Here we go again.

A new set of peer-reviewed scientific papers pointing to 50 percent higher than estimated regional methane emissions from oil and gas operations in Texas were published this week. And like clockwork, the oil and gas industry’s public relations machine, Energy In Depth, proclaimed that rising emissions are actually falling, and that the industry’s meager voluntary efforts are responsible.

This is, of course, wrong on both counts. In fact, it’s a willful misrepresentation of the findings.

First, the assertion that emissions are going down is flat wrong. EPA’s latest inventory released in April reports that in 2013 the oil and gas industry released more than 7.3 million metric tons of methane into the atmosphere from their operations—a three percent increase over 2012—making it the largest industrial source of methane pollution. So much for those voluntary efforts.

But EID also fumbles the two main findings of the studies: first, that traditional emissions inventories underrepresent the magnitude of the methane problem by 50 percent or more; and second, that this undercount is primarily due to relatively small but widely distributed number of sources across the region’s oil and gas supply chain, coming from leaks and equipment malfunctions not currently accounted for in the emission inventories everyone has been pointing to. In short, the Barnett papers tell us there’s a pervasive but manageable pollution problem occurring across the entire supply chain that requires a comprehensive, systematic monitoring effort and effective repair regime to address it.

Regulators in Colorado understood this to be the case, which is why Colorado took steps to adopt state-wide leak detection and repair requirements for oil and gas operations last year, and why Wyoming and Ohio have also taken first, important steps in this direction. The Barnett papers confirm the importance of these regulatory efforts and suggest that requirements to find and fix leaks across the oil and gas industry are a national priority.

The good news is that reports indicate once you find these sources, they’re fairly cheap and easy to fix. And it is important to do so. Methane is the main ingredient in natural gas and a powerful greenhouse gas and many of the leaks and malfunctions lead to emissions of other air pollutants that contribute to local air quality problems besides.

An Ounce of Prevention

Fire prevention offers a good way to think about this. Fires are relatively rare, and occur unpredictably. And just a few do real damage. But that’s an argument in FAVOR of a broad and vigilant solution: Smoke detectors in every home; regular safety inspections for large buildings; and sprinkler systems and firefighters to stop small situations from becoming big ones.

The same type of ongoing fire prevention measures keeping people safe in office buildings around the country is needed to stop this methane and associated air pollution that is harming communities near oil and gas development.

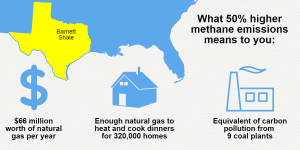

In the Barnett alone, we’re talking about a volume of methane emissions equal to $66 million per year in wasted product. Also enough gas to meet the heating and cooking needs of roughly 320,000 homes and to deliver the equivalent climate benefit of cutting emissions from nine coal plants over the next 20 years. Clearly, these are not insignificant numbers, as EID suggests. Instead, it shows how meaningless percentage points are without proper context.

Industry often points out it can be trusted to reduce methane emissions, and that regulation is not needed. But the sub-one-percent participation rate in EPA’s voluntary Natural Gas Star proves otherwise.

We don’t have any doubt that industry could manage this problem more effectively, without undue hardship or cost. But as with fire safety, there’s no evidence it will happen without proper regulations requiring every oil and gas facility to do what needs to be done, and that no one among the thousands of oil and gas producers, gatherers, or pipeline operators can derive a competitive advantage from cutting corners. Only consistent national rules can ensure that companies have a level playing field and people have the vital protections they deserve.

4 Comments

you’re both correct but EDF won’t admit that producers are reducing the amount of emissions from the wells. the plants etc are more difficult to do as there are many more places in a plant for leaks to occur. it is like whackamole close one leak at a plant and two more open up.

of real concern is that EDF wants natgas to go away just like coal, and wants only wind and solar. what you don’t want to admit is that both “renewables” require fossil fueled backups standing by in case of outages. of course those standbys have to been in operation in order to take up the slack

I just wish EDF were more honest in their reporting

Thanks Peter. We agree with you — some producers are taking responsible steps to reduce methane emissions. A 2013 University of Texas methane study found emissions during “well completion” — the process after the well is drilled and fractured — were 97 percent lower than previously estimated because many drillers used best practices as required by an EPA rule. Unfortunately, not all producers are stepping up to effectively reduce emissions in other areas, resulting in the whack-a-mole approach you describe. This is why a consistent, national policy that requires all operators to regularly check for and fix equipment leaks is so important. As you mentioned, natural gas plays and important role in balancing the intermittency of renewables with the steady need for electricity. This is why it is important to get the rules right on natural gas and ensure we are keeping more gas out of the atmosphere and in the supply chain as we shift toward a more efficient energy system.

