When it comes to how utilities plan for future gas needs and use, challenges abound: Pipelines are built before state regulators have an opportunity to assess whether it is prudent for a gas utility to take service from that pipeline; decisions are made behind closed doors with little opportunity for stakeholder input; and planning efforts do not appropriately consider options other than traditional infrastructure such as energy efficiency, gas demand response, or renewable alternatives to natural gas.

When it comes to how utilities plan for future gas needs and use, challenges abound: Pipelines are built before state regulators have an opportunity to assess whether it is prudent for a gas utility to take service from that pipeline; decisions are made behind closed doors with little opportunity for stakeholder input; and planning efforts do not appropriately consider options other than traditional infrastructure such as energy efficiency, gas demand response, or renewable alternatives to natural gas.

Pending before the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission (RI PUC) is a proposal that would meaningfully resolve many of these issues. The utility in the state and the PUC staff crafted a joint memo proposing a more robust planning framework and rigorous oversight of utility decisions. As EDF recently explained in its comments to the RI PUC, this framework will serve the public interest and can be used as an important model for other states.

Evolving regulatory landscape

For decades, gas utilities have been planning to meet the needs of their systems and requesting cost recovery of their investments from state regulators. Such decisions were not particularly controversial and were often approved with little to no debate. These processes, however, did not contemplate the significant changes to the gas market that have arisen, particularly within the last decade.

Gas utility planning is behind the times. Rhode Island has a plan to fix it. Share on XNatural gas fired power plants are now the dominant source of electric power in the U.S. Many urban gas utilities provide more natural gas services to generators than any other customer, demonstrating that utility supply planning decisions can have significant impacts to wholesale market operations. In addition, new technologies, evolving customer expectations, and state policy and climate goals driving greenhouse gas emissions reductions are transforming gas utility decision making. But the regulatory processes and planning requirements have not evolved to keep up with these changes.

State challenges

In the absence of robust regulatory processes and planning requirements, states are faced with numerous challenges. For example, a Missouri gas utility, Spire, formed a midstream pipeline developer (Spire STL Pipeline) in order to build a 66-mile pipeline across Illinois and Missouri. Spire then committed its customers to pay approximately $600 million over the course of the twenty-year contract, and the Missouri Public Service Commission won’t review whether it was reasonable for the utility to take service from the pipeline until the pipeline is fully built. In the meantime, other neighboring pipelines will suffer as they lose customers, costs to ratepayers will increase and the region will be saddled with unneeded gas capacity.

In other states like New York, there is no required approval of long-term gas supply plans and little opportunity for interested stakeholders to provide input. Crucial information, such as the types of contracts the utilities have entered into, is shielded from the public. In some cases, the planning is so deficient, utilities have had to limit new natural gas service to manage system growth.

Utilities don’t always consider options such as energy efficiency, gas demand response or other alternatives to traditional infrastructure in their planning processes. When compared on an apples-to-apples basis, these non-traditional alternatives can provide better customer value and enhanced environmental benefits—but there is no requirement that utilities consider such alternatives.

Rhode Island model

Rhode Island has decided to tackle these issues head on. PUC Staff and the utility in the state have worked together on a set of joint recommendations for improving gas supply planning. Here are three major highlights:

- The utility’s long range plan would be subject to approval by the PUC. This means that the utility has to demonstrate before state regulators how it plans to address its supply and capacity needs over a five-year period, instead of simply making decisions in a vacuum.

- The utility would be required to seek advanced approval from the PUC for long-term customer commitments. This would avoid the problems that have arisen in Missouri, where affiliate-backed new pipelines are not reviewed until after they are built.

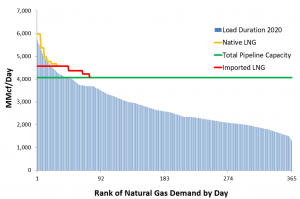

- The utility would have to provide an estimated fixed cost on a per unit basis for each of its proposed supply resources (pipeline capacity, LNG or other alternatives). This would force the company to compare alternatives on an apples-to-apples basis. As shown in the graph below, New England faces gas supply constraints approximately 20- 30 days out of the year. Solving these seasonal constraints with a pipeline solution, compared to an alternative such as LNG, would come at a significant cost to ratepayers and the environment. Requiring an estimated fixed cost on a per unit basis would help provide regulators with a clear picture of the true costs associated with each alternative.

Gas Supply Constraints in New England

New England faces gas supply constraints approximately 20- 30 days out of the year. Solving these seasonal constraints with a pipeline solution, compared to an alternative such as LNG, would come at a significant cost to ratepayers and the environment.

New England faces gas supply constraints approximately 20- 30 days out of the year. Solving these seasonal constraints with a pipeline solution, compared to an alternative such as LNG, would come at a significant cost to ratepayers and the environment.

As other states grapple with these issues, this joint planning memorandum should be viewed as an important model. As EDF recently highlighted in testimony to the New York Public Service Commission, the Rhode Island-type refinements would bring numerous benefits, including protecting customers from unreasonable financial risk, protecting the utility against after-the-fact regulatory challenges, and ensuring transparency and accountability in utility decision making.