Three ways EPA’s upcoming methane regulations will help slow climate change and protect public health

In a move that will protect communities across the country, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will soon finalize new rules to reduce methane and other toxic, smog-forming pollution from the nation’s oil and gas industry.

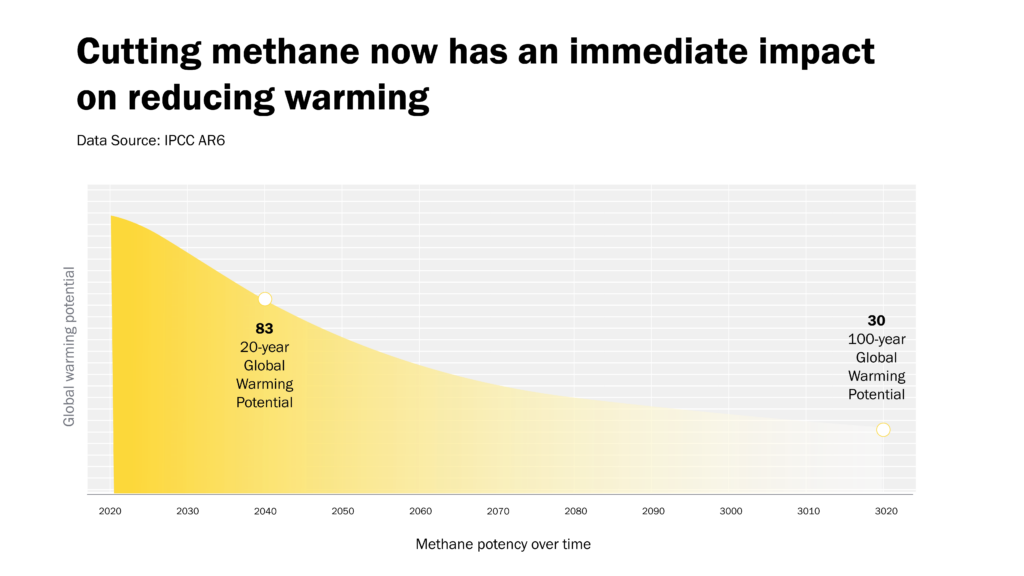

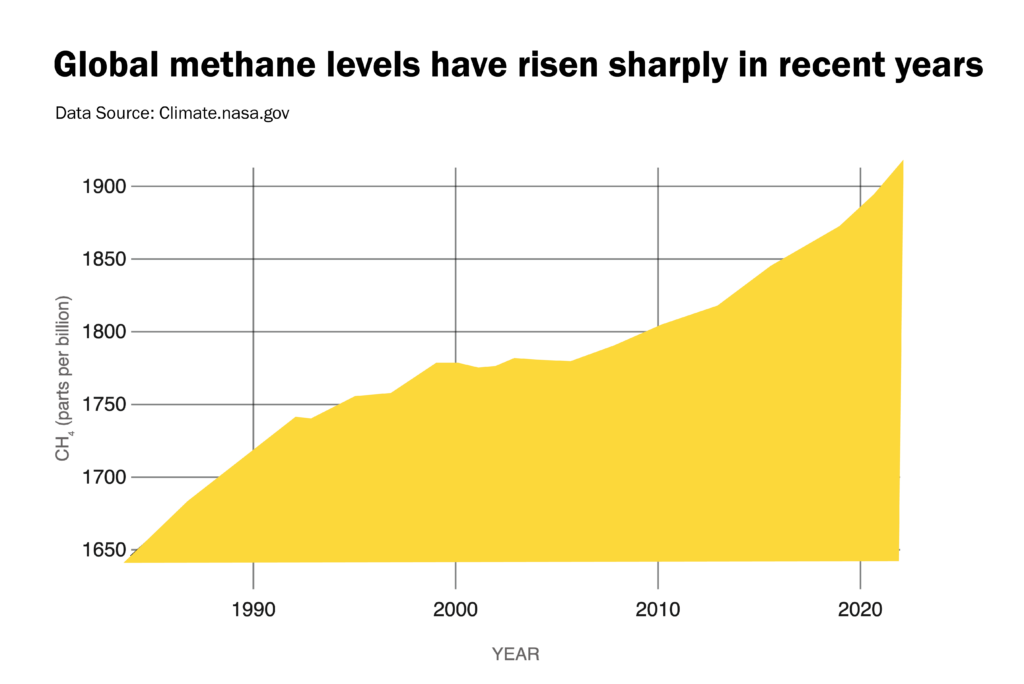

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that’s fueling much of the climate crisis due to the excessive warming it creates during its lifetime in the atmosphere. Methane makes up about 12% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., but it’s responsible for over 25% of current warming.

According to NASA, there’s more methane in the atmosphere today than at any other point in history. Climate research indicates that reducing methane can significantly slow the rate of global warming — buying us more time to adapt to the realities of a changing climate. As a result, reducing methane has become a major priority for countries across the globe.

Three ways EPA’s upcoming methane regulations will help slow climate change and protect public health Share on X

In the U.S. oil and gas operations are the largest industrial source of methane emissions. And according to the International Energy Agency reducing emissions from the oil and gas industry is the easiest, and most cost-effective way to achieve fast methane reductions. Methane essentially is natural gas, so reducing industry’s emissions ultimately helps eliminate billions of dollars worth of lost gas and conserve energy resources.

As one of the world’s largest methane emitters, the United States has a responsibility to reduce as much methane as possible to help prevent the most dire consequences of climate change. The agency estimates these new efforts could help reduce emissions from covered sources as much as 87% from what they were in 2005.

There are three critical updates from EPA’s most recent proposal that will help slash methane levels if carried over to final rules.

