Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director and Maricel Maffini, Ph.D., Consultant

It has been more than 18 months since EDF and other advocates challenged the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) May 2017 decision to continue allowing perchlorate in dry food plastic packaging and food handling equipment.

While Congress gives FDA 180 days to act on food additive petitions, FDA must act “as soon as possible” on a challenge such as ours. However, the agency has yet to complete a review of its May 2017 decision in light of our concerns and evaluate whether to either stand by it, or reverse it. We did not expect FDA would take three times longer to review a decision already made, especially since our objection is largely based on the agency’s own data.

In the meantime, perchlorate in food continues to threaten children’s brains. The chemical, a component of rocket fuel, disrupts the thyroid gland’s normal function and reduces production of the thyroid hormone needed for healthy fetal and child brain development. FDA’s own studies show increased levels of perchlorate in foods such as baby food dry cereal, indicating the chemical’s intentional use in dry food packaging is the likely source of increased exposure for young children.

How FDA got it wrong

In FDA’s May 2017 decision to continue allowing intentional use of perchlorate in contact with dry food, the agency largely relied on flawed science to assess dietary exposure. Its three central errors were:

- Ignoring its own data showing significantly increased exposure for children;

- Woefully underestimating exposure based on a flawed migration test; and

- Unrealistically assuming that perchlorate-laden plastic would only contact food once.

Below, we take an in-depth look at the three major mistakes FDA made in its decision to continue allowing perchlorate in food – and why it’s critical for the agency to take action on the chemical now.

- FDA ignored its own data showing significantly increased exposure for children

In its decision, FDA made no reference to a study published five months earlier by its own scientists describing the perchlorate concentrations in food collected by its Total Diet Study (TDS) from 2008 to 2012. The study evaluated the dietary intake of perchlorate by various age groups, including an assessment of the relative contribution from 12 different food types to each age group. It also compared the results from 2008-2012 to an earlier TDS study of foods collected from 2003 to 2006.

While not highlighted in the study, the data revealed a stunning increase in young children’s mean dietary intake of perchlorate in 2008-2012 as compared to 2003-2006.[1]

Specifically, the median dietary intake increased 34% for children 6 to 11 months; 23% for 2-year-olds; and 12% for 6-year-olds. Older children and adults did not show an increase, indicating that foods eaten by children six or younger had higher concentrations of perchlorate than foods favored by adults.

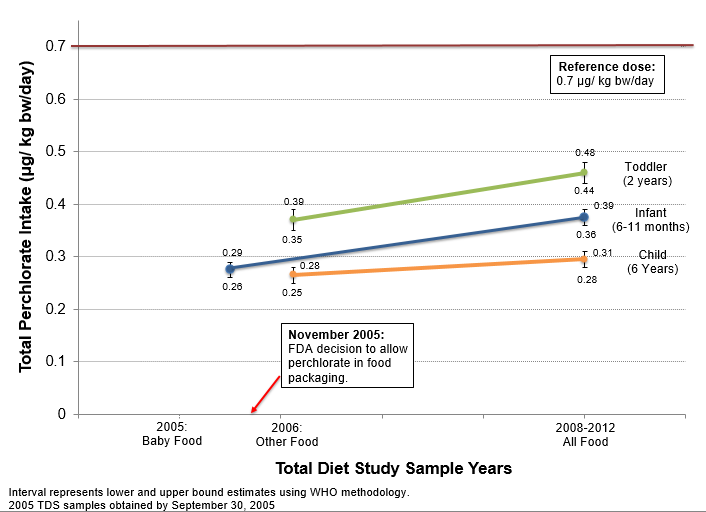

Despite dates of 2003-2006, FDA actually collected all of the baby food used in that study prior to the agency’s November 2005 decision to approve perchlorate’s use in dry food packaging and food handling equipment. This is significant because it allows a clear comparison of perchlorate levels in food before and after FDA’s decision. Figure 1 provides the information graphically.

Figure 1: Increase in perchlorate intake in young children after FDA’s approval of perchlorate use in dry food packaging and handling equipment.

