By: Koko Iyoho, 2011 Climate Corps Public Sector Fellow at Trinity Episcopal Church in Asheville, North Carolina; MGIM graduate from North Carolina State University

By: Koko Iyoho, 2011 Climate Corps Public Sector Fellow at Trinity Episcopal Church in Asheville, North Carolina; MGIM graduate from North Carolina State University

My EDF Climate Corps Public Sector fellowship took me to Trinity Episcopal Church in Asheville, North Carolina. Listed in the National Register of Historical Places, Trinity is a 100-year-old structure that has 30,000 square feet. Trinity has three floors with two stained-glass enclosed sanctuaries, which illustrate the stories of the early church. Achieving energy savings without compromising the integrity of historical buildings poses quite a challenge. However, before my arrival, the church already took commendable energy efficiency initiatives: replacing 70% of T12 fluorescents with T8s, installing Energy Star office equipment, and upgrading its HVAC system. I found a lot of energy savings, but my most exciting finding took me to an unexpected place – “The Catacombs.”

My search for energy efficiency had begun with the basic areas of lighting and temperature settings. I found savings by installing lower wattage bulbs, replacing incandescent lights with fluorescents, switching to LED exit signs, and using temperature controls and setbacks. These retrofits showed significant energy and cost savings, but my financial analysis showed room for improvement. One clue was the basement floor, which has an uninterrupted cold air supply. The mystery was that Trinity’s basement had exceptionally high humidity levels despite the use of several dehumidifiers. To solve this puzzle, I put on my detective goggles and joined a weatherization expert to investigate the source of the high humidity. Our quest led us to “The Catacombs.”

The basement is referred to as The Catacombs because of its likeness to ancient underground cemeteries, but thankfully, without burial chambers. It is an underground area consisting of a network of tunnels, pipes, and ducts, but also of several mounds of bare earth. Basements are naturally prone to high levels of humidity because of moisture seeping from the earth outside the walls and floors. In this case, mounds of earth are piled up inside a significant portion of the basement, contributing to higher than normal humidity levels. We had solved the mystery. Also, according to the weatherization specialist, if the bare earth is encapsulated with a vapor barrier, along with other weatherization opportunities we identified, there is potential to save the church about 15% in heating and cooling costs with a 9-year payback. What great energy savings!

The basement is referred to as The Catacombs because of its likeness to ancient underground cemeteries, but thankfully, without burial chambers. It is an underground area consisting of a network of tunnels, pipes, and ducts, but also of several mounds of bare earth. Basements are naturally prone to high levels of humidity because of moisture seeping from the earth outside the walls and floors. In this case, mounds of earth are piled up inside a significant portion of the basement, contributing to higher than normal humidity levels. We had solved the mystery. Also, according to the weatherization specialist, if the bare earth is encapsulated with a vapor barrier, along with other weatherization opportunities we identified, there is potential to save the church about 15% in heating and cooling costs with a 9-year payback. What great energy savings!

With this finding, The Catacombs would no longer contribute to rising energy consumption at Trinity… not unless actual ghosts moved in.

EDF Climate Corps Public Sector (CCPS) trains graduate students to identify energy efficiency savings in colleges, universities, local governments and houses of worship. The program focuses on partnerships with minority serving institutions and diverse communities. Apply as a CCPS fellow, read our blog posts and follow us on Twitter to get regular updates about this program.

I have a background in renewable energy generation, which helped me analyze options for solar panels to curb energy consumption. I identified a section of roof at Groce that had perfect southern exposure and conducted a site assessment that yielded impressive results.

I have a background in renewable energy generation, which helped me analyze options for solar panels to curb energy consumption. I identified a section of roof at Groce that had perfect southern exposure and conducted a site assessment that yielded impressive results.

Jen and I work in Estey Hall, a beautiful, red brick administration building. It was constructed in 1864 as a dormitory for women. Because of its age, the building is difficult to uniformly heat and cool. Walking through the hallways and into rooms, we noticed defined layers of temperature. We decided to track thermostat settings to get to the bottom of these temperature discrepancies. What we found surprised us!

Jen and I work in Estey Hall, a beautiful, red brick administration building. It was constructed in 1864 as a dormitory for women. Because of its age, the building is difficult to uniformly heat and cool. Walking through the hallways and into rooms, we noticed defined layers of temperature. We decided to track thermostat settings to get to the bottom of these temperature discrepancies. What we found surprised us!

By: Jian Huo, 2011 Climate Corps Public Sector Fellow in

By: Jian Huo, 2011 Climate Corps Public Sector Fellow in

By: Jim Hildenbrand, 2011 Climate Corps Public Sector Fellow at

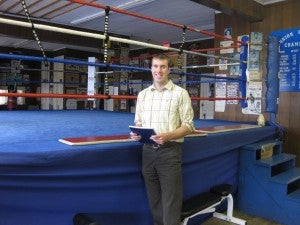

By: Jim Hildenbrand, 2011 Climate Corps Public Sector Fellow at  Now in the second half of my fellowship, the pace has not slackened and I am evaluating a variety of opportunities for energy savings. About 20 of Middletown’s buildings consume 9,000 megawatt-hours per year. Each building is unique and no two buildings serve the same purpose. While this adds to the challenge, it has been a lot of fun. I explored a turn of the century schoolhouse that was retrofitted into a boxing ring. I also traversed the floors of the headmaster’s house of a former all-boys school that is now used as the seat for the historical society, a gymnasium, and a drug rehabilitation program.

Now in the second half of my fellowship, the pace has not slackened and I am evaluating a variety of opportunities for energy savings. About 20 of Middletown’s buildings consume 9,000 megawatt-hours per year. Each building is unique and no two buildings serve the same purpose. While this adds to the challenge, it has been a lot of fun. I explored a turn of the century schoolhouse that was retrofitted into a boxing ring. I also traversed the floors of the headmaster’s house of a former all-boys school that is now used as the seat for the historical society, a gymnasium, and a drug rehabilitation program.