Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director and Maricel Maffini, Ph.D., Consultant

Around 1990, driven by a concern to keep heavy metals out of recycled products, many states adopted laws prohibiting the intentional addition of arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury to packaging and limited their total concentration to 100 parts per million. Manufacturers and suppliers of packaging and packaging components in these states were also both required to furnish a Certificate of Compliance to the packaging purchaser and provide a copy to the state and the public upon request. The Toxics in Packaging Clearinghouse currently reports that 19 states have adopted this type of legislation.

Out of concern about consumer’s health and contamination of compost, on February 28, 2018, Washington State extended its heavy metal packaging law in a groundbreaking way. The legislature passed HB-2658 banning the intentional use of “perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances” (PFAS) in food packaging made from plant fibers, pending a determination by the Washington Department of Ecology that safer alternatives are available. The law defines PFAS as “a class of fluorinated organic chemicals containing at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom.”

The ban goes into effect in 2022 or two years after the Department makes the safer alternative determination, whichever is later.[1] If, after evaluating the chemical hazards, exposure, performance, cost, and availability of alternatives, the Department does not find safer alternatives by 2020, it must update its analysis annually. We anticipate that this approach will spur innovation among companies offering alternatives and provide a thoughtful and rigorous review of the options.

What are PFAS and why are they in the news?

PFAS are a group of chemicals used in a wide variety of consumer products from food packaging to clothing, shoes, furniture, carpets and cosmetics. They are also used in firefighting foams. These chemicals are used to make water- and stain-resistant textiles, and to grease-proof paperboard for food packaging. The length of the carbon chain and the number of fluorine molecules give the chemicals their sought-after properties but also make them persistent in the environment and the human body.

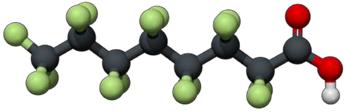

Example of a fully-fluorinated six-carbon PFAS. Carbon is black. Fluorine is green. Oxygen is red. Hydrogen is white.

PFOA and PFOS are the most extensively studied PFAS. They have a chain length of eight carbons, are fully fluorinated (i.e., all the hydrogens in the molecule have been replaced with fluorine), and are present in the bodies of all Americans who have been tested. Research has found PFOA and PFOS associated with an array of health effects in humans and animals ranging from fetal and reproductive toxicity reproductive impairment and cancer.

Concerns with the class of chemicals has exploded in the past two years after EPA released testing results showing PFAS contamination in drinking water in community water systems across the country, usually as a result of source water contamination by industrial operations making or using them. Parkersburg, West Virginia; Hoosick Falls, New York; Bennington, Vermont; Rockford and Belmont, Michigan; and the Cape Fear River area in North Carolina have all struggled with contamination. Chemours, a DuPont spin-off that makes a PFAS by a process known as Gen X at its North Carolina plant, is under pressure to close the facility due to water and air contamination.

Has FDA approved PFAS to be added to food packaging?

PFAS are part of our diet. By EDF’s count, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of PFAS affected by the legislation 38 times between 2002 and 2016 when it reviewed food contact substance notifications (FCNs) submitted by manufacturers. Most uses were for grease-proofing paper and paper board and some included microwavable materials (e.g., popcorn bags). Note that 38 FCNs does not mean that that each was for a unique chemical; some of the approvals were for different uses of the same mix of PFAS, changes in the manufacturing process, or a different mix of the chemicals for the same use. In 2012, at FDA’s request, three companies “voluntarily suspended” interstate commerce of seven approved uses of long-chain PFAS chemicals (i.e., chain of 8 carbon or longer). Six years later, FDA has yet to take the necessary steps to revoke those approvals. FDA has, however, revoked uses of long-chain PFASs the agency had approved before 2000s in response to requests from public interest organizations and from 3M, a former PFOS manufacturer.

In October 2017, EDF submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to FDA seeking the companies’ applications and FDA’s review memos for the 31 active approvals. FDA has provided them in batches; so far we have most of the information for 19 PFAS used in contact with food.

In our preliminary evaluation of the materials, we found that the notifications are lacking important information. For instance:

- FDA’s environmental assessment review was superficial and concluded that the PFAS’ use wouldn’t have an environmental impact. Most companies claimed their products were excluded from the requirement to conduct an environmental impact assessment;

- Companies provided very limited toxicology data, most frequently just in vitro studies of carcinogenicity and, in a few cases, a short-term rodent study;

- Both FDA and the manufacturers were more concerned about whether impurities were mutagens or carcinogens than the toxicity of the PFAS;

- FDA’s review of estimated exposure was more thorough but continued the agency’s flawed approach of assuming the chemicals only contacted food in final packaging and ignoring the possible multiple exposures of raw materials to PFAS across the supply chain; and

- FDA did not appear to consider the evidence that started emerging around 2002 that long-chain PFAS bioaccumulate in humans at rates much greater than in rodents and most (if not all) of them do not degrade in the environment.

Here are the companies that submitted 31 PFAS chemicals food contact notifications to FDA for approval. Follow the links to get more details on the approval.

- Archroma: FCN 1493;

- Asahi Glass: FCNs 599, 604, 1186, and 1676;

- Daikin America: FCNs 820, 827, 888, 933, and 1044;

- DuPont / Chemours: FCNs 510, 511, 539, 598, 885, 940, 947, 948, and 1027;

- Solenis / Hercules: FCNs 314, 487, 518, 542, 746, and 783.; and

- Solvay Specialty Polymers: FCNs 187, 195, 398, 416, 538, and 962.

We plan to share FDA’s FOIA responses upon request from those interested and to provide summaries of each of the approvals in future blogs.

What may be next?

We applaud Washington State for its focus on the health of its residents. Congratulations also to the advocates, particularly Toxic-Free Future and Safer States, who were instrumental to advancing the issue in the state. When it comes to food additives and food contact substances, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act does not preempt states taking action. When the federal government is unwilling or unable to act, we anticipate that other states will take an increasing role in protecting public health.

[1] Washington State passed another law that banned PFASs in firefighting foam.