Don’t Write Off Energy Efficiency. It’s Just About to have its Day.

By: Matt Golden, Senior Energy Finance Consultant

A few days ago, economists from the University of Chicago and the University of California, Berkeley released a study that called into question the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency. The study was based on the team’s analysis of energy savings shortfalls in the Michigan low income Weatherization Assistance Program. Since then, a host of articles have used the study’s results to call into question the value of utility-sponsored energy efficiency programs.

A few days ago, economists from the University of Chicago and the University of California, Berkeley released a study that called into question the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency. The study was based on the team’s analysis of energy savings shortfalls in the Michigan low income Weatherization Assistance Program. Since then, a host of articles have used the study’s results to call into question the value of utility-sponsored energy efficiency programs.

While this study did raise some thought-provoking points, it also contained biased assumptions and reached conclusions that far exceed its scope, lumping together market-based efficiency with low-income weatherization programs.

The report paints what can only be considered a worst case scenario. For example, it counts the costs of delivering health and safety upgrades without measuring the benefits, it assumes energy prices will never rise, and it extrapolates lessons from a publicly-funded social benefits program (designed to serve hard-to-reach citizens) to all sectors of the energy efficiency market. The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and the Illinois Institute of Technology have published good posts that explore in great detail some of the flaws in the assumptions and conclusions reached in the report.

However, this study also points to some very real and critical challenges, namely that: 1) existing models for estimating efficiency over-predict savings; 2) public programs are an expensive way to deliver services; and 3) public investments in efficiency can be valued in a number of ways producing widely varying results. The authors also correctly assert that we need to be serious about how we invest in carbon abatement, as the problem is so large we can’t afford to waste resources. Let’s unpack their conclusions.

Do energy models over-predict?

It’s fairly well known and understood that current modeling approaches over-predict baseline energy usage, and therefore the savings that result from efficiency upgrades. This is not the first study to show there is a bias toward over-prediction, especially in un-calibrated energy models. This article examines many of the core reasons why this bias exists and there are many efforts underway to correct the problem.

A better approach is to use actual energy data, not just engineering models. One recent study in New York State by Performance System Development shows that calibrating predictions to past bills dramatically improves results. California is taking a different approach with the CalTRACK system, which uses electricity meter data to track actual savings and adjust predictions to match actual performance – all while creating transparency in the marketplace.

Does efficiency have a good payback?

Measuring the cost effectiveness of an energy retrofit simply by dividing the total cost of an improvement by the savings is an oversimplified approach. Considering the host of non-energy benefits in residential retrofitting such as comfort, residential energy efficiency is put at an unfair disadvantage when we compare the full cost of a project against just the energy savings (more on this here). These issues are particularly pronounced for publicly-funded weatherization programs for low-income residents.

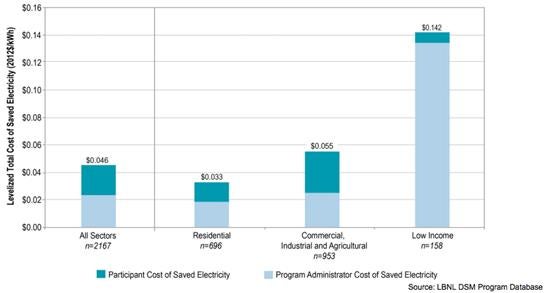

Furthermore, comparing public costs associated with low-income weatherization to market-based energy efficiency is inappropriate. Low-income weatherization is much more expensive than market-rate efficiency programs due to a host of factors, some of which were covered in the report. But in summary, compared to low-income programs, the cost of energy efficiency is much lower in market-rate sectors and public dollars are a much smaller percentage of the total investment.

Is efficiency a cost-effective way to mitigate carbon?

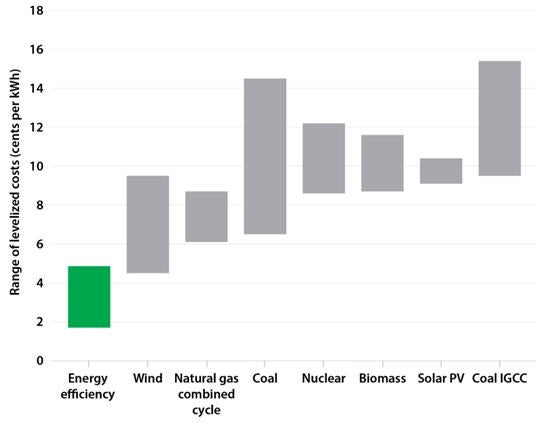

Numerous studies have calculated that the public investment in energy efficiency is more cost-effective than procuring new power sources. Even if real costs are higher than previously thought, efficiency provides a critical and immediate opportunity for large-scale emissions reductions that are cost-effective compared to other options.

