We Can’t Expect a Reliable Energy Future Without Talking Water

This commentary originally appeared on our EDF Voices blog.

It’s no secret that electricity generation requires substantial amounts of water, and different energy sources require varying amounts of water. Nor is it a surprise that Texas and other areas in the West and Southwest are in the midst of a persistent drought. Given these realities, it is surprising that water scarcity is largely absent from the debate over which energy sources are going to be the most reliable in our energy future.

Recent media coverage has been quick to pin the challenge of reliability as one that only applies to renewables. The logic goes something like this: if the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow, we won’t have electricity, making these energy sources unreliable. But if we don’t have reliable access to abundant water resources to produce, move and manage energy that comes from water-intensive energy resources like fossil fuels, this argument against the intermittency of renewables becomes moot.

Moving forward into an uncertain energy future, the water intensity of a particular electricity source should be taken into consideration as a matter of course.

We know that solar PV and wind are virtually water-free fuel sources, and yet we continue to adopt policies that create roadblocks to their integration in favor of highly-water intensive coal and natural gas. Bringing more renewable energy onto the grid is not technologically impossible, but there are significant political and policy barriers in the way. We need to rethink how we plan for energy needs and put water in the equation from the beginning.

Water is scarce, but so too is data

While a utility generally includes water use in its permitting process to build a new power plant, actual water usage data is not consistent or current. Additionally, when analyzing water availability for power, planners should look at the situation across sectors. If they’re not considering, for example, the water needs of the agricultural sector, electric planners could have inaccurate estimates of what will be available in the future, especially in light of a changing climate. The electric sector should also be doing regular assessments of water use and needs as conditions change—heat waves, multi-year droughts, damaged infrastructure from storms and other weather events could impact water quality and quantity.

Adding Water to the Energy Equation

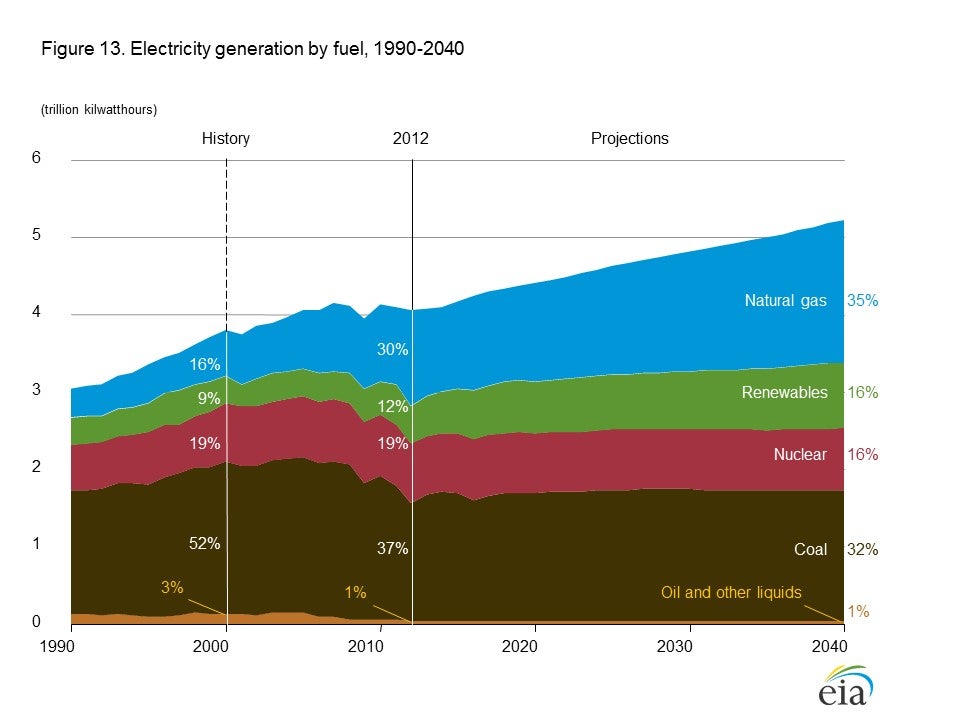

Lately there has been a lot of talk about the necessity of maintaining our current fuel mix, which is heavily dependent on fossil fuels and very water-intensive. According to the Energy Information Agency in its latest assessment, in 2012 coal accounted for 37% of U.S. electric generation, followed by natural gas (30%), nuclear (19%) and renewables (12%). Unfortunately, their predictions for the fuel mix in 2040 are not much more encouraging.

What is troubling here is that by 2040, we’re still looking at the vast majority of our electricity coming from highly water-intensive fuel sources. Where is this water supposed to come from when we are already inadequately managing our use?

Consider nuclear power: A recent NPR story on nuclear power in California highlighted the split among environmentalists over nuclear power on waste versus carbon emissions. But nowhere did the story mention the issue that will make the rest moot: if there is not enough water for highly-water intensive nuclear power to run, the low-carbon energy or the contentious waste issues are non-existent.

Water scarcity isn’t just for the West

Water scarcity has become a national issue. In the past few years, we’ve seen power implications of water shortages in areas not normally associated with water stress. During the2008 Southeastern drought as well as the 2012 drought that pummeled the Midwest, we saw shutdowns and near shutdowns of nuclear power plants in states like Alabama, North Carolina and Illinois. And let’s not forget the ongoing fight of the Tri-State Water Wars between Alabama, Georgia and Florida over distribution of increasingly scarce water for many uses, including power.

Furthermore, in its annual Winter Outlook, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts a drier and warmer winter for the Southeast (and of course continuing dry conditions in much of the West, including portions of Texas that will likely see a “redevelopment” of drought this winter).

Water Scarcity Makes Renewable Energy a Viable Option, Despite Intermittency

The intermittency of renewable energy is a red herring which can be addressed through better research, development and deployment of available technologies such as energy storage, and better policies to help integrate them into the grid. But the fact that the water usage of most renewable energy is negligible means that it is the ideal power source for our water-stressed energy future.

The discussion needs to shift. We should be talking about water intensity at the front end of our power planning because if we don’t plan with water in mind, we are planning for a dark future.