For these children, FDA estimated dietary perchlorate intake in 2008-2012 using two different methods[2] and compared them to the safe dose (also known as the reference dose) set in 2005 by the National Research Council (NRC). It is important to note that the safe dose is significantly outdated; it was established before the science showing the risks of irreversible disruption to brain development was well understood, and is currently under review by the Environmental Protection Agency.

FDA saw no cause for concern even when the upper range of exposures approached the outdated safe dose using the Word Health Organization (WHO) statistical method (as shown in Figure 1). However, the results were even more disturbing when FDA applied to the same data a newer method its scientists developed to estimate exposure: for 2 year-olds, the estimated upper range of exposure to perchlorate was greater than the outdated safe dose, and for 6 to 11 month-olds, the estimate was almost equal.

At the time of its decision in May 2017, FDA also updated its perchlorate webpage to provide the results of its study and the data from the 2008-2012 TDS. Rather than explain the increased dietary intake for young children, FDA glossed over the estimated dietary intake findings, focusing instead on the perchlorate average in all food types.

In our challenge to FDA’s decision, we dug deeper into FDA’s TDS data and focused on dry cereal samples designated by the agency as baby food.[3] We chose these samples because:

- Dry cereal was unlikely to be contaminated by other sources of perchlorate such as degraded hypochlorite bleach or water contaminated from industrial sites.

- The samples designated by FDA as baby food provided a clear before-and-after approval example.

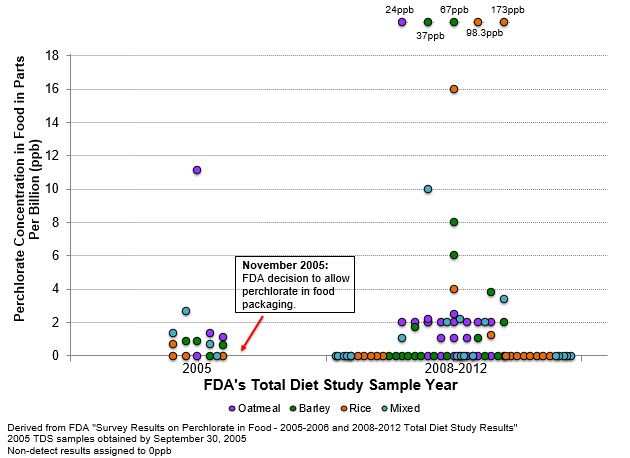

Figure 2 provides the results.

Figure 2: Perchlorate concentration increased in four baby food dry cereals collected 3-7 years after FDA approval.

Bulk raw material packaging, known as Super Sacks in the industry, is one of the advertised uses of the perchlorate-laden packaging. This distribution is what we would expect to see if the perchlorate-laden bulk packaging was used only by some but not all grain suppliers.

The percent of baby food dry cereal samples with detectable levels of perchlorate increased from 5% to 15%. Most significantly, six of the highest levels were far greater than the maximum level of 11 parts per billion (ppb) found before its approval. One post-approval sample, a baby food dry rice cereal, had 173 ppb.[4]

By focusing on all the foods, FDA missed the real story behind the data – since 2005, young children’s food has contained increased amounts of perchlorate.

- FDA woefully underestimated exposure based on flawed migration testing

Critical steps in evaluating whether the uses of food contact substances are safe include determining (1) how much is likely to migrate into food from that use, and (2) how many opportunities there are for that migration to occur.

Historically, FDA assumes that there will be virtually no migration from food contact substances into dry food, an assumption that’s not scientifically defensible.[5] Therefore, in 2005, when Ciba Specialty Chemicals requested FDA’s approval of its perchlorate-laden plastic to use in contact with food, it relied on the agency’s assumption.

A decade later, BASF, which bought Ciba Specialty Chemicals, agreed to conduct migration tests to address questions raised by a food additive petition from health advocates requesting FDA reconsider its perchlorate approval.

BASF submitted the migration test results to FDA in November 2015. The test results revealed both how little FDA understood about the uses it had approved, and how significant the potential migration may be.