EID did not “misrepresent” anything. In fact, the first paragraph of our post — “The findings show that methane emissions are manageable, and in the overwhelming majority of cases, leakage rates are exceedingly low” – is quite similar to what you noted above: methane leakage is manageable, and it was a “relatively small” number of sources that had high emissions.

Our difference is one of perspective and emphasis, not fact mangling. The press releases accompanying the reports, as well as this blog, all emphasized how the emissions are “50 percent higher” than what EPA’s data show. But even if we accept that premise, that doesn’t tell us much – if anything – from an environmental impact perspective. Scientists and the general public are interested in methane emissions because if the leakage rate is too high, then natural gas could lose its climate advantage. Recognizing that the leakage rate is what most folks are interested in, rather than arbitrary (and scary) comparisons between two reports, that’s what EID focused on. In this case, an average leakage rate of 1.2 percent (as Lyon et al. showed, page 8153) is well below the 3.2 percent rate that EDF has said is necessary for natural gas to keep its greenhouse gas benefits when used for electricity. It’s also comparable to other shale basins, based on recent research from NOAA and scientists in Colorado. So, yes, EID did consciously focus on the key data-driven finding of overall average emissions.

Furthermore, even if we accepted the premise that industry is “underreporting” methane leakage to EPA, then we would still see a significant decline in methane emissions since 2008, or around the time the shale gas boom began. Unless, of course, the suggestion is that EPA data *only* under-represent leakage in the most recent years, while accurately reporting it in previous years. There’s nothing to substantiate that, so the overall downward trajectory of emissions over the past 7 or so years is still a valid observation.

As I — and others from EID — have noted before, EDF deserves credit for emphasizing that this is a manageable issue. EDF is also to be commended for sticking to its pledge to focus on solutions driven by data rather than ideological advocacy, the latter of which has turned other environmental groups into hardcore anti-fracking campaigners.

In the end we have a difference in perspective, which is healthy and, in some cases, to be expected. But your claim that we “willfully misrepresented” anything is without merit (and disappointing). We merely placed emphasis on what we — and others — see as the bigger issue when it comes to methane leakage, namely the actual performance as revealed by your studies.

Steve Everley, Senior Advisor, Energy In Depth

What matters from a climate standpoint is the amount of heat-trapping pollution we’re putting into the atmosphere, and how fast we’re doing it.

It’s true that, as you note, emissions from some sources have gone down. But emissions are up from others sources, such as condensate tanks. And in many cases the standards EPA has established to control emissions from newly installed equipment, including well completions and pneumatic controllers, show how regulation is a key driver in achieving important reductions. There have been commendable actions by select companies to reduce emissions voluntarily, but not nearly on the scale needed to solve the problem.

In absolute terms, methane emissions from the oil and gas industry are simply too high – higher than they need to be, and higher than estimates using current EPA data. That’s a waste of valuable natural resources, and a serious climate problem. Research also confirms most of these emissions are completely avoidable and can be fixed at relatively little cost.

Whether or not natural gas ends up being less bad for the climate than coal – which it might very well be, at least in some cases – it’s still a challenge we can’t afford to ignore.

EID doesn’t seem to argue that methane isn’t a serious and real climate threat. Nor do you seem to disagree that it’s also a manageable issue once companies get around to it. The only question then is, how best to make that happen?

The oil and gas industry says we should rely on voluntary efforts. But there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that stewardship and good will alone will solve problem. Indeed, everything we know confirms that concrete, commonsense standards that set a level playing field for everyone involved are the best, most reliable way to bring those manageable solutions to scale.