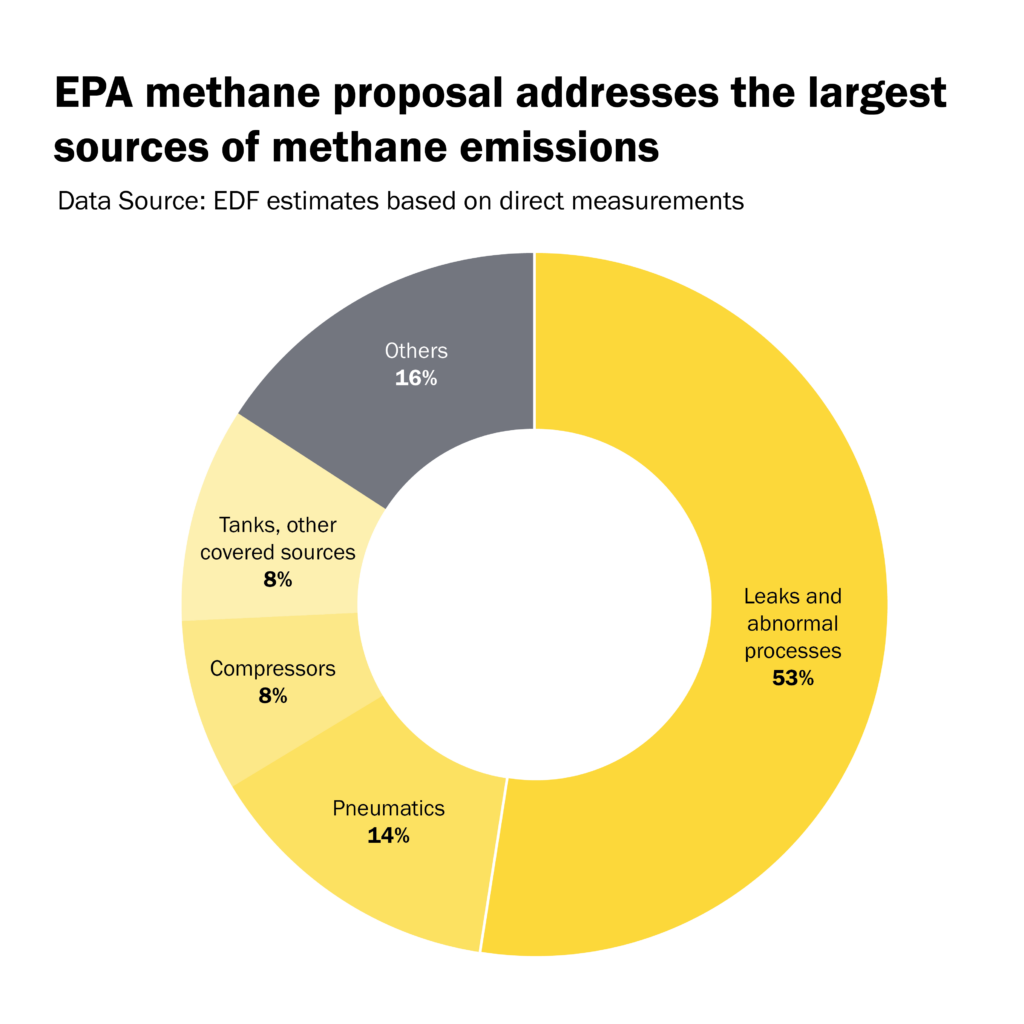

Eliminating pollution from pneumatics

Pneumatic controllers are equipment that help move gas through pipelines and other infrastructure and have shown to be significant methane emitters. They are often powered by the very gas they are moving, and are designed to leak gas as they operate, leading to systematic methane emissions. EPA’s plan to shift from gas-powered pneumatic controllers to clean, electric or air-driven versions builds upon actions taken by leading companies to eliminate polluting pneumatics and will significantly lower the industry’s methane footprint. EPA estimates that the transition to zero-emitting controllers will eliminate 19 million tons of methane by 2035, creating the same climate benefit as eliminating annual emissions of 300 million cars.

Comprehensive leak detection and repair

The agency most recent proposal also includes comprehensive leak inspections across all sites, including regular monitoring at smaller wells with leak-prone equipment. While these wells account for just 6% of production, recent studies have shown that cumulatively the emissions from these smaller wells account for half of all production emissions. Leaks and other abnormal events are responsible for the largest share of emissions, so requiring more frequent leak inspections at all facilities will help slash overall methane pollution. EPA has also proposed a flexible program that would enable companies to leverage proven advanced monitoring technologies, unlocking even deeper potential reductions. It also includes standards to reduce pollution from other high-emitting equipment like compressors and tanks. Additionally, the proposal requires companies to document that wells have been properly plugged to ensure they won’t leak methane after they’ve been shut in. By preventing wells from being improperly abandoned, EPA’s efforts will help protect surrounding communities against experiencing negative health impacts due to the pollution emitted from old, abandoned wells.