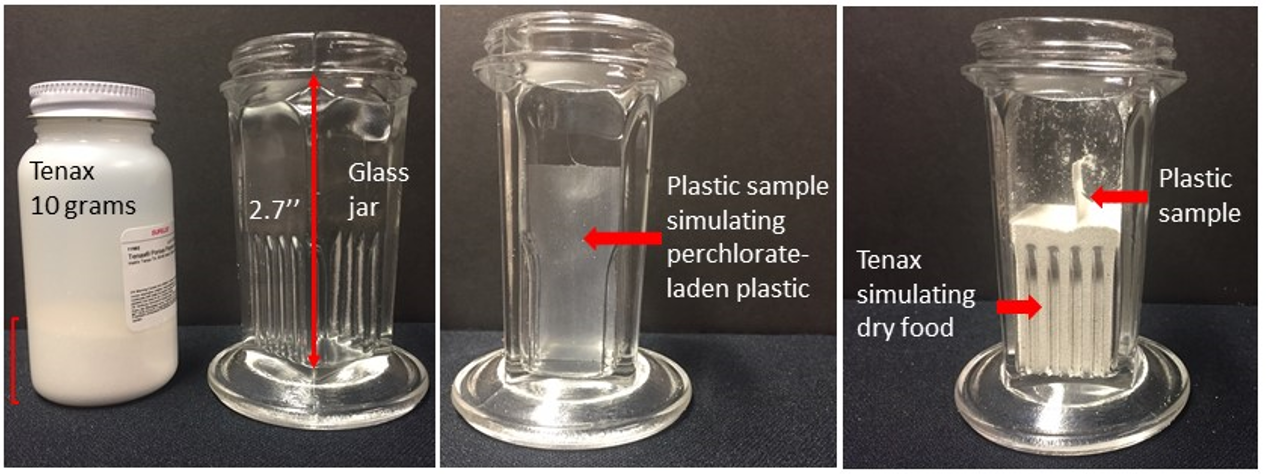

FDA and BASF agreed upon the following test to figure out whether perchlorate will migrate from plastic to dry food. Four square inches of perchlorate-laden plastic was inserted into a glass jar roughly 1” by 1” wide by 2.7” tall. To simulate dry food, 12 grams of a dry powder called Tenax (with the consistency of flour) was poured into the jar. The study allowed the plastic to contact the Tenax for 2, 24, 96, and 240 hours. After the appropriate time had passed, the plastic was removed, and the Tenax was analyzed for perchlorate. The photos below show the glass jar, Tenax, and a representation of the migration test.

Figure 3. Representation of the migration test based on BASF’s description

For each of the four time periods, perchlorate was detected in the Tenax but at levels below which the amount could be accurately quantified. BASF stated that the results suggested “that the perchlorate found in the simulant [Tenax] was most likely caused by surface abrasion.”

And therein lies the problem. The test was not designed to measure abrasion, but rather how much of the chemical leached into or was absorbed by the Tenax. As such, the test bears little resemblance to the actual uses of perchlorate-laden plastic.

The primary purpose of adding perchlorate to plastic food packaging is to reduce the static charge that builds up when a dry food flows across plastic. These are the same circumstance likely to result in abrasion.[6]

In 2014, we found a brochure from BASF for Irgastat P18, the trade name for the perchlorate-laden plastic, promoting its use in China and stating, “The product is approved and used for bulk and industrial food and non-food contact packaging.” Neither the sales brochure nor a technical product flyer mentioned the presence of perchlorate in Irgastat P18. We also found a 2004 patent application proposing use of Irgastat P18 as a liner in flexible bulk packaging commonly known as Super Sacks.

While there are many alternative ways to prevent or manage static charges, the company sought to add perchlorate as a new option. Below is a photo of a typical Super Sack.

Figure 4. Super Sack filled with solid material. The arrow indicates the point of entry of the material

In a Super Sack, a ton of dry food such as rice or corn meal is poured into the top and later emptied from an opening in the bottom. The solids enter and leave at high velocity and may generate static buildup in a standard plastic. These high velocities may also abrade the plastic.

