Clearing the Air: How New Rules for Oil & Gas Facilities Offer Major Wins for the Environment and Economy

This blog post was authored by Lauren Beatty, High Meadows Postdoctoral Economics Fellow and Aaron Wolfe, Senior Economics and Policy Analyst.

Methane pollution caused by oil and gas production in the U.S. is a major contributor to climate change and releases health-harming pollution into nearby communities. New EPA rules are projected to slash methane emissions from covered sources by 80%.

Between 2024 to 2038, EPA projects a reduction of 58 million tons of methane—equivalent to removing nearly a billion cars from the roads for a year—along with slashing 16 million tons of smog-forming volatile organic compounds (VOC) emissions and 590,000 tons of air toxics. Many of the common-sense measures in the rules will lead to economic and environmental benefits for Americans and have already been adopted by leading states and operators. They also result in capturing otherwise wasted gas. EPA estimates that by 2033, increased recovery of gas will offset $1.4 billion per year of their compliance costs.

In response to arguments from the oil and gas industry that the rules will harm operators, EDF’s Economics team analyzed the economic impacts of the regulations, including their effect on small producers, marginal wells, and consumers. We found that:

- The regulations have low compliance costs, which are further offset by profits from captured gas and are not expected to influence operational decisions by oil and gas producers;

- Marginal wells are provided significant flexibility and are not expected to face significant compliance difficulties; and

- The regulations will cause no perceivable oil and gas price increase for consumers.

Our conclusions are consistent with EPA’s own analysis and bolstered by the experience in leading states where similar methane regulations have been in effect for years without hindering production or harming the industry.

EPA’s Methane Rule

Under the EPA Methane Rule, new sources (which are typically large producers and revenue generators) must adopt EPA standards upon being drilled or built. Older, existing sources, often low-producing, marginal wells, have up to five years to comply.

EDF analysis of data from Enverus shows that the vast majority (>99%) of U.S. oil and gas sites are existing sources. While many of these wells are low-producing, studies have repeatedly shown that they are not low-emitting. Marginals wells are disproportionately high polluters, responsible for half of all methane pollution from well sites while generating just a trickle of useable product—less than 10% of U.S. oil and gas. Addressing these high-polluting, low-producing sites is critical for getting a handle on methane emissions.

The Methane Rule is cost effective

Compliance costs posed by the Methane Rule are minimal. Oil and gas producers in the United States will be required to regularly monitor their sites for leaks. They will also need to use zero-emitting technologies and may be required to make capital expenditures to retrofit existing sources with pollution control technologies. EPA thoroughly considered costs to the oil and gas industry when designing these rules, purposely aligned the implementation schedule to ease the transition. Because only newly drilled sources are subject to these rules in the first few years, there are minimal compliance costs projected until later this decade. In 2025, costs are projected to be a mere 0.02% of industry revenue, with related capital expenditures accounting for just 0.2% of total industry capital expenditures. This indicates that new sources, directly impacted by the regulations from the start, will face minimal financial hurdles, which are readily absorbed by the high production and significant revenue generated from new wells.

Marginal wells

Claims that the Methane Rule will cause thousands of lower-production wells to be shut-in or plugged are unfounded or based on a misunderstanding of the standards. Marginal wells are overwhelmingly existing sources, meaning they won’t face compliance obligations for up to five years. During that time, operators will be able to retrofit for compliance, or take advantage of federal and state funds to help close and plug end-of-life wells. EPA estimates that the annual monitoring costs for small wells will only be between $336 to $630, while it costs tens of thousands of dollars per year to operate one of these wells, meaning that compliance costs are unlikely to be a primary factor driving well closures, even for those with lower outputs.

It’s important to keep in mind that marginal wells already retire regularly, at a rate of 4-6% per year. That’s because they have reached the end of their productive lives and are no longer viable to operate. In 2022, marginal wells accounted for just 5% of total production.

While it is possible for new and modified sites to be low-producing, it is rare. According to the latest Enverus data available, there were about 400 new and modified well sites that were also low producing as of June 2023. This accounts for just 14% of all new and modified sites and less than a fraction of a percent of all well sites in the US. Moreover, on average, even these sites generate tens of thousands of dollars in revenue each year and are operated by companies that generate millions of dollars in average annual revenue.

The new regulations will not drive up prices

Industry groups argue that the increased costs of new regulations will be passed on to consumers. However, the impact of compliance costs on consumer prices is expected to be negligible. EPA’s projections suggest that the regulation’s effect on oil prices would be at most an increase of 0.33% (or 25 cents per barrel). That estimate is under the most rigid assumptions and wouldn’t even occur until 2038. The impacts on the natural gas market are projected to be at most an increase of 1.76% on prices (or 6 cents per Mcf). These minor figures are the maximum expected price increases and are even more insignificant when compared to the normal yearly price fluctuations in these markets.

For example, the standard deviation in annual prices for Henry Hub natural gas over the last decade has been $1.28 per Mcf, with the average price around $3.43 per Mcf. This shows that a 37% change in natural gas spot prices from year to year can be considered ‘typical.’ Any price increases from the regulation are expected to be imperceivable.

Leading states show that methane rules do not harm industry or production

Predicting the impact of future regulations on consumer prices, industry production, and profitability can be challenging. But examining what has happened in states with leading methane regulations can give us a better understanding.

