Jobs, jobs, jobs

Co-authored with Nat Keohane.

Marc Gunther lists ten reasons why “Cancun can’t.” We won’t go into his other nine points here, but number three on the list hit home:

Environmentalists have been disingenuous about the climate issue. They’ve argued that regulation of carbon dioxide will create green jobs and grow the economy. Typical is this graphic from Environmental Defense. (“Get a step-by-step picture of how a carbon cap will spark new jobs, lift the economy and clean the air.”) Uh, no. Most economists agree that dealing with global warming will entail short term costs. (See Eric Pooley’s excellent analysis at Slate.)

Talking about jobs is one of the most difficult things to do well in the arena of climate policy. The jobs issue is highly politically charged—and for good reason, given the state of the economy. But it struck us as unfair for Marc to use EDF as his bête noire.

To begin with, the graphic that Marc links to doesn’t make the claim he ascribes to it. We weren’t saying that climate policy was a free lunch. What we were pointing out was that doing something about climate can also create good jobs in some unexpected places. More on that in a minute.

We have bent over backwards to be as balanced and rigorous as possible in our assessment of the economics of climate change.

This turns out to be perfectly illustrated by Eric Pooley’s analysis—the same one Marc links to.

Eric’s indeed excellent analysis makes two points:

First, there is a broad consensus that the cost of climate inaction would greatly exceed the cost of climate action.

That’s the main, often-forgotten point because it seems so obvious: “it’s cheaper to act than not to act.”

We should really stop here and reflect on that for a second. Many—if not most—economists do, in fact, agree on that statement and have for a while.

But that’s not our point here, either.

Small but positive

Eric’s second point concerns the cost side of the ledger. The irony here is that Eric cites our analysis as highlighting that the costs of reducing emissions will be real, but small:

Eric’s second point concerns the cost side of the ledger. The irony here is that Eric cites our analysis as highlighting that the costs of reducing emissions will be real, but small:

The second area of consensus concerns the short-term cost of climate action—the question of how expensive it will be to preserve a climate that is hospitable to humans. The Environmental Defense Fund pointed to this consensus last year when it published a study [PDF] of five nonpartisan academic and governmental economic forecasts and concluded that “the median projected impact of climate policy on U.S. GDP is less than one-half of one percent for the period 2010-2030, and under three-quarters of one percent through the middle of the century.”

That’s a mouthful.

In short, yes, the best economic studies show that there will be a cost to climate action. The costs are so small that they often fall within the general noise of model predictions, but they are there. There’s no denying that, and we never have. And yes, it was a much-cited EDF study [PDF] that makes this point, as well as a more recent update [PDF].

Just to be clear: Marc points to us as proponents of the “free lunch” theory, and then points to Eric as the best source on the costs—while Eric actually cites us as fairly and accurately surveying the available evidence on costs.

So did we contradict ourselves? Uh, no.

There is no contradiction between the following two assertions:

- There will be modest short-term economic costs associated with reducing emissions (although those will be much smaller than the economic costs of not reducing emissions!); and

- Policies to reduce emissions, like a cap-and-trade program, will lead to job creation.

“Green jobs”…

One simple reason that there’s no contradiction is that there is an important distinction between gross and net job creation.

The EDF graphic Marc links to focuses on gross job creation: investments in low-carbon energy sources and energy efficiency will create jobs.

The EDF graphic Marc links to focuses on gross job creation: investments in low-carbon energy sources and energy efficiency will create jobs.

The fact that climate policy will create jobs in some sectors is an important point in itself—simply because there have been such strong and exaggerated claims by opponents of climate policy that it will be a “job killer.” Like any major policy, comprehensive climate legislation would increase employment in some areas even as it decreased employment in others.

And jobs increases might well come in sectors where you wouldn’t expect that to happen. Consider the two examples our graphic mentioned: the labor needed to retrofit buildings to make them more energy efficient, and the 250 tons of steel needed to make a wind turbine.

So why do macro-economic models still show small positive costs to the economy?

…and economic models

First, economic models are much better at capturing changes to existing industries than the emergence of new ones. That’s not because the modelers are deliberately ignoring those new industries, but because they are, by definition, much harder to include in models of the economy—which necessarily have to be based on current and past experience.

