NEPA requires water utilities to evaluate potential discriminatory effects before starting work that disturbs lead pipes

Tom Neltner, Senior Director, Safer Chemicals Initiative; and Jennifer Ortega, Research Analyst

Providence Water, Rhode Island’s largest water utility, has applied for state funds to rehabilitate drinking water mains in its service area. Lead service lines (LSLs) are often attached to the mains and carry drinking water to customer’s homes. The utility has requested a “categorical exclusion” from the basic environmental assessment requirement for projects seeking money from the State Revolving Loan Fund (SRF). We believe the exclusion is not appropriate and have sent a letter to the Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) asking it to deny Providence Water’s request.

As part of its work, Providence Water apparently plans to replace LSLs on public property and give customers the option to accept a 10-year interest free loan to replace the LSLs that run under their private property. However, this practice forces customers to choose between paying for a full LSL replacement or risking greater lead exposure from the disturbance caused by a partial LSL replacement. It is also the basis of a civil rights complaint that Childhood Lead Action Project (CLAP), South Providence Neighborhood Association, Direct Action for Rights and Equality, National Center for Healthy Housing, and EDF filed with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in January.

EPA, which allocates grants to SRF programs has begun to investigate the civil rights issues raised by the complaint, which demonstrated that Providence Water’s practices disproportionately and adversely affect the health of low-income, Black, Latinx, and Native American residents by increasing their risk of exposure to lead in drinking water.

Under federal and state National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations, SRF projects are not eligible for a categorical exclusion where an “extraordinary circumstance” is present. The discriminatory effects of Providence Water’s LSL replacement practices represent such a circumstance, and the utility should not be eligible for a categorical exclusion unless it changes its LSL replacement practices.

In our letter, we asked that RIDOH direct Providence Water to either:

- Demonstrate that its planned rehabilitation work and the partial LSL replacements that result will not disproportionately and adversely affect the health of low-income, Black, Latinx, and Native American residents; or

- Revise its practices to ensure the disproportionate impacts from the increased risk of lead exposure do not occur, by requiring the utility to conduct full LSL replacements, with costs shared equitably among all rate payers or, better, by using federal funds made available through the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

More broadly, water utilities should consider the potential for discriminatory health effects whenever they plan to rehabilitate a water main connected to LSLs and expect customers to pay to replace any part of the LSL. State SRF programs should not grant categorical exclusions from the NEPA-related requirements without an evaluation or without requiring a utility to conduct one.

What is NEPA and why does it apply to state SRF decisions?

NEPA is a federal environmental law that applies broadly to federal agencies and their actions. It is designed to ensure that environmental impacts are explicitly considered in the decision-making process through the use of environmental assessments.

EPA provides funds to states for the SRF program, and the state in turn must demonstrate it has procedures in place that are consistent with NEPA.

Typically, utilities applying for funding must conduct an environmental assessment to determine if a proposed action may cause significant environmental effects. However, an assessment is not required if the project is covered by a “categorical exclusion.” Water main rehabilitation and replacement work generally qualify for such an exclusion and utilities typically claim the exclusion in SRF applications. See 40 C.F.R. § 6.204.

However, a categorical exclusion does not apply where an “extraordinary circumstance” is present. EPA’s regulations describe ten extraordinary circumstances ranging from a significant effect on land use patterns, to adverse air quality effects, to disproportionate health effects.

Disproportionate health effects qualify as an extraordinary circumstance where:

The proposed action is known or expected to have disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on any community, including minority communities, low-income communities, or federally-recognized Indian tribal communities.

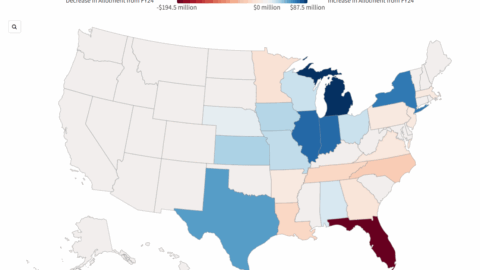

We maintain that SRF programs must not grant a categorical exclusion for projects rehabilitating water mains attached to LSLs without an evaluation of the disproportionate health effects on low-income communities and communities of color that may result if customers are expected to pay for a full LSL replacement. This is particularly important with the influx of more than $11 billion in base SRF funding to states from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The simplest option to avoid potential discrimination is to require utilities to cover all reasonable costs of LSL replacements.