Natural infrastructure solutions demonstrate measurable flood risk reduction: A case study of the Prairie Creek Watershed

Flooding is a growing issue for communities across the United States. And the challenge is not just coastal. In recent years, inland communities that sit near rivers and waterways have experienced more frequent and intense flood events, causing infrastructure damage, social disruptions and economic losses. Much of this can be attributed to the increases in precipitation combined with declines in watershed health of the surrounding lands due to development and agricultural use.

Take for example the communities along the Mississippi River or one of the interconnected waterways in its river system. These rivers and streams support good-paying jobs, economic vitality and community for millions of people. Yet, the proximity to the rivers and streams also mean high challenges with flooding. Cities like Cedar Rapids, Omaha and Fremont and more have experienced devastating flood events when extreme rainfall struck the area.

On top of this, precipitation in the region is increasing. Over the last half century, the average annual rainfall in most of the Midwest has increased by 5 to 10%. Future rainfall predictions show an added 5-11% increase in flooding (flood inundation) in certain watersheds. Bigger storms mean more people, homes, businesses and public infrastructure are at economic risk.

Leaders across the Midwest and in other parts of the U.S. are doing critical work to reduce flood risk from extreme weather events. A great example is the city of Cedar Rapids, who has made tremendous progress to reduce their flood risk after the deluge of 2008. Yet more work is needed to protect all communities, especially those in low-income areas. As leaders work to build resilience in their communities to withstand more frequent and intense storms and the subsequent higher flood risks, many may want to consider how working with nature can be complementary to engineered solutions.

Natural infrastructure solutions offer tremendous flood benefits. While these solutions have mostly been considered for their water quality and habitat restoration benefits, many natural infrastructure measures mimic and enhance natural water storage capabilities and reduce runoff upstream, effectively mitigating flooding downstream.

