income for farmers.

Corn is grown across approximately 90 million acres in the United States – equivalent to the size of California. While corn production has grown much more efficient over time and farmers have made amazing strides in adopting a range of conservation measures, on average just 40 percent of the fertilizer applied to U.S. crops is absorbed by plants that season. This means the rest is at risk of running off into waterways or escaping into the air – which can lead to water and air pollution, as well as lost income for farmers.

Understanding corn’s environmental footprint is fundamental to generating solutions that help farmers improve efficiencies, reduce fertilizer losses, and ultimately improve productivity. This knowledge also helps companies to meet and measure the success of their sustainability commitments and goals, and to mitigate risks such as supply chain disruptions from extreme weather events.

Corn supply chain model

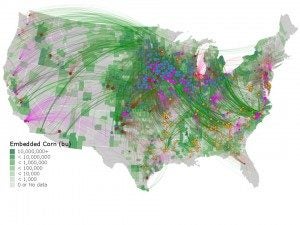

Predicted corn and animal movements for the 2012 ethanol, beef, hog and broiler industries.

Environmental Defense Fund wanted to find a way to make it easier for companies to evaluate their corn supply chain, so we reached out to NiSE, an organization with deep expertise in the complex agricultural supply chain, to develop a feed grain transport model that estimates emissions from grain farming.

EDF and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture both supported NiSE’s work to generate this model and give companies a starting point for understanding their grain supply chains.

I previously interviewed Jennifer Schmitt, Ph.D, director of the NiSE, who noted that the model is ultimately meant to show how corn and soy travel through the farm-to-feed-to-food pipeline in the U.S.

During this interview, Jennifer noted:

“The model, which uses publically available data, tracks corn and soy supplies from county-level crop production to county-level crop consumption, including feedlots and grower farms. It accounts for virtually all corn demand in the U.S. The model then estimates the additional movement of animals and their embedded feed grains to primary processing facilities. These facilities are connected to companies, making it possible to estimate the spatial sourcing of crops by meat producers.”

Because the model used publicly available data, it does not utilize any confidential company or farmer data, and does not go to the individual farm level.

How companies are using the model

As a Bloomberg article on the study noted, Smithfield Foods has already used the model in its work with EDF and NiSE to set a goal of reducing the company’s greenhouse gas emissions 25 percent by 2025. Smithfield provided NiSE with information that helped them refine the greenhouse gas assessment that underpins the company’s sustainability targets. Smithfield can now use the model to make its sustainability investments in areas where they will generate the greatest and most cost-effective improvements.

As Jennifer told me last year:

“The more we as researchers, practitioners and companies themselves know about corporate agricultural supply chains, the better equipped we are to identify opportunities for increasing sustainability to scale.”

Companies that proactively make decisions based on information tailored to them instead of industry averages have a much better chance at identifying win-wins that benefit the environment, farmers, and companies themselves.

While no model is perfect, including this one, it is important to use it for its intended purpose – in this case, education and understanding. This is not a tool to use for tracking or accountability for supply chain impacts. The goal is to empower stakeholders with information that can drive sustainability improvements – something that we should all be able to get behind.

Related:

How Smithfield’s landmark climate goal benefits farmers and the planet >>

3 ways NGOs can help sustainable supply chains grow >>

Unlocking the black box of agricultural supply chains >>