What does the end of the Paris deal mean for agricultural innovation?

No matter your views on climate change, the United States’ exit from the Paris agreement could compromise the ability of farmers and agribusinesses to become more resilient in the face of extreme weather events.

In the absence of federal leadership, individual farmers, state and national ag associations, food companies, retailers, and environmental organizations will need to fill the void.

I’m confident we can do this, because all the farmers I’ve ever known are incredible innovators and are willing to implement practices that can mitigate the effects of an unpredictable climate – practices that also protect their businesses.

[Tweet “Agricultural innovation is more important than ever, says @FriedmanSuzy.https://edf.org/8qE”]

More crop per drop

In his book, From Poverty to Prosperity, Nick Shultz notes, “Maybe there is no free lunch, as the saying goes; but we do not have to work nearly as hard to put food on the table as we used to. Just two hundred years ago, over half of all Americans worked in agriculture. Today, the figure is less than two percent.”

From improved seeds to precision agriculture technologies, today’s farmers can produce more crops with far less inputs.

According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, a farmer in 1970 could plant 40 acres of row crops in a day each spring, and in the fall could harvest 4,000 bushels per day. Today, farmers can plant 945 acres a day and harvest 50,000 bushels a day. Using 1940 methods and tools, the US would have needed another 150 million hectares to grow what they grow today, which is three times the size of Spain.

Continuous improvement

The point in looking back in awe at these advancements is to recognize how desperately we need that same pace of innovation to continue as we face an ever-changing climate.

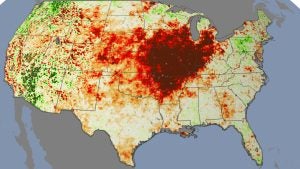

Agriculture has faced increasing disruption from extreme weather and climate shifts over the past 40 years, and this trend is expected to increase over the next 25 years. However, through changing crop rotations, adjusting planting times, technological advancements, as well as fertilizer, pest and water management – farmers can make their crops more resilient.

Take, for example, the story of my friend Brent Bible. I visited Brent at his farm in Indiana not long after the severe drought in the Midwest in 2012. Brent estimated that practices such as conservation tillage, cover crops and precision use of nutrients meant he got about 70 percent of his normal yield that year while many of his neighbors had no yield at all. These practices didn’t just help the environment, they were key for his business, too.

Keeping the momentum

I’m disappointed by the new Administration’s decision – not just because I am an environmentalist, but also because it slows momentum for implementing practices that help both farmers and the planet. For example, using fertilizer more efficiently saves money and reduces emissions, capturing methane emissions from manure can generate energy, and planting riparian or forested buffers alongside farmland can reduce erosion and sequester carbon.

I realize that the Paris agreement may not be top of mind for most farmers, and it’s unlikely that the industry will join states like Washington, California or New York in independently committing to the Paris agreement.

Instead, my hope is that farmers and the agricultural sector will continue to innovate – even if behind the scenes – to continue improving the way we produce food, taking these solutions to scale and exporting them to the world. Climate-smart agriculture practices can protect food security in uncertain times.

This post originally appeared on AgWeb and is used with permission.

Related:

How animal agriculture can help meet the Paris Climate Agreement goals >>

Agriculture doesn’t have a seat at the Paris climate talks, but we can’t wait for innovation >>

How agriculture can help drive a low-carbon economy >>