The amount of abrasion, and resulting perchlorate migration, likely to be seen from a Super Sack use bears no resemblance to the migration test that BASF used with FDA’s approval – in which the jar with the perchlorate laden plastic and Tenax sat quietly undisturbed on a shelf in a warm environment.

Despite having only two dynamic contacts with Tenax, namely when the soft powder was poured onto the plastic placed in the jar and at the end of the experiment when the plastic was removed from the jar, BASF reported abrasion as the possible explanation for the small amounts of perchlorate that migrated into the Tenax.

In contrast, an Irgastat P18 liner used in real-world conditions would experience much, much more abrasion during a single use from most dry foods than BASF found in its poorly designed migration test.

We pointed out the flaws of the migration test to FDA, but the agency largely based its denial of our petition on the test results asserting that the levels found are so low that it won’t cause any health concern.

- FDA unrealistically assumed that perchlorate-laden plastic would only contact food once

The third critical flaw is that FDA assumed food would have only a single contact with perchlorate-laden plastic. However, the description of FDA’s approval of perchlorate used in plastic material allows dry food to contact said material multiple times.

In today’s global food supply, perchlorate-laden plastic packaging used to move food from farm and factory to the grocery store will contact dry food ingredients and food additives many times — adding more perchlorate with each contact. Moreover, these ingredients will also be in contact with perchlorate used in dry food handling equipment such as plastic chutes, conveyor belts, grinders and screens.

Summary

When FDA decided in May 2017 to continue to allow perchlorate’s use as a food additive, the agency relied on flawed science and assumptions with little regard to perchlorate’s potential – and irreversible – harm to a child’s brain.

This prompted EDF and the eight others’ objection to FDA’s decision and request for a formal evidentiary public hearing. We know now, as we did 18 months ago, that it is our duty as public health advocates to challenge FDA’s faulty interpretation of both the law and the science on behalf of our most vulnerable. And it is FDA’s duty to protect public health by ensuring the safety of our nation’s food supply.

The agency must take steps to protect children’s health by stopping the unnecessary use of perchlorate in contact with food. FDA has two choices: either reverse its original decision to allow perchlorate, or give public health advocates the opportunity to argue their case.

And they need to act now.

[2] In its study, FDA analyzed the 2008-2012 data using a new methodology it developed called Clustered Zero-Inflated Lognormal or CZILN. For two-year-olds, the upper bound was 114% of the NRC safe dose. It was 93% for 6 to 11 month-olds and 79% for six-year-olds. In the figure, we used the medians and ranges from FDA’s analysis using an older World Health Organization (WHO) methodology that gave a narrower range. We used the older methodology to compare the 2008-2012 data to the 2003-2006 data because FDA did not use the new method on the older data.

[3] By coincidence, the 2005 samples were collected between October 2004 and September 2005 – before the agency approved the use of perchlorate as an additive to dry food packaging and food handling equipment.

[4] Note that these samples represented a blending of three individual samples from a region of the country so an individual sample could have been three times greater if the others were non-detectable.

[5] Based on FDA representative’s comment at an industry-sponsored law firm seminar as reported in Food Chemical News on October 6, 2011. The article said FDA’s Mike Adams “noted that FDA’s standing assumption has been that there is no migration of polymers from packaging into dry food. Exposure is based on a default dietary concentration of 50 parts per billion. However, evidence from EU lab studies shows substantial migration into dry food, more than 50 ppb in some cases. We’re contemplating a change to require migration studies for dry foods.”

[6] Static is a problem because plastic does not typically conduct electricity and, therefore, allows an electrical charge to build up when solids flow past it. As an analogy, think of spark you get on a dry day when you touch a doorknob after shuffling your feet on a carpet. Small static charge buildups cause powders to cling to the plastic much like the packing peanuts do to your hand when opening a package. Higher buildups can release enough of a spark to trigger a dust explosion under the wrong circumstances.