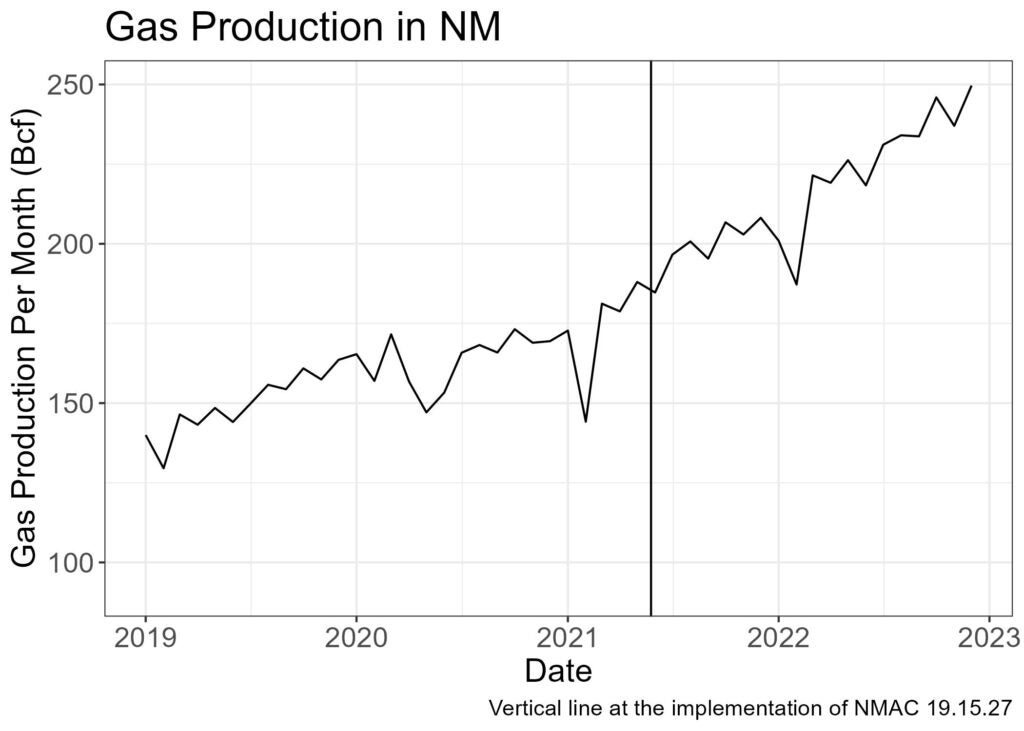

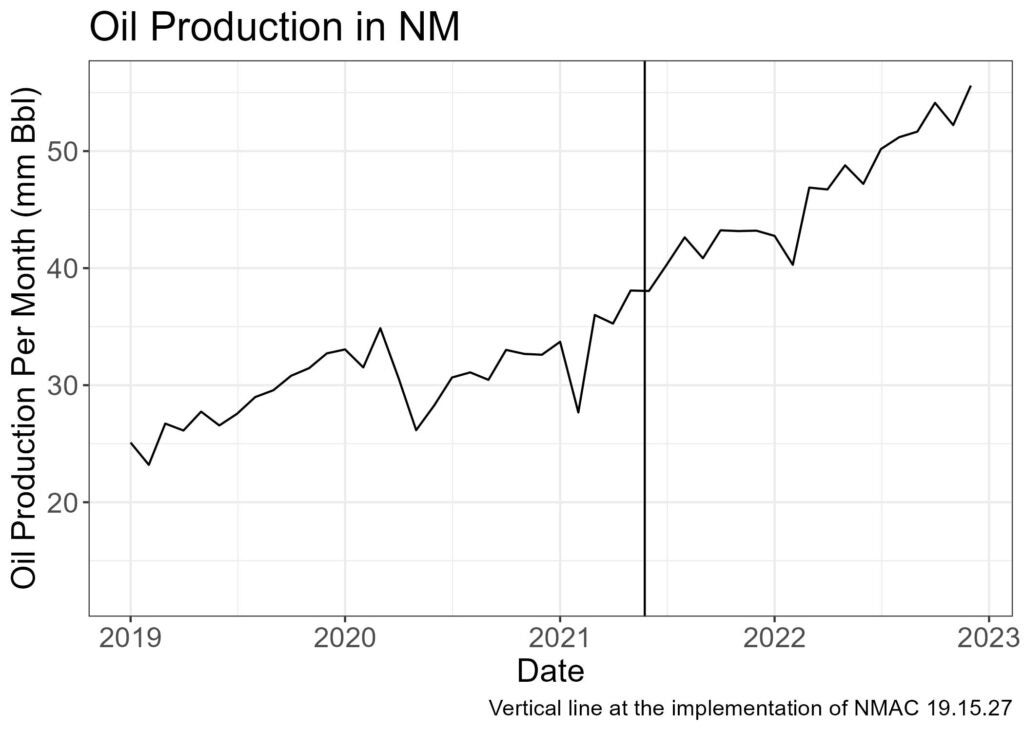

For example, back in 2021, New Mexico adopted methane rules similar to the EPA’s new ones, including flaring limitations and monitoring standards among other measures. Our analysis of oil and gas production data in New Mexico revealed these rules have had no discernible impact on the state’s production levels. Instead, as shown in the figures below, production follows a consistent upward trend preceding and after the introduction of New Mexico’s rules (marked by the vertical line) in 2021.

Conclusion

Efforts to obstruct implementation of common-sense EPA methane rules based on costs are unfounded. The EPA Methane Rules promise significant methane reductions and environmental benefits through cost-effective and common-sense standards. Moreover, the standards were designed with affordability in mind. Just as EPA found in their own analysis, we find that the rules impose modest costs while providing considerable benefits of improved climate and air quality. Attempts to impede the implementation of the Methane Rule should be opposed so that we can all enjoy the benefits of cleaner air as soon as possible.