Why Kansas farmer Justin Knopf strives to emulate the native prairie

I first met Justin Knopf at a meeting in DC about five years ago. At 6’3”, he definitely stood out, but not just physically. He openly conveyed how important his family and his land are – the reason he cares so much about making sure his Kansas farming operation can live on is for his children. It’s rare to meet someone so articulate, sincere and committed to sustainability.

I first met Justin Knopf at a meeting in DC about five years ago. At 6’3”, he definitely stood out, but not just physically. He openly conveyed how important his family and his land are – the reason he cares so much about making sure his Kansas farming operation can live on is for his children. It’s rare to meet someone so articulate, sincere and committed to sustainability.

Over the years, I have become more and more impressed by Justin, who started farming at age 14 when his father gave him the means to rent land and buy seed and fertilizer.

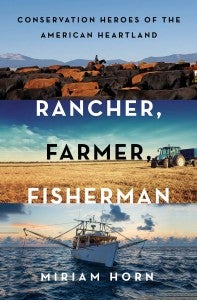

Fast forward to today, and Justin is one of the country’s champions of no-till farming – a practice that has boosted his yields and made his crops more resilient to the effects of extreme weather. His dedication and success caught the attention of Miriam Horn, author of the new book Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman: Conservation Heroes of the American Heartland.

Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman tells the stories of five individuals in the enormous Mississippi River watershed (Justin included) who are embracing sustainability and defying stereotypes. I asked Justin about the book, his beliefs on sustainability and what’s next for no till.

Why did you decide to be a part of Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman, and to tell your story?

It was a difficult decision to be so transparent with whoever decides to read the book. It’s a fairly vulnerable situation to put yourself in, but I believe strongly in transparency – and our neighbors across the country are hungry for transparency in our agricultural system.

“I have an obligation to take care of the people around me, such as my family and my community, and also the natural resources that sustain us.”

As more of our country becomes further removed from the farm, it becomes easier for folks to believe whatever they might read on social media or in marketing campaigns about farms in the heartland. We’ve made plenty of mistakes in farming, but this notion that our nation’s agricultural system has been overrun by these so-called “factory farms” that are forsaking the environment and our natural resources just to fill their pockets really bothers me.

My hope is that this book will bridge some of the disconnect and improve trust between those of us working with the land on a daily basis, and those at the other end who are consuming our products. Many farmers are seeking out and implementing innovative ways to improve their soils and natural resources while still improving productivity.

Do you consider yourself a conservationist?

The short answer is yes, but I believe it’s important to define what I mean by conservationist. It seems words like these can have so many labels and different connotations attached to them. To me, being a conservationist is first about having perspective – a long-term perspective that recognizes the bountiful resources we have must far outlive our lifetimes. And second, while we are only a tiny part in the long story of time, the choices we make have long-term impacts. Then conserving these resources becomes a constant undertone influencing the choices I make.

I have an obligation to take care of the people around me, such as my family and my community, and also the natural resources that sustain us. It’s important to take care of them and try to be as restorative as possible.

In terms of climate change, whether or not farmers agree on the cause is somewhat irrelevant. We will all have a responsibility to become more resilient. In other words, climate change or not – sustainability helps ensure the longevity of our businesses.

The book notes that you have seen little benefit from planting cover crops; why do you keep planting them?

I’ve seen very little economic benefit – maybe even a negative short-term economic loss from cover crops. But the reason I keep planting them and trying to learn where they best fit in our cropping system goes back to resiliency. I’m taking the long-term look at my operation and trying to build more diversity into our biological system.

I’ve seen very little economic benefit – maybe even a negative short-term economic loss from cover crops. But the reason I keep planting them and trying to learn where they best fit in our cropping system goes back to resiliency. I’m taking the long-term look at my operation and trying to build more diversity into our biological system.

It might take a generation of observation before this and other practices become widespread. But I believe cover crops are part of the path forward on our farm because they can, among other things, impact water holding capacity and improve the infiltration of our soils. However, in other environments, they may not be the best fit. I have a good friend in western Kansas who has experienced significant yield loss in crops following cover crops. Yes, cover crops can increase infiltration, but they also utilize water to grow and in drier climates that water may not be replenished in time for the following crop. So, as always, a biological system is complex, and what’s the right choice for one environment may clearly not be the right choice for another.

What about no-till… adoption rates are still low. What trends are you seeing?

“I’m taking the long-term look at my operation, and trying to build more diversity into our biