Latest available national data shows increase in blood lead levels for at least 2 million kids

Tom Neltner, J.D., Chemicals Policy Director

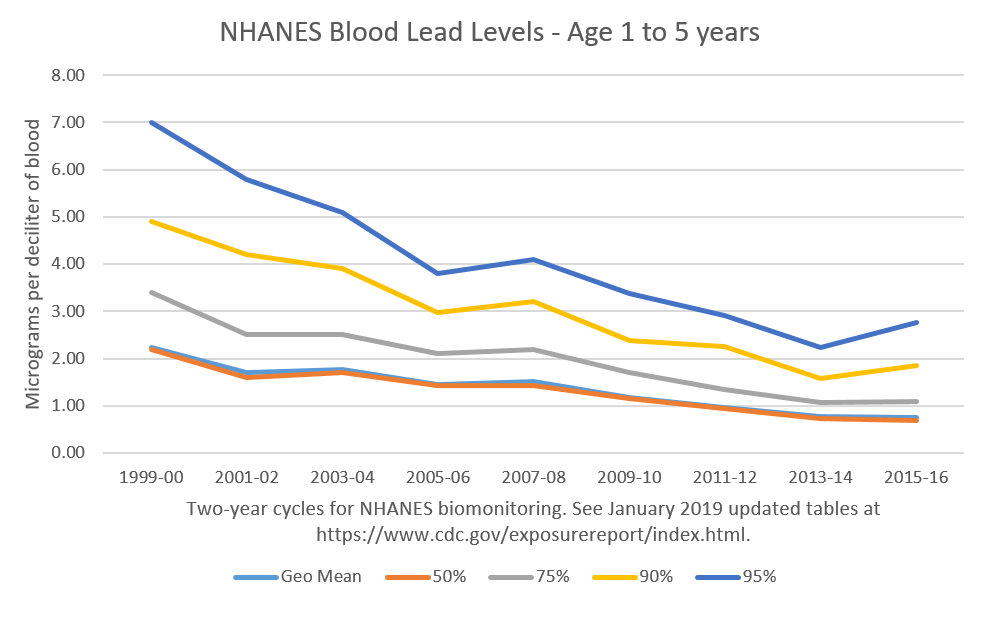

In February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a report summarizing the biomonitoring data from its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Given EDF’s focus on protecting children from lead exposure, we went straight to the most recent blood lead monitoring results. The results are disturbing. As shown in Figure 1 below, after years of progress, in 2015-16 the blood lead levels (BLLs) of more than 2 million young children[1] increased:

- Average child BLL: 48% BLL decrease from 2007-8 to 2013-14 but only a 3% decrease in 2015-16.

- 75th percentile BLL (75% of children are below this level): 51% decrease from 2007-8 to 2013-14 but a 2% increase in 2015-16.

- 90th percentile BLL: 51% decrease from 2007-8 to 2013-14 but an 18% increase in 2015-16.

- 95th percentile BLL: 45% decrease from 2007-8 to 2013-14 but a 23% increase in 2015-16.

As with the smaller uptick in 2007-08 (which may have been related to the housing crises), it may only be short-term setback, nonetheless it bears careful examination.

Even more disturbing is the Trump Administration’s response to this information. The Administration:

- Ignored the data in the rosy picture of progress it painted in its recent Lead Action Plan; and

- Appears to be repeating mistakes of the past by proposing to slash CDC’s childhood lead poisoning prevention budget in half.

Why is the NHANES data important?

NHANES is an ongoing survey assessing the health and nutritional status of a nationally representative sample of about 8,000 children and adults in the United States. The survey includes a biomonitoring study of blood and urine samples to provide national estimates of the population’s exposure to more than 300 chemicals that may result from environmental exposures.

CDC uses the blood lead levels from about 1,000 one-to-five year old children tested every two years to track progress in reducing blood lead levels. The agency’s childhood lead poisoning prevention program (CLPPP) uses the data to adjust federal priorities and identify potential problems. The data also serves as a benchmark that CDC and other federal agencies use to measure progress toward their shared goal of eliminating elevated blood lead levels in children.

Administration ignored the data in its recent Lead Action Plan and EPA’s Status Report

On December 20, 2018, days before the shutdown, the 17 agencies that make up the President’s Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children released the “Federal Action Plan to Reduce Childhood Lead Exposure and Associated Health Impacts.” The Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) chair the Task Force. In our blog, we described the Plan as a “missed opportunity to protect kids from lead” because it fell far short of the promises made, lacked clear goals and objectives, and did not address funding needs.

The Plan painted a rosy picture of the progress made in reducing children’s exposure to lead. It described the average blood lead levels dropping twenty-fold and the 95th percentile levels dropping 12-fold from 1976-80 to 2013-14. We thought it was odd that the report did not include the NHANES data from 2015-16 — which were publicly available.

But the failure to consider the disturbing data continued when EPA released its “Implementation Status Report” on April 1 touting its accomplishments in reducing children’s exposure to lead. The report makes no mention of the NHANES results for 2015-16 even though the agency had the data and could point to the February CDC report.

Repeating past mistakes by proposing to slash CDC’s childhood lead poisoning prevention grants

While there’s no way to know for sure why we saw this reversal on blood lead levels in 2015-16, we believe that the budget cuts to CDC’s CLPPP from 2012 to 2014 under the Obama Administration may have played a major role. These cuts eliminated grants to state and local health department programs and left only enough funds for CDC to serve as a caretaker.

Though the grants of about $32 million a year were a small proportion of CDC’s annual budget of $11.2 billion, they were critical to support programs across the country. As the grants ended, state and local lead poisoning prevention programs started shutting down or drastically reducing their work. This was the case in Michigan and likely explained in part why the state health department was slow to react to the tragedy in Flint, where it was left to Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at a local clinic, to recognize the problem. Only a few states, including New York, had sufficient other sources of funds to continue efforts, albeit in a scaled down manner.

As shown in Table 1, in 2014, Congress restored the CDC CLPPP funding. While state and local programs ramped up their efforts, there is no question that momentum was lost when the funding was cut. And staff hiring was slow.

Table 1: CDC’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Budget – Requested and Appropriated

| Federal Fiscal Year | Administration Request | Congress Appropriated |

|---|---|---|

| FY2011 | $30.7 million* | $35.0 million |

| FY2012 | $2.0 million* | $2.5 million |

| FY2013 | $2.0 million* | $2.3 million |

| FY2014 | $5.0 million* | $28.5 million |

| FY2015 | $28.5 million* | $28.5 million |

| FY2016 | $28.5 million* | $34.0 million |

| FY2017 | $31.5 million* | $34.0 million |

| FY2018 | $17 million | $34.9 million |

| FY2019 | $17 million | $35.0 million |

| FY2020 | $17 million | |

| * indicates Obama Administration. | ||

The Obama Administration’s cuts to CDC CLPPP budget were a mistake that took years for local and state programs to recover from. The cuts may also be responsible for the reversal in the NHANES data. Congress should never have acquiesced, but in the budget cutting frenzy of those years, they agreed. As a result, our country lost one of its most valuable tools to ensure children at high-risk for lead exposure are identified and protected and to spot emerging regional or local problems.

With the NHANES data readily available, we expected that the Trump Administration would not make the same mistake. However, in its proposed 2020 budget for CDC, the Trump Administration once again asked Congress to slash CDC’s CLPPP from its current $35 million to $17 million with grants to state and local health departments bearing almost all of the cut. In the proposed budgets for the prior two years, the Trump Administration proposed similar cuts, and Congress ignored the request and kept funding relatively steady. We hope that it will do the same for the current round of appropriations.

Progress takes vigilance to protect kids from lead

As we noted two years ago in a blog on the Administration’s proposed budget cuts, as long as children live in homes with lead-based paint and lead pipes, we will need continued vigilance and ongoing investment in programs that protect children. We can’t afford to let children’s lead exposure increase — we know the consequences.

[1] There are 20 million 1-5 year old children. 10% of these are in the 90th percentile.