The result is that macroeconomic models systematically miss exactly the kind of changes that would yield more employment because we are transitioning to a lower-carbon world.

There’s a more general point here as well: economic models are notoriously bad at anticipating technological innovation. For an issue like climate change, where policies are measured in decades and where technological developments will be crucial, this means that economic models are almost certain to overestimate the long-run costs of reducing emissions.

While we are at it, it’s worth pointing out that many macroeconomic models don’t actually attempt to model jobs. In fact, they generally assume full employment no matter what happens, which doesn’t leave any room for estimating increases or decreases in jobs as a result of specific policies. [Update: See our later post, “No jobs in economic modeling,” for some more nuance on this point.]

Recession economics

This leads to a fundamental point that goes to the very nature of most economic models. They assume the economy is humming along just beautifully.

These models are designed to maximize economic output given all the current assumptions around the economy. So pretty much any policy change is going to reduce GDP.

That makes sense from an economic point of view if you think that the economy is going at full speed to begin with. It clearly doesn’t make sense if the economy is stuck in a recession.

Now you want more investments precisely because you want to boost jobs and GDP.

What about jobs?

Given all these difficulties in modeling jobs, it’s hard to find a study that does this well.

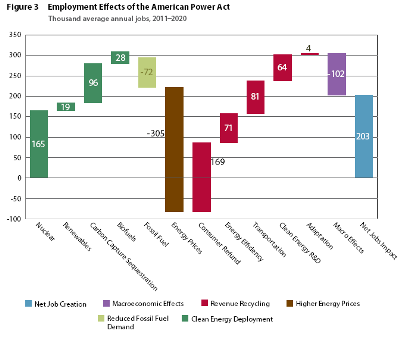

A recent Peterson Institute study by Trevor Houser, Shashank Mohan, and Ian Hoffman is one of the first to fill in the missing pieces on jobs. It comes up with a total gain of 200,000 jobs by 2020 under the American Power Act, the comprehensive energy bill debated in the Senate.

Again, we shouldn’t put our full faith into any single economic study—something our own study goes to pains to explain—so we should clearly take the specific jobs figure with a grain of salt.

But it is still instructive to look at the logic of how Houser et al. derive their number:

Macroeconomic effects and reduced demand for fossil fuels are indeed negative. Higher energy prices also decrease employment. Most of these effects, however, are compensated for by investing in energy efficiency and other clean energy measures and also by refunding money back to consumers directly. These kinds of refunds were central to the Waxman-Markey bill that passed the House in 2009 as well as the legislation considered in the Senate.

Peterson adds another important category largely missing in most macro models: clean energy deployment—the low-carbon technologies that a transition to cleaner forms of energy generation would spur.

Small costs, large benefits

Will a transition to a clean energy future be a free lunch? No, there will be costs—small and manageable costs, but still costs. No pain no gain.

The answer to the employment question is a bit less clear. The Peterson Institute study is worth a look: 200,000 additional jobs by 2020 matters to those employees, but, first, it’s only one study, and, more importantly, it’s negligibly small when compared to today’s U.S. labor force in the order of 130 million employees.

Pending further studies, by far the best estimate for overall employment effects of any sensible climate policy is zero. Some dirty, old industries will lose. Clean, new industries will gain.

In the end, though, we cannot talk about any of this without returning to point #1: The costs of not acting dwarf the costs of any sensible climate policy. Environmental groups have been saying that for years, and we won’t apologize for that.

One Comment

Thanks for this response. I agree with your economic analysis.

I probably should not have singled out Environmental Defense as a proponent of the “green jobs” argument. I did so because I remembered TV commercials like the one from EDF featuring the mayor of a Pennsylvania town saying that”Carbon Caps = Hard Hats.” That certainly left viewers with the impression that cap-and-trade is a jobs creation program.

See this http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hM7Xw_kaRIQ

But I understand that it’s hard to make nuanced arguments about economy in a 30-second commercial. And I do appreciate the hard and serious work that you (Gernot and Nat) have done to educate the interested public about how cap-and-trade should work. Certainly you have been more honest and fair that critics who demonize carbon regulation as a jobs killer.