EPA should ensure federal funds do not support harmful partial LSL replacements

Tom Neltner, Senior Director, Safer Chemicals Initiative and Roya Alkafaji, Manager, Healthy Communities

Last year, the White House set a goal of eliminating lead service lines (LSLs) by 2032 and worked with Congress to enact the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)—also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law—which included critical resources to help meet this goal.

Through IIJA, communities across the United States have access to federal funds to replace an estimated 9 million LSLs, which are the pipes that connect homes to water mains under the street. EDF fully supports the President’s goal and related efforts to protect public health and advance environmental justice.

EPA is off to a good start. The agency:

- Distributed the first of five years of IIJA funds to state revolving fund (SRF) programs, including $15 billion dedicated to LSL replacement and $11.7 billion in general funding for drinking water infrastructure projects (which may also be used for LSL replacement).

- Provided guidance to states to help ensure the funds go to “disadvantaged communities” and that the $15 billion is used for full (not partial) replacements.

- Plans to publish the results of its drinking water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment. That report is crucial to updating the formula by which SRF funds will be allocated to states in subsequent years.

However, as states begin to administer SRF funds from the $11.7 billion in general infrastructure funding, EPA’s lack of clarity on what the funds can and cannot be used for reveals problems. Specifically, some states may allow this funding to pay for partial – as opposed to full – LSL replacements when a utility works on aging water mains that have LSLs attached to them.

While this has been allowed under the federal Lead and Copper Rule, the practice is inconsistent with recent EPA guidelines and federal goals. Specifically, the practice raises four serious concerns:

- Health risks: Disturbance of LSLs releases lead into the drinking water. With partial LSL replacements, residents have significantly increased risk of exposure to lead without the long-term benefit of full replacement. And when the remainder of the line is replaced in the future, they are at risk – albeit a much lower one – of exposure again. [1]

- Civil rights violations: Customers who are expected to pay to replace the portion of the LSL running from the property line to their house may not be able to afford the cost when the utility comes down their street. They are then left with little choice but to accept higher risk of lead exposure because of partial replacements. This can result in discrimination against low-income communities of color, which is prohibited by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 if the entity receives any federal funds. EPA is currently investigating this situation against Providence Water.

- NEPA violation: In order to comply with EPA’s regulation for the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a state must determine that partial LSL replacements do not “have disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on any community, including minority communities, low-income communities, or federally recognized Indian tribal communities”. [2]

- Waste of limited funding: When you have already dug up the street to replace a water main, fully replacing attached LSLs at the same time is the most efficient use of taxpayer money. Indiana American Water and others have demonstrated that you can reduce the cost of LSL replacement by 25% or more by replacing the full line in one visit.

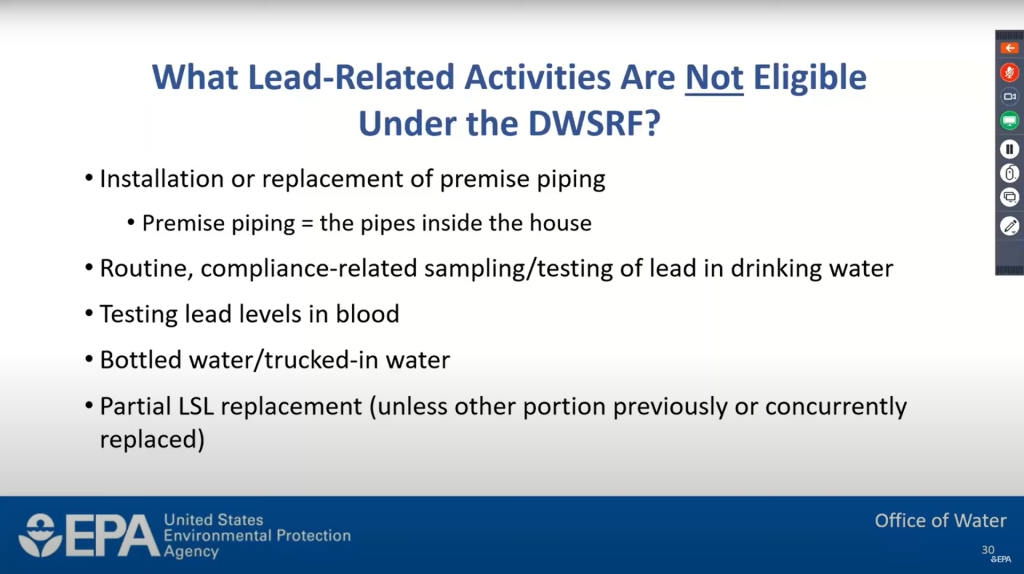

In an August webinar, EPA explained that “partial LSL replacement (unless other portion previously or concurrently replaced)” is not eligible for funding under the Drinking Water SRF as a lead-related activity. Presumably, replacing a water main with LSLs attached to it would disturb the pipes and therefore be considered a lead-related activity. But without clear guidance from EPA, states are at risk of incorrectly administering federal funding and failing to comply with NEPA and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

State agencies that manage SRFs are central to tackling lead in drinking water as they develop intended use plans and project priority lists. It is critical that state agencies have the tools and guidance they need to review and approve utility project proposals that focus on protecting public health, maximizing the impact of federal funds, and meeting all federal requirements.

To achieve the White House’s goal, EPA needs to ensure that states are in compliance with federal laws and have the guidance they need to approve effective, equitable projects.

[1] Under 40 CFR 141.85(f), when a lead service line is disturbed, EPA requires that systems provide the customer with “information about the potential for elevated lead levels in drinking water as a result of the disturbance as well as instructions for a flushing procedure to remove particulate lead.”

[2] A disproportionately high and adverse human health effect on any community would be an extraordinary circumstance that means the grant does not qualify for a categorical exclusion from the requirement for an environmental assessment at 40 C.F.R. § 6.204.