Roya Alkafaji, Manager, Healthy Communities and Tom Neltner, Senior Director, Safer Chemicals Initiative

We have all come to expect access to information at our fingertips. To meet this demand, water utilities are increasingly posting interactive maps online to help residents identify whether their homes are connected to lead service lines (LSLs).[1] These are the pipes that deliver water from the main under the street to homes and buildings. In homes built before 1986, this pipe could be made of lead.

With this information, people can:

- Better assess their risk of lead exposure from drinking water and take steps to reduce possible exposure (e.g., water filters);

- Make decisions when renting or purchasing a new home, and/or;

- Demand that their water utility and community invest in effective LSL replacement programs to reduce harmful exposure to lead, particularly for children who are most vulnerable.

Given the importance and growing popularity of LSL maps, we are launching a new blog series, Mapping Lead, that will explore how utilities are approaching maps, evaluate which map features are most and least effective, and share best practices to help guide future efforts.

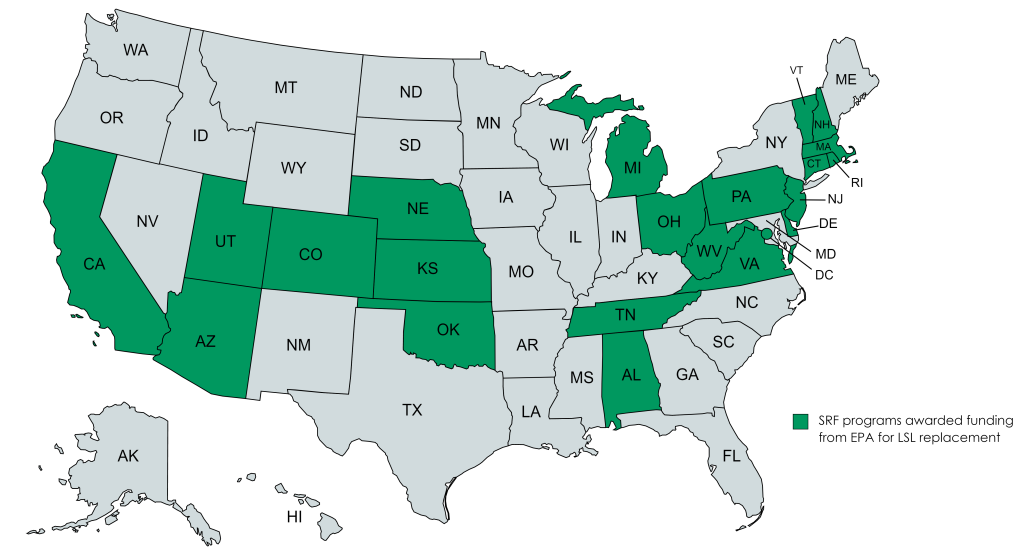

EPA recognized the value of interactive maps in its August 2022 guidance on developing service line inventories. The agency recommended utilities of all sizes consider making information available through interactive maps using commonly available tools, like GIS software. The guidance references EDF’s 2019 study for evidence of the power of these interactive maps and spotlights LSL replacement programs in Cincinnati and Denver as examples of best practices.[2]

We wholeheartedly agree with EPA’s recommendations. As a result of the agency’s guidance, we anticipate that the number of online maps is likely to grow dramatically as utilities meet an October 2024 deadline to make their inventory of service line materials publicly accessible to comply with EPA’s revised Lead and Copper Rule (LCR).

Top 100 Cities: Who Has Maps – And Who Doesn’t

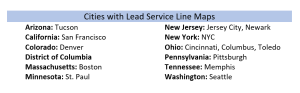

We identified over 50 interactive LSL maps that utilities have made publicly available to residents across the United States. Looking at the utilities that serve the 100 largest cities in the country, we found that 15 have LSL maps—a positive step that leverages existing asset-management tools such as GIS, while increasing public transparency. Together, these 15 utilities provide drinking water to more than 16 million people.

Throughout this blog series we’ll take a closer look at maps; in some cases, we’ll be critical of those that don’t meet the criteria for an effective map. Nonetheless, we recognize these utilities have taken a step in the right direction and should be applauded for their efforts.

We discovered that 12 large utilities were notably absent from the list of those with online maps. Given their size and location, these utilities presumably have LSLs in their distribution areas and the in-house resources to develop effective maps. We hope that by shining a light on the cities that are leading the way and addressing the contrast with those cities without maps, we can help spur action so residents of large cities served by these utilities will have access to this crucial information. For a list of the 12 utilities without maps and 15 with maps, see the tables below. We’ll continue to revise these lists as more large cities publish interactive maps online.