The important question here is not whether public investment in efficiency is a good value, but rather, how do we maximize our efficiency returns? The energy efficiency industry is ripe with innovative business models, new types of financing, and advanced building technologies driven by a combination of access to data, engaged capital markets, and the existing and impending regulation of carbon emissions in power production. Valuing efficiency savings based on actual results will also complement a carbon price.

The takeaway should not be to give up on efficiency but to aggressively encourage innovation and experimentation that can overcome the barriers to this critical carbon-free resource.

Let’s toss the bathwater and leave the baby

Rather than pay for efficiency through engineering models and upfront rebates, we are now able to track actual energy savings at the electricity meter and pay for actual performance as it is delivered — like every other commodity and energy source. The conclusion that energy efficiency should not be a meaningful part of our country’s climate and energy solution is premature at best.

We must move away from basing efficiency investments on engineering models that incorrectly forecast energy savings, and toward investments in calculated efficiency gains based on the meter. Rather than rely on top-down programs that pay rebate coupons upfront, we should establish markets that price savings based on levelized avoided cost of new generation and pay for results as they occur, just like purchasing capacity (generated electricity from coal, natural gas, or renewable sources like solar).

By leveraging smart meter data, available tools such as the Open EE Meter, which calculates and tracks energy savings based on open standards and code, and systems such as the EDF Investor Confidence Project, which standardizes and certifies energy efficiency projects ready for investment, we can establish markets for energy savings that treat efficiency like a capacity resource. When systems are in place to standardize how reductions in energy use are measured, they can earn a real market value and help avoid building new power plants. These systems will also give investors confidence that energy efficiency projects are reliable, savings are predictable, and risk is manageable.

Power generators finance their investments based on future cash flows from selling energy, also known as project finance. If energy efficiency is going to play its part in the new utility paradigm, it’s time we start financing it like an energy infrastructure investment. Project finance for a power plant is based on the long term cash flows from selling power. When we meter energy efficiency and pay for savings as they are delivered, we turn energy efficiency into a cash flow, which can then be financed.

As this new market-based approach takes hold, utilities and program administrators will finally be able to get out of the business of figuring out how to deliver energy efficiency services through programs, and instead focus on procuring demand-side resources in much the same way they already procure capacity. In a recent California Public Utilities Commission filing, PG&E (one of California’s largest utilities) supported a pilot recommended by NRDC to test just such an approach, saying that it “has the potential to facilitate comprehensive upgrades while simultaneously minimizing implementation costs through leveraging private capital.”

With the private market taking on the risk of upfront investment in energy efficiency programs, regulators will be able to focus on protecting people and businesses through a well-regulated market structure that sends the right price signals, and leaves the business model of energy efficiency up to the private sector.

Building owners will benefit from a competitive industry incentivized to develop innovative business models and products, and the private sector will be able to invest in this critical market with the clarity of a price signal aligned with public policy goals, their bottom line, and customer demand.

Before we judge efficiency, we need to measure and value it. Doing so will allow us to treat efficiency like every other energy resource and enable market forces and competition to determine the winning solutions.

Photo source: PG&E

14 Comments

Well done Mr. Golden. A sound case all around. Thank you for your leadership and vision.

Thanks for your interest in my article!

Matt…

Thanks so much for your continuing intelligence and courage to pull back the curtains and talk about our mistaken notions about how to achieve real energy savings ( and GHC emission reductions ) through program-adopted inferential energy models and deemed savings rather than just track actual metered usage data. From the very beginning of my entering the HP/EE field, I’ve marveled at the deep-seated belief and dedication to using algorithms instead of actual usage data and have considered this as some sort of collusive obscurance through which we avoid the real numbers of whether we are getting the job done or not. Perhaps that’s too harsh, but we are after-all engaged in something that has to do with Climate Change and actual RESULTS right?. If we’re absolutely dedicated to results, then the most cost-effective means will rise to the surface and the science we develop will be proven in the field.

Thanks for your interest in my article!

I will say the same thing I said 15 years ago about energy efficiency projects…..a project must take into account that energy consumption, like any other activity, is not static but dynamic. I’m saying that proper modeling shows a decrease in the ability of any energy saving measure to offer constant savings once engaged. We found industrial and commercial customers were more amenable when we presented this rather than “this device will reduce consumption x $ over x years”

We developed a spreadsheet that showed this decrease in savings that customers could see.

Kevin Runion

Very interesting observation. If you are interested, the Investor Confidence Project (www.EEperformance.org) has an ongoing technical forum and it sounds like your experience would be constructive

Great article Matt, I couldn’t agree more. Here’s an article by Greg Thomas on his response to the Weatherization Study. http://psdconsulting.com/weatherization-residential-energy-efficiency-trial/

Thanks for your interest in my article!

