David Owen asks a provocative question in the current New Yorker: If our machines use less energy, will we just use them more? He more or less says yes. The real answer comes in two parts.

For now—over days, weeks, months, and even years—energy efficiency will decrease energy use and emissions. Screw a compact fluorescent light (CFL) bulb into a socket that used to hold an incandescent and your energy use will go down. Chances are you won’t leave the lights on four times as long just because light now costs a quarter.

Over time—years, decades, centuries, and millennia—more energy efficient lights and appliances will indeed mean that more people use more of them. CFLs make light more affordable. That doesn’t matter to the typical U.S. household, where few light sockets remain unused because of energy costs. But globally—and over time—it does make a difference.

The Jevons Paradox

Owen goes back to 1865 and William Stanley Jevons who at 28 came up with what has later been called the “Jevons Paradox”:

Owen goes back to 1865 and William Stanley Jevons who at 28 came up with what has later been called the “Jevons Paradox”:

It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.

Jevons is right, of course. We have seen dramatic increases in energy efficiency over centuries while energy use has gone up by orders of magnitude.

Does that mean we shouldn’t increase energy efficiency? Of course not. We just need to be clear about what we are getting in exchange.

Energy over the millennia

By the mid-1800s, the latest and greatest in lighting technology was spermaceti, a fat from the head of sperm whales. It cost around $1,500 a barrel in today’s dollars and its price was only going to go up as whales became ever scarcer. Since then, we have seen gas lights come and go and by now electric lights cost less than a thousandth as much as the equivalent in lighting power back then.

By the mid-1800s, the latest and greatest in lighting technology was spermaceti, a fat from the head of sperm whales. It cost around $1,500 a barrel in today’s dollars and its price was only going to go up as whales became ever scarcer. Since then, we have seen gas lights come and go and by now electric lights cost less than a thousandth as much as the equivalent in lighting power back then.

That’s not a recent phenomenon. Bill Nordhaus went back to 500,000 BC. Lighting cost a million times [PDF] as much then as it does today. Needless to say, we are using much more of it now.

Another word for this phenomenon is “technological progress.” That’s really what’s behind the whale oil story, and we want more of it. There is still plenty of energy poverty [PDF] in the world. We clearly want affordable, clean energy for as many people as possible.

Of course, misguided “progress” has also led us to a planet on the brink of breakage. We need to limit greenhouse gas emissions—and do so sooner rather than later.

Will energy efficiency save the climate?

Should we look to energy efficiency as a way to do some of that? Absolutely. Energy efficiency is cheap, quick, clean, and often underutilized.

McKinsey has looked for zero-cost energy efficiency opportunities in the United States and has found possible savings of above 20 percent of total demand in 2020. Those savings, could go a long way toward meeting commonly discussed climate policy goals.

But won’t those energy savings just mean that we are using more energy eventually? History has shown it to be true after all.

In the short run—over days, weeks, months, and even years—the Jevons Paradox manifests itself in a well-documented “rebound effect” of around 10 percent. On average, you would indeed leave your CFL on for a bit longer than you would an incandescent. We lose a tenth of energy savings to increased use. (Owen cites the 10 percent figure but then goes on to overstate some of the implications dramatically.)

That leaves 90 percent in true savings and points to the clear win-win potential of energy efficiency measures.

Not by energy efficiency alone

In the long run—over years, decades, centuries, and millennia—cleaner and cheaper energy also means more people will be using more of it.

Does that mean energy efficiency is bad? Of course not. Energy inefficiency is another term for waste. And we clearly want less of that. But the problems our planet faces are too large to address through waste reduction (“reduce, reuse, recycle”) alone.

To get emissions down in the long run, there’s no escaping the (gasp) inconvenient truth that we must limit pollution directly—ideally though a declining cap on total emissions.

A cap on emissions—and the ensuing price on carbon pollution and race to invent cleaner energy sources—is the only mechanism we know that can break the link between emissions and energy use. It limits the former and makes clean energy cheaper relative to fossil fuels.

That sentence alone should occupy legal scholars for years to come. Most economists would only applaud. Getting 190-odd countries to agree on anything is extremely difficult. Unanimous consent is almost always out.

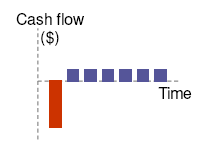

That sentence alone should occupy legal scholars for years to come. Most economists would only applaud. Getting 190-odd countries to agree on anything is extremely difficult. Unanimous consent is almost always out. First, a quick qualifier on costs. Yes, investing in low-carbon technology costs money upfront. It’s also true, though, that many investments in clean technology reap savings later.

First, a quick qualifier on costs. Yes, investing in low-carbon technology costs money upfront. It’s also true, though, that many investments in clean technology reap savings later. That still doesn’t make the transition a freebie, but it makes it much cheaper over time.

That still doesn’t make the transition a freebie, but it makes it much cheaper over time.