By the Numbers

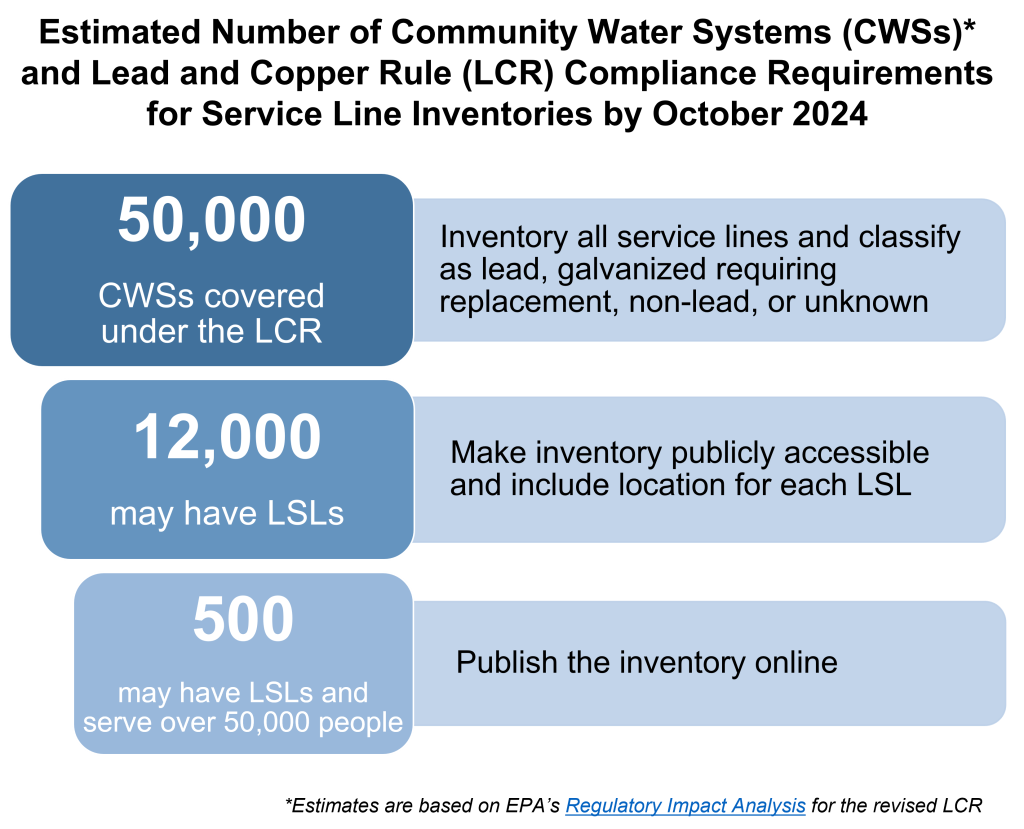

It’s important to understand the broader landscape as we track cities that are choosing interactive maps as a key tool for communicating about LSLs to the public. Using estimates from EPA’s Regulatory Impact Analysis for the revised LCR, the figure below shows the number of community water systems that fall under the purview of the LCR and subsequent requirements based on presence of LSLs and population served.

By October 2024, more than 50,000 utilities[3] will either submit an initial service line inventory or demonstrate the absence of LSLs in their distribution area.[4] EPA estimates that more than 12,000 utilities will find LSLs and thus will be required to make their inventory publicly accessible; those that serve over 50,000 people will also be required to post the inventory online.

More to Come

Follow along as we explore interactive maps and the role they play in LSL replacement.

Utilities Serving Top 100 Largest Cities With Online Interactive Maps

| Utility | Population Served† | Estimated # of LSLs‡ |

|---|---|---|

| New York City, New York (Map) | 8.3 million | 360,000 |

| Boston, Massachusetts (Map) | 2.6 million | 3,900** |

| Denver, Colorado (Map) | 1.4 million | 64,000** |

| Columbus, Ohio (Map) | 1.3 million | 28,000* |

| Seattle, Washington (Map) | 956,000 | 2,000* |

| San Francisco, California (Map) | 884,000 | 1,600* |

| Cincinnati, Ohio (Map) | 750,000 | 40,000 |

| Memphis, Tennessee (Map) | 700,000 | 14,000* |

| Tucson, Arizona (Map) | 675,000 | 600 |

| Washington, D.C. (Map) | 632,000 | 42,000** |

| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Map) | 520,000 | 16,000** |

| Toledo, Ohio (Map) | 480,000 | 30,000** |

| St. Paul, Minnesota (Map) | 400,000 | 27,000 |

| Newark, New Jersey (Map) | 295,000 | 24,000** |

| Jersey City, New Jersey (Map) | 262,000 | 16,000 |

**Active or completed LSL replacement program. The number listed reflects the estimated number of LSLs prior to the start of the program.

†Source is SDWIS, 2022.

‡Source available upon request.

Select Utilities Serving Top 100 Largest Cities That Lacked Online Interactive Maps

| Utility | Population Served† | Estimated # of LSLs‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Chicago, Illinois | 2.7 million | 380,000 |

| Baltimore, Maryland | 1.6 million | Not reported |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 1.6 million | 20,000 |

| Cleveland, Ohio | 1.3 million | 200,000 |

| Charlotte, North Carolina | 1.1 million | Not reported |

| Indianapolis, Indiana (Citizens Energy – Water) | 837,000 | 55,000-75,000 |

| Nashville, Tennessee | 722,000 | Unknown |

| Detroit, Michigan | 714,000 | 80,000 |

| Milwaukee, Wisconsin | 590,000 | 66,000 |

| Omaha, Nebraska | 554,000 | 16,000-17,000 |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 424,000 | 49,000 |

| New Orleans, Louisiana | 291,000 | Unknown |

‡Source available upon request.

[1] For this blog series, LSLs includes service lines that are “galvanized requiring replacement” per 40 CFR § 141.2.

[2] See Section 7.2 of EPA’s service line inventory guidance.

[3] For purposes of this blog series, community water suppliers as defined by EPA are referred to as utilities.

[4] Per 40 CFR 141.84(4), CWSs must categorize each service line, or portion of the service line where ownership is split, as lead, galvanized requiring replacement, non-lead, or lead status unknown. In order to declare that the system only contains non-lead service lines, this must be “determined through an evidence-based record, method, or technique.”

Revised May 2, 2023 to update blog series title and link.