Drought in California is intensifying. It’s time to rise to the challenge.

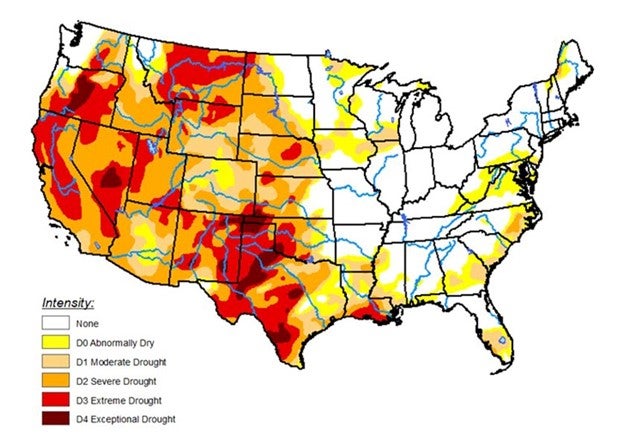

Record-setting high temperatures in the 90s — in April. The driest first three months of the year in California history. Another drought executive order from the governor calling for more water conservation and requiring protection of existing groundwater wells. These are all signs that the drought is continuing to rear its ugly head in our Golden State and indeed much of the West.

On top of that, the recently released climate report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that if we don’t get serious about making “immediate and deep” cuts in emissions everywhere, the impacts — including droughts — will become even more severe.

But that report also offered hope, noting we still have the tools and sufficient capital and liquidity to limit warming and its impacts. Similarly, in California, we are fortunate to have a mammoth $29 billion budget surplus this year. If deployed effectively, this windfall gives the Newsom administration and state leaders the unique opportunity to help the nation’s most productive agricultural region successfully transition to limited but more resilient water supplies in an equitable way.

The days of narrowly relying on one single solution to address our water challenges — like the aqueduct and reservoir projects of the last century— are a thing of the past. Today we need to invest smartly in a wide range of 21st century solutions that address both supply and demand and achieve a wide range of benefits for people and ecosystems.

We need realistic estimates of sustainable groundwater supplies.

On the supply side, we should be implementing projects now so that we are prepared to capture water and recharge our aquifers, a critical form of natural infrastructure, when the next storms arrive, as they eventually will.

While there are promising opportunities to recharge groundwater aquifers, we need to be realistic about what we can grow, over how many acres, and how to use the remaining lands where there isn’t enough water to sustain crops.

Earlier this year, the California Department of Water Resources ruled several groundwater sustaining plans incomplete for a variety of reasons, requiring local agencies to revise those plans within 180 days. In response, local groundwater agencies need to provide growers with a clearer expectation of what their groundwater future holds. Plans should be revised to provide a realistic estimate of available supplies and, therefore, what the expectations are for ramping down pumping so that growers can plan accordingly.

High interest in farmland repurposing is a positive sign for demand reduction.

As we work towards bringing groundwater basins into balance, setting clear expectations about supply and demand needs to be tied to providing growers with as many options as possible for managing their lands and water, including well-designed water trading programs and land repurposing programs. Fortunately, this has already started to happen. One encouraging sign: the strong, positive response to the Department of Conservation’s new Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program,

In its first round of applications, due April 1, the department received more than $100 million in proposals — more than twice the initial $50 million in funding approved by the Legislature and governor. The department is still reviewing their eligibility.

This response is particularly encouraging because these applications were completed as some agencies were in the midst of responding to DWR’s finding that their groundwater plans were incomplete. There is clearly even more demand because some groundwater agencies have said that they didn’t have capacity to work on both the land repurposing applications and updating their groundwater plans, so they plan to apply for land repurposing grants during the next round of funding.

The new program provides funding for landowners to repurpose some farmland to other uses such as multibenefit groundwater recharge basins, habitat corridors for wildlife, and open space for disadvantaged communities. All of these alternative uses are critical components of a sustainably managed groundwater basin.

Receiving applications for twice the amount of available funding suggests that many water managers and landowners accept the difficult reality that California’s agricultural footprint will need to decrease to ensure we have enough water for future generations of both people and wildlife.

We need more funding to incentivize farmers to conserve water.

The strong interest in the new program also demonstrates that far more funding is needed to support communities through this landscape transition, as the Newsom administration recognized last year when it initially proposed $500 million to start the program. Most recently, the administration has proposed $40 million in the next budget, which the latest application pool demonstrates is clearly not enough.

The Public Policy Institute of California has estimated achieving groundwater sustainability in the San Joaquin Valley requires taking about 750,000 acres of farmland out of production. This means the scale of funding to support rural communities through this transition is in the billions of dollars.

Watch the May budget revision for more drought actions.

We hope that state leaders rise to this billion-dollar challenge when Newsom releases his May budget revision and outlines plans for $250 million he has proposed for a drought reserve to be allocated this spring, based on conditions and need.

The good news is California currently has the money to support rural communities and farmers through this transition. As we stare down another bone-dry year, let’s make sure we are being proactive and smart about how we spend those dollars.