Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director

The United States has made significant progress over the past fifteen years towards reducing children’s exposure to lead. While much more needs to be done to eliminate the more than $50 billion a year in societal costs from lead, the progress is good news for children since it is well known that there is no safe level of lead in children, and it can impair their brain development, contribute to learning and behavioral problems, and lower IQs.

Achieving this progress has required a diligent and ongoing commitment from all levels of government. If we expect to continue to make progress – and not backslide – the federal government needs to remain committed to reducing sources of lead exposure. So far what we’ve seen from the Trump Administration raises serious concerns about any real commitment to protecting children’s health, including from lead.

Lead has a toxic legacy from decades of extensive use in paint, gasoline, and water pipes. As long as lead is in the paint, pipes, and soil where we live, work and play, progress is far from inevitable. Protecting children from lead takes constant vigilance, especially when the paint or plumbing is disturbed. Flint provided a tragic example of what happens when we turn away. Without vigilance, the positive trends we have seen in blood lead levels could all too easily reverse course and go up. That is why the proposed cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) budget, which would eliminate the agency’s lead-based paint programs, are yet another indication that this Administration is turning its back on protecting children’s health.

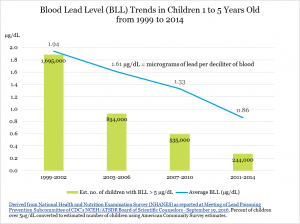

Mean blood lead levels in young children dropped 56% from 1999 to 2014

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) demonstrates that from 1999 to 2014 the levels of lead in children’s blood or “blood lead levels” (BLL) dropped preciptiously. Average BLLs in young children declined by 56% during that period with the rate of decline increasing after 2010. For children with a BLL greater than 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter (µg/dL), the reduction was an impressive 86%.

Progress result of important policy decisions

Looking at the chart above, it’s clear we’ve made significant progress in reducing children’s exposure to lead. So what happened since 1999? You can learn more about the different lead policies on EDF’s interactive tool that plots federal policy decisions and blood lead levels. Here is a quick summary of the major actions taken during this time:

- 1999 – The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) promulgated its Lead-Safe Housing Rule setting strict standards for lead-based paint in more than 1.2 million federally subsidized homes. The rule went into effect in 2000.

- 2001 – EPA promulgated hazard standards for dust and soil contaminated by lead-based paint in housing and child-occupied facilities.

- 2008 – EPA adopted its Lead Renovation, Repair and Painting (RRP) that requires lead-safe work practices by trained and certified renovators when they disturb lead-based paint in pre-1978 housing or child-occupied facilites. The rule, which went into effect in 2010, was estimated to affect more than 4.4 million projects each year.

- 2008 – EPA promulgated a National Ambient Air Quality Standard for lead that was ten-fold lower than the one set decades earlier.

- 2008 – Congress enacted the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) which set more stringent standards for lead in paint and in children’s products and required a third-party to certify that children’s products met the standards.

- 2011 – Congress lowered the definition of lead-free plumbing from 8% to 0.25% with compliance required in 2014.

- 2012 – CDC adopted a BLL Reference Level for young children that was half of its previous level of concern. That same year, Congress virtually eliminated funding for CDC’s lead office as part of its sequester cuts and has restored only part of it.

Each of these federal policy decisions had an impact in some way on the impressive drops in BLLs since 1999. And each built on earlier policy decisions banning lead from paint, gasoline, and metal food cans, and sustained investment in Lead Hazard Control Grants at HUD. There is no realistic method to assess the relative contribution of each policy change.

Progress is not inevitable – it results from sound policy and vigilance by all levels of government

Vigilance is imperative when the lead is distributed throughout our communities, whether in the estimated 37 million older homes with lead-based paint or 6.1 million with lead pipes connecting their home to the drinking water main under the street. While no renovator wants to poison a child, people usually are more careful when they are being monitored and can be held accountable. Ultimately that means people in the federal government are on-board and have the time and resources to provide the essential oversight. And the policies only work if they are updated regularly to reflect the latest scientific research.

With lead costing our society more than $50 billion annually in lost IQ points, reduced attention spans, and more violent behavior, the proposed cuts are incredibly shortsighted. The proposed cuts at EPA as well as HUD and the other agencies, if adopted by Congress, run a very real risk of slowing the progress we have seen in protecting young children from lead. The numbers could go up if we, as a nation, do not remain committed to continued progress: that means updating standards, ensuring that laws are complied with, and providing the resources federal and state agencies they need to protect children. Few areas of environmental health have such a direct and tangible feedback as levels of lead in the blood of young children.

The data is clear: policies have consequences. If members of Congress gut lead programs, their constituents will have a clear metric by which to judge the impact of their votes.

2 Comments

“I believe that the most fundamental flaw in our health care system today is its preoccupation with patching and mending and its virtual neglect of prevention and health promotion. Over half of the $700 billion we will spend this year on health care will go to treat conditions that are preventable. Yet, less than 1% of our health care budget is spent on prevention…. Lead poisoning is the number one preventable disease of children; yet only meager efforts have been undertaken to eliminate lead exposure”. Senator Thomas Harkin 1991

Well said!