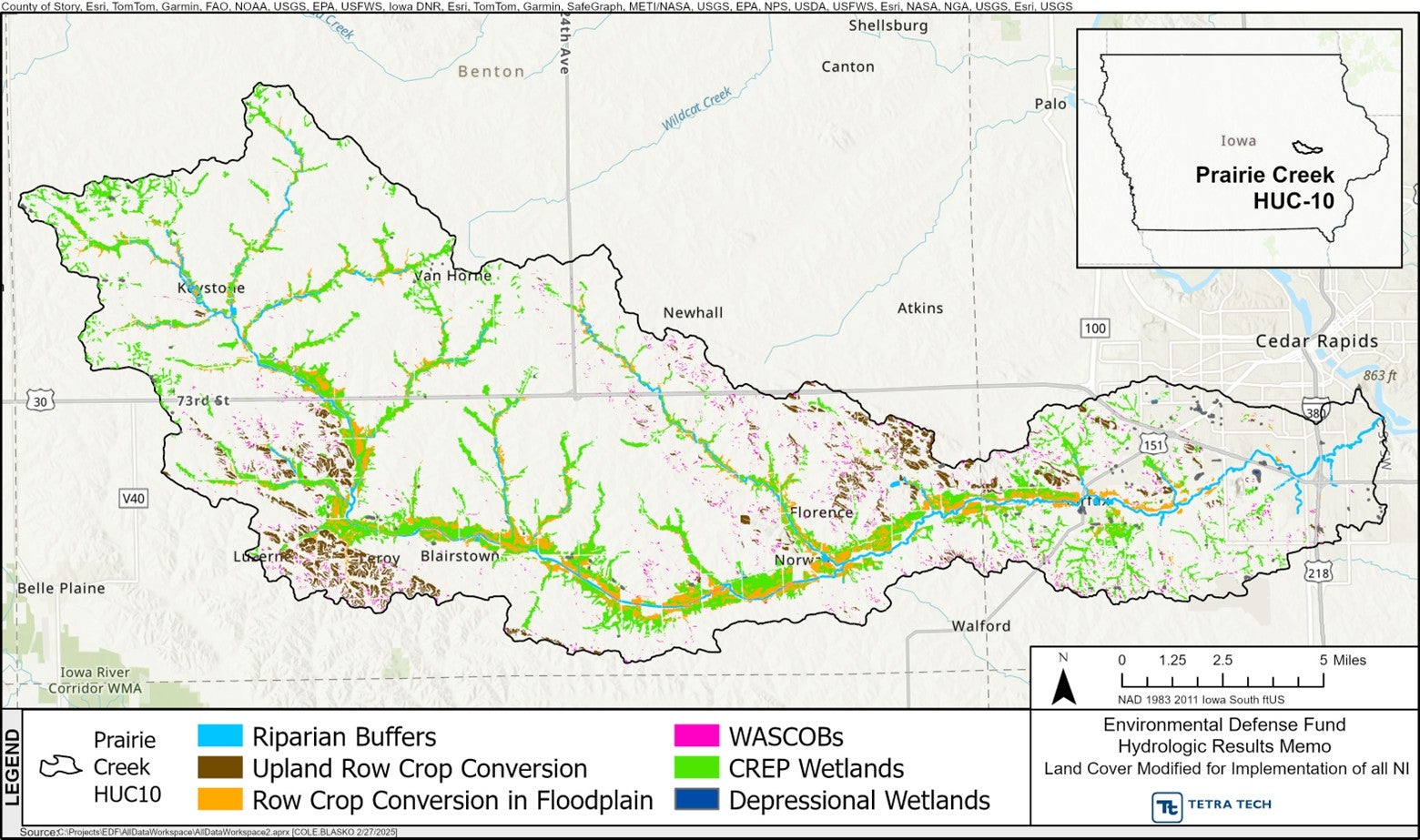

To better quantify the flood benefits of natural infrastructure solutions, Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) recently completed a new study that examines a single watershed in the Mississippi River Basin, looking at present and future storm conditions and how natural infrastructure would reduce flooding from these storms. The Prairie Creek watershed sits just south of Cedar Rapids, Iowa with its headwaters running through primarily rural agricultural land and the river’s outlet passing through a more urbanized area. The rural upstream region presents many potential locations to implement natural infrastructure practices that store water.

Using publicly available data, the report looks at major storms of varying levels (i.e., 10-, 25-, 50-, 100-, and 500-year storms) in present (2024) and future conditions (in years 2036-2065) and models the flood impact scenarios in downstream communities with and without natural infrastructure implemented across the watershed area at varying degrees of scale: 2.5% (3,423 acres), 5% (6,846 acres), 10% (13,691 acres) and 17.2% (23,627 acres) of the landscape. The report further uses a publicly available economic flood damage estimation tool called Hazus to calculate the net value of avoided losses when natural infrastructure practices were implemented at these different scenarios.

Natural Infrastructure (NI) Solutions That Can Reduce Flood Risk:

The majority of the land in the Prairie Creek Watershed is privately owned agricultural land, which mirrors the ownership make-up of land across the larger Basin. Given agriculture’s importance in the region, EDF looked specifically at natural infrastructure measures that do not require a large swath of cropland conversion, but rather can be implemented on marginal land while producing great environmental benefit. These natural infrastructure measures include:

- CREP wetlands – Converting land to wetlands via the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), a long-term conservation cost-share assistance program administered by the Farm Service Agency (FSA).

- Depressional wetlands outside the floodplain – Restoring wetlands located in natural depressions outside the floodplain i.e., prairie potholes).

- Riparian buffers – Creating vegetated areas adjacent to a body of water (i.e. pond, river or stream) that intercept runoff. Riparian buffers do not provide floodwater storage but mitigate flooding by reducing runoff velocity and enhancing water infiltration.

- Row crop conversion on highly erodible land – Converting highly erodible row crop land (i.e., on slopes greater than 7%) to native grassland/prairie to reduce runoff velocity and enhance water infiltration.

- Row crop conversion within the floodplain – Converting land used for conventional row crop production located within the floodplain to native prairie.

- Water and sediment control basins (or WASCOBs) – Creating small earth embankments on agricultural land that collect and store runoff from concentrated flow paths.

Report Findings

The study found that implementing natural infrastructure solutions in upland areas exhibit quantifiable effectiveness in reducing flooding in downstream communities in both present day and future storm scenarios.

- The results show natural infrastructure solutions can significantly reduce peak water discharge, by nearly 50% in some cases. Notably, naturally infrastructure solutions are particularly effective in reducing flood levels downstream during moderate sized storms, or storms that are more likely to occur yet still significant (i.e., 10-, 25-, 50-yr storms). For example, implementing natural infrastructure solutions reduced peak flows of a 50-year storm to levels less than that of a 10-year storm without natural infrastructure.

- There is no clear threshold at which natural infrastructure solutions become more effective relative to the extent of implementation–as more instances of natural infrastructure solutions were implemented across a watershed, reduced flooding increased on the same trend.

- CREP wetlands stood out as the most effective solution for its potential to store substantial flood waters, among the natural infrastructure solutions reviewed.

- Average annual losses due to flooding could be reduced by up to roughly one-quarter (25%) with the implementation of natural infrastructure in a watershed. The report, for the first time, puts a figure on the potential economic savings thanks to natural infrastructure. Across all scenarios, natural infrastructure implementation could reduce total economic losses by roughly 25%. Additionally, when natural infrastructure solutions are fully implemented (17.2%) across a watershed such as Prairie Creek Watershed, the savings rose to nearly one-third (32%). Accounting for the upfront cost of implementing the natural infrastructure solutions, the overall economic benefit to communities could be $884 million.

- Implementing natural infrastructure on the lowest level simulated (2.5%) achieved nearly twice the economic benefit of other implementation levels. This is likely because economic benefits compared to the cost of implementation were relatively the same whether solutions were implemented on 2.5%, 5% and 10% of the landscape.

The good news is, across the Mississippi River Basin, the studied natural infrastructure measures are already being implemented by leaders in the agricultural community to address water quality needs. This report showcases that these solutions offer expanded benefits, in the form of flood reduction. Leaders can consider how they can increase funding opportunities for these natural infrastructure solutions as well as coordinate implementation efforts in key watersheds where scale would be beneficial for flood reduction needs.

View the full report HERE.

View the executive summary HERE.