Why I promote the value of America’s farms and ranches

When I tend my garden at home near San Francisco, the words of writer and environmentalist Wendell Berry echo in my head: “We learn from our gardens to deal with the most urgent question of the time: How much is enough?”

I do everything I can to conserve. I grow food that has a minimal impact on the environment, I use a drip irrigation system, I compost to minimize waste and collect shower water to reuse on my plants.

In my professional life, I work with large-scale farmers to reduce their environmental footprint while protecting their livelihoods. My job sheds light on the importance of ensuring food security by looking closely at how and where we grow food.

I’m driven by what I learned growing up in a rural farming town, and from my years in the Peace Corps in Mali. These experiences are the reason I work to preserve the complexity of the agro-ecosystems around me.

Seeing cows for the first time

I grew up in upstate New York, in a small rural town on the banks of the St. Lawrence River near the Canadian border. Dairy farms dominate the landscape. When I was a kid, low-income children from New York City visited the area through the Fresh Air Fund summer program. Some of them had never seen cows and didn’t know where hamburger meat came from. I realized that as foreign as cities and urban communities were to me, that’s how foreign agricultural and rural communities were to them.

I grew up in upstate New York, in a small rural town on the banks of the St. Lawrence River near the Canadian border. Dairy farms dominate the landscape. When I was a kid, low-income children from New York City visited the area through the Fresh Air Fund summer program. Some of them had never seen cows and didn’t know where hamburger meat came from. I realized that as foreign as cities and urban communities were to me, that’s how foreign agricultural and rural communities were to them.

My memory of those kids remains with me today. I want to promote rural and urban collaboration and help to increase knowledge about the value of farms and ranches in America. How great would it be to have a Fresh Air-style program for adults to learn about how interconnected we all are?

Shea butter in Mali

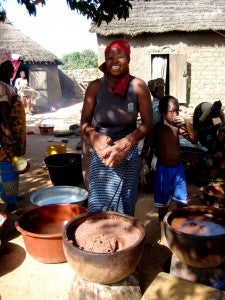

After studying international development in college, I joined the Peace Corps and found myself in another very small community halfway around the world in Mali. There, village women contribute to the local economy by producing shea butter, the ivory-colored fat extracted from the nut of the African shea tree. We are familiar with shea butter as a primary ingredient in lotions, but the local community uses it for cooking. My team worked with the women to improve production practices and make their shea butter more marketable.

Sometimes markets and buyers are blind to or misunderstand the incredible amount of effort that goes into the products they are buying. And as I saw in Mali, the prices that growers receive seem minimal compared to the time they invest.

This experience opened my eyes to how the sourcing of agricultural raw materials by global companies impacts producers on the ground, whether they’re farmers in California growing fruits and vegetables, growers in the Midwest harvesting corn, or a women’s collective in Mali producing shea butter.

Cap-and-trade can benefit farmers

Environmental Defense Fund has a unique approach to partnerships; we work with growers and corporations, focusing on science and economic policy. We listen to our partners’ concerns and propose solutions that accommodate different voices, without sacrificing our values.

This philosophy is apparent in my work with the agricultural greenhouse gas markets team. When we think of cap-and-trade, we normally think of factories polluting the air. But our natural ecosystems offer a lot of potential to offset the pollution caused by manufacturing and other industries. Through the use of climate-smart agriculture techniques and voluntary participation in California’s carbon market, growers earn credits they can trade for cash.

By optimizing fertilizer use, varying irrigation to better manage water, sequestering carbon in the ground and implementing the use of anaerobic manure digesters, farmers can reap economic benefits while they simultaneously increase the efficiency of their operations, make their land more resilient to climate change, mitigate emissions, and increase biodiversity on their lands.

Although producers aren’t always interested in participating in cap-and-trade, they’re often interested in adopting these practices because they save time, energy, water and other input costs. I love helping growers implement these techniques, regardless of their motivation, because they have a huge role to play in our climate’s uncertain future, a future that will impact all of us – from rural villages in upstate New York to rural villages in Mali.

Related Content

Why investments in agricultural carbon markets make good business sense >>

From my grandfather’s farm to NutrientStar: Why I believe in growers >>