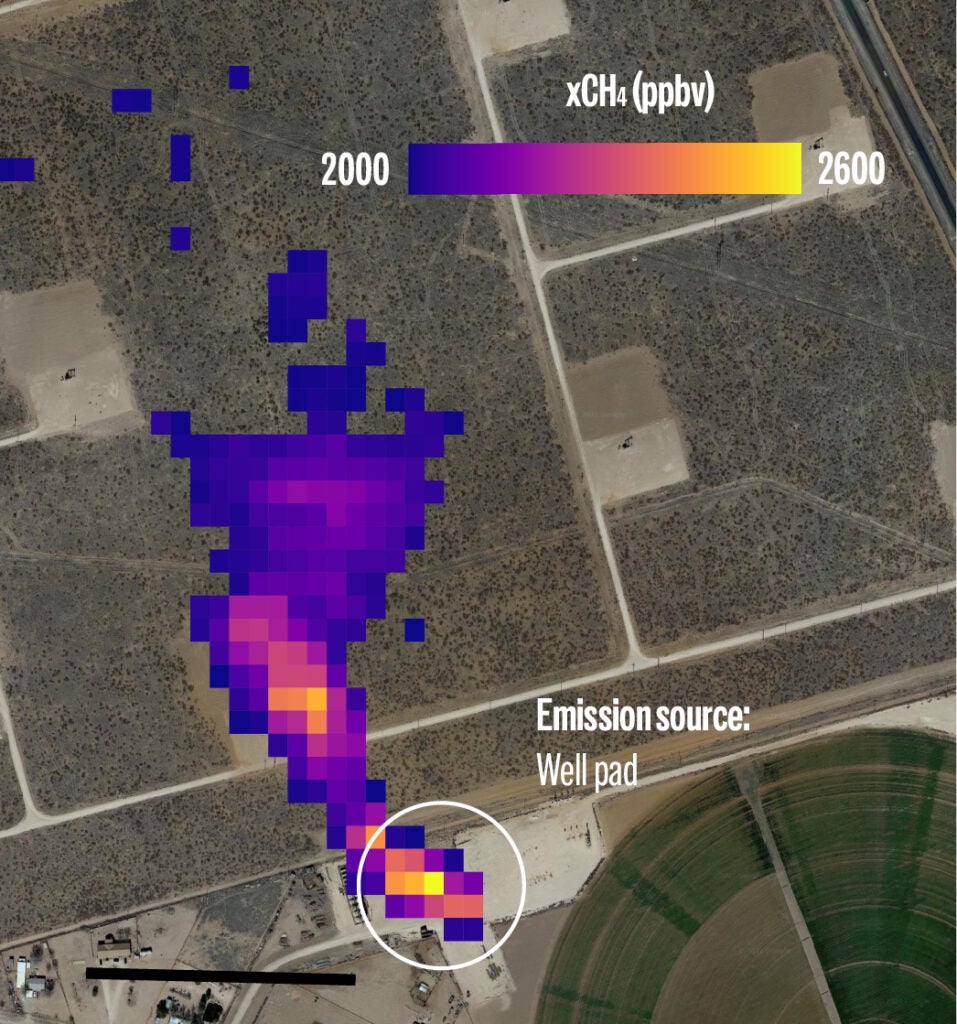

Reducing super emitters

Additionally, the proposal would create a super-emitter response program that will use data from third parties using verified technologies to help identify large emissions events that require immediate mitigation.

More to come on flaring?

For many years, it has been common practice for oil producers to burn off unwanted gas at oil wells in a process known as flaring. In addition to being wasteful, routine flaring also creates negative health and environmental impacts. A recent study in Science found flaring emits five times more methane than previously thought due to flare malfunctions and inefficiencies. Analysis from Rystad Energy shows solutions to address routine flaring are overwhelmingly cost-effective and commercially available. In its supplemental proposal, EPA took incremental steps to reduce routine flaring, and EDF and other stakeholders have urged the agency to follow the lead of states like New Mexico and Colorado to eliminate emissions from routine flaring.

Strengthening the rules for flaring and limiting the conditions for when flaring is acceptable could help drive emissions down even further.

Once implemented and enforced, these combined actions will help benefit the climate while also delivering significant public health and economic benefits. Fewer methane emissions will help decrease the smog- and cancer-causing pollution that’s often emitted alongside methane — improving air quality and reducing health costs for communities who live in the oilfields. The methane mitigation industry is a multi-million dollar industry that employs thousands of people across the country, and is poised to grow larger as more operators are required to monitor and reduce methane.

Coming off yet another summer of record-breaking heat and soaring temperatures, it’s clear that reducing methane emissions across all sectors must be a climate priority in the U.S. and across the globe. EPA’s actions can represent some of the most protective methane regulations in the world and will be an example for other oil and gas producing nations.