Illustration by Kelsey King/Ensia

There’s nothing quite like biking down clogged city streets, weaving in and out of traffic. For short distances, it’s faster than driving. It’s liberating. It’s fun.

It also makes it painfully clear that most roads aren’t made for bikes. Make one mistake, and you might end up dead. If you do everything right and the 4,000-pounder next to you makes a mistake, you still might end up dead. Few regular urban cyclists remain entirely unharmed throughout the years: A broken bone (“cut off by a van”), a scraped shin (“car door”), or perhaps simply drenched on an otherwise dry road (“I avoided the mud puddle; the car didn’t”).

Blame it on my day job, but as I was cut off by yet another driver fixated on his phone while cycling to work, I got to thinking that this is how wind and solar electrons must feel as they try to navigate the electric grid. There, too, the infrastructure and rules were designed for the conventional, fossil fuel-based generators, not their smaller, greener counterparts.

We need to get off gasoline-powered vehicles, the same way we need to get off fossil-powered electricity. Biking alone, of course, can’t eliminate fossil fuel-based transportation. It’s a niche alternative that chiefly works in densely populated cities filled with environmentally concerned citizens. What works in Berkeley, Boulder, Brooklyn and Boston won’t work everywhere. Neither can trains, by the way, another favorite of environmentalists. Most U.S. cities have a lot of catching up to do with their European counterparts, but, if anything, it will be electric vehicles that will truly help us make this transition.

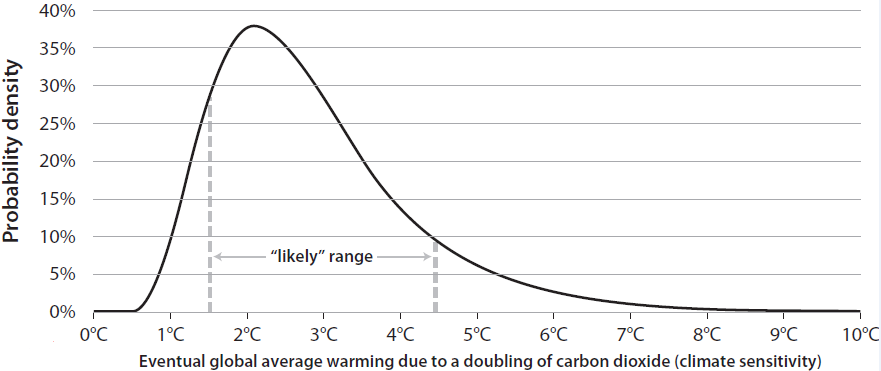

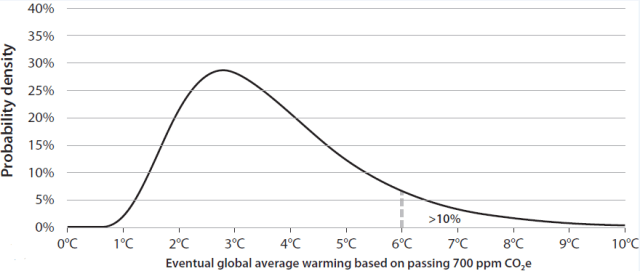

Similarly, wind and solar can’t singlehandedly eliminate fossil fuel-based electrical generation. They have great potential, much more so than biking ever will. But there, too, are limitations — chiefly the (eventual) need for storage to eliminate all fossil fuel-based generation: coal, petroleum and natural gas.

Meanwhile, there are great benefits to pushing both green technologies. Biking helps get previously sedentary drivers to move, which, in turn, extends their lives and decreases societal health care costs, assuming injuries can be avoided by appropriate bike infrastructure. Every dollar invested in that infrastructure can pay for itself many times over.

Something similar holds for subsidizing infrastructure for renewables (and, for that matter, some energy efficiency measures). The reduction in the large and risky global warming externality typically offsets the costs of subsidies and other sensible policy interventions. Many of the right policies are indeed being put in place.

Still, some traditional utilities continue to fight the integration of rooftop solar and other renewables, the way New York City did with bikes in 1987 when it tried to ban them altogether from midtown Manhattan. Today, New York is decidedly friendlier to cyclists, with Mayor Michael Bloomberg adding over 300 miles of bike lanes to city streets, and a popular, still-expanding bike share program. Renewables, for their part, are increasingly welcomed onto the grid, with increased open access and grid management tools aimed at integrating intermittent renewable energy sources. Much more needs to be done.

Getting the Job Done

There’s one more parallel that might well dwarf all else: Biking for biking’s sake is fun on a sunny Sunday afternoon. On a Monday morning, when it’s about getting to a meeting on time and looking professional, transport choice comes down to getting there reliably, quickly, cheaply and without sweat stains.

Electricity is no different. Solar panels may be an interesting, even fun, choice for some. The feeling of energy independence and doing good is a bonus. But many times, it doesn’t matter where electrons come from, just that they do — reliably, cheaply and cleanly.

The ideal policy solution for energy is as clear as it is seemingly difficult to implement: Pay the full, appropriate price for electricity at the right time and place, including currently unpriced environmental costs. Once every electron comes with the appropriate price tag, the solar panel on your roof — or the solar farm down the road — may well carry the day. Or it might not. That’s OK, too. Having the right energy mix matters more than any one technology. The energy system is a system, after all.

Biking, too, is but one form of getting around. Appropriate gas taxes, congestion charges and parking fees help incorporate the full costs of gasoline-powered engines and encourage more alternative modes of transport — from electric vehicles to public transport and bikes. Meanwhile, outright subsidizing those alternative modes is surely the right step. Pushing those alternatives at scale is as sensible as pushing renewables, especially when it also means moving closer to the ideal pricing policies in the first place.

But pushing biking or any one form of alternative transport is no end goal in itself. At the end of the day, it’s about getting from A to B. That means — as it does for energy — getting the entire system right.![]()

Published on Ensia.com on October 1st, 2015.