Trump’s ACE Rule May Especially Harm Vulnerable Communities

(This post was co-authored by EDF intern Laura Supple)

The Trump administration’s latest attack on clean air protections may cause the greatest harm to the most vulnerable communities – according to EPA’s own projections.

In June, the Trump administration repealed the Clean Power Plan – America’s first and only nationwide limit on carbon pollution from existing power plants – and replaced it with a pollution-enabling rule that, by EPA’s own numbers, would increase climate pollution in many states compared to no policy at all.

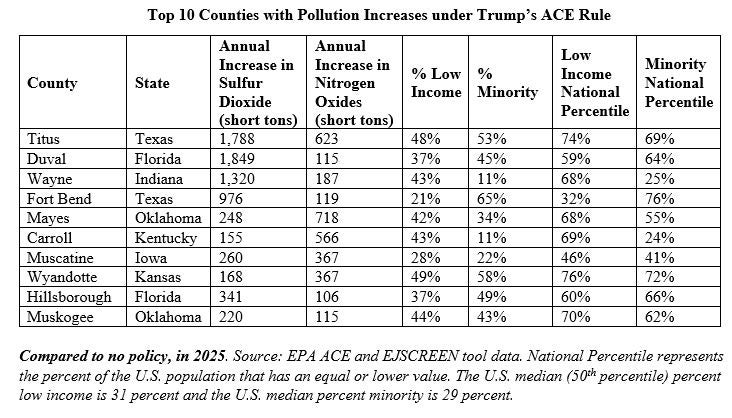

Experts have warned that under the Trump replacement, called the ACE rule, many parts of the country would also see increases in health-harming sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides pollution that lead to soot and smog. While the Administration has tried to downplay the public health consequences of the new rule, EPA’s projections show that vulnerable communities around the nation will likely suffer the most from these dangerous pollution increases.

Why would ACE have such perverse impacts? Unlike the Clean Power Plan, which sought to harness and accelerate the nation’s ongoing shift towards cleaner sources of energy, the Trump administration’s replacement instead requires states to set standards based on a narrow set of tweaks to the operating efficiency of coal plants. These “heat rate improvement” measures are not only ineffective in reducing carbon pollution, they also have the effect of incentivizing many coal plants to operate more, leading to more pollution – a phenomenon known as the “rebound effect.”

EPA’s own modeling predicts that in 2025 nearly 70 coal-fired units around the country – or roughly 17 percent of the existing coal fleet – would experience this rebound effect, producing more climate and health-harming pollution as a result of the new rule compared to “business as usual” without the rule. In most cases, the rebound effect would lead to an increase in overall pollution in the counties where these plants are located.

Of those units, roughly two-thirds are in counties (a total of 26 counties) with a disproportionate share of low-income population (defined as counties where the proportion of low-income population exceeds the national median). Of those, more than one-third are also counties where the proportion of minority population is higher than the national median.

This disproportionate burden on low-income and minority communities unlawfully flaunts EPA’s responsibility to protect human health and the environment and promote environmental justice for vulnerable communities.

Here are three examples of communities that may be most heavily affected by this new rule:

Duval County, FL

Duval County, home to the city of Jacksonville and more than 900,000 residents, is threatened by some of the most severe air pollution impacts of the Trump administration’s new rule.

In 2025, EPA projects that the county’s coal-fired units could be spewing over 1,800 additional short tons of sulfur dioxide pollution and more than 300 additional short tons of nitrogen oxide pollution compared to a no-policy baseline. In the Jacksonville area, large portions of the population already suffer from a number of respiratory illnesses, including asthma, COPD, and lung cancer, as well as heart disease. With the ACE rule in effect, the additional pollution could put the population at greater risk of these adverse health effects.

Economic inequality in Duval County exacerbates the environmental justice concerns resulting from air pollution. According to EPA’s data, the county has a 45 percent minority population (compared to a U.S. average of 38 percent) and a 37 percent low-income population (compared to a U.S. average of 34 percent). EPA ranks Duval County more diverse than where nearly two-thirds of the nation’s population lives, and lower income than where nearly 60 percent of the nation lives.

Segregation, racial income inequality, and neighborhood income inequality are all greater in Duval County than the state and national rates. For the estimated 200,000 metropolitan area residents living in poverty, the ACE rule will only exacerbate the cumulative effects of environmental pollution and social inequality.

Titus County, TX

Titus County is located between Dallas and Shreveport, Louisiana. It faces disproportionate cancer risk from airborne toxins, lower life expectancy, and higher proportions of adults reporting poor general health than the national average.

Under the ACE rule, EPA projects that in 2025 this small county’s two coal-fired units could see significant increases in generation, increasing sulfur dioxide pollution in the county by close to 1,800 short tons and nitrogen oxide by more than 600 short tons each year. Four in ten Titus County residents are Hispanic, and more than half of the residents identify as racial minorities. In addition, close to half of the county’s population is low-income. EPA ranks Titus County lower income than where at least 70 percent of the nation’s population lives and more diverse than where at least two-thirds of the nation lives.

With substantially higher racial disparities in poverty and premature death rates than the national average and limited access to health insurance or health care, Titus County’s minority and low-income communities could suffer the most from these dangerous pollution increases.

Wayne County, IN

Wayne County, located in east central Indiana on the border with Ohio, is home to close to 70,000 residents. The county already experiences a higher than average exposure to particulate matter pollution – among the top 20 percent in the nation – and a higher than average cancer prevalence.

EPA projects that in 2025, coal plant pollution in the county could increase under the ACE rule compared to a no-policy baseline, resulting in an increase of more than 1,300 short tons of sulfur dioxide pollution and close to 200 short tons of nitrogen oxide pollution.

Wayne County has a higher poverty rate than the national median. According to EPA, 43 percent of the county’s population is low-income – higher than where roughly two-thirds of the nation lives. As such, low-income communities could be disproportionately impacted under the rule.

For these vulnerable communities, the costs of the Trump administration’s ACE rule are simply too great to bear. The rule is yet another example of the Trump Administration endangering communities and failing to protect them from environmental harm.