Awesome article, Matt. Let the cheer-leading continue.

Do you mean that regulator-forced, utility-sponsored energy efficiency programs funded by government money to benefit low-income constituents have not achieved the predicted energy savings? I’m shocked – just shocked.

“assumes energy prices will never rise” – Yeah, that’s pretty much how you analyze any investment or loan. It also assumes that energy prices never fall either. Besides, it’s kind of a huge “red flag” if energy prices need to rise to make the numbers “pencil out”.

“there is a bias toward over-prediction” – No kidding. The predictive game-playing necessary to get project funding approved over-predicts the savings. I’m shocked – just shocked.

“a better approach is to use actual energy data, not just engineering models” – After all these years, haven’t the engineering models been upgraded by actual energy data? And perhaps I’m a bit fuzzy on this, but didn’t we use engineering models because there wasn’t actual energy data available back then? The real question seems to be: What if the actual energy data doesn’t support the investment in energy efficiency upgrades? Do we continue to flog the idea that the benefits are more than just the energy savings?

Comparing the cost of the retrofit to the cost of the energy saved puts the retrofit at an “unfair disadvantage”. Tell me, exactly, how to measure in ROI terms a resident’s “comfort”. As an investor or lender of money, tell me again how I should factor in the non-monetary benefits into my underwriting. The concept of “it’s all good” just isn’t an option in my investment modelling.

Glossing over the fact that the article has nothing to do with its title, I am perplexed by the “bathwater” analogy. Upfront rebates are what is used to pay the costs of installing EE measures. To advocate paying over time as savings are realized seems to miss that whole concept.

I have read this puff piece twice now and nothing has changed about this industry that would make me conclude that EE is “just about to have its day.” Unless the subject building meets a narrow set of criteria, it will never pencil out. And only things that pencil out get done (unless the government is involved – and even then, years later perhaps, but somebody will figure out that the government programs didn’t pencil out either).

Finally, advocating that EE be financed like Project Finance assumes that future cash flows from installing EE measures will justify the investment in EE measures. They generally don’t – that’s why this is not taking off. Of course you can probably manipulate the models to make most projects justify the investment – like the government-sponsored programs did five years ago and are now the subject of your criticism.

I think I was being pretty clear that I am not saying we should deem efficiency as the solution, any more than the authors of the study should declare it a bad idea. Instead, we should value the savings that emerge from a project correctly, and let the marketplace determine what solutions make financial sense.

Right now we compare the full cost of energy efficiency projects (both homeowner and public costs) to just the value of energy savings, even though in many (most?) cases, savings are not the primary reason customers are investing in a retrofit — known as the Total Resource Cost test. However, in private markets, public subsidies are a small percentage of the overall investment, and customers are choosing to invest their money for a variety of reasons, many of which have nothing to do with saving energy (such as comfort). If we apply the Utility Cost Test (which is a real alternative approach) we would simply compare the public cost of deploying EE to the savings delivered, which makes a lot more sense. This article unpacks this problem in more detail: http://goo.gl/5coqRH

In terms of paying for performance / project finance, there are major changes underway for how energy efficiency is deployed, being driven by a need for increased innovation, private investment, and the new availability of energy data.

Project finance does not mean that customers have to wait to get paid. Instead, we are turning portfolios of energy efficiency projects into stable cash flows. Aggregators (aka businesses) can then sell these cashflows to investors and put that money back to work in the form of a better deal for customers and contractors.

For a more detailed view of how this all can work, this article does a deeper dive: http://goo.gl/OAUtlN

While I agree with the article, the numbers on your “Levelized costs of electricity resources per kWh” chart are not clear to me.

The premise that savings are overpredicted is spot on, but then you go on to show cost effectiveness “compared to other options.” Are you showing that number as predicted number immediately after making the statement predicted numbers are over predictions, therefore showing cost effectiveness using the made up numbers you just agreed were false?

If the chart shows realization corrected numbers, it would be good to know.

Even if the the “truth adjusted” cost doubles it appears EE is still cheap. Clearly the chart becomes less impressive, but it also becomes honest – a value we really need to inject into this incredibly dishonest industry.

Green Building Advisor also has a detailed analysis of this paper, which reaches similar conclusions.

http://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/musings/gba-prime-sneak-peek-weatherization-cost-effective

Thanks for the suggestion, and for your interest – I did read this paper as part of my analysis.

I agree that a chart based on actual cost derived from usage data would provide more clarity. However, lacking that chart, I included a statement similar to what you said in your comment, that “Even if real costs are higher than previously thought, efficiency provides a critical and immediate opportunity for large-scale emissions reductions that are cost-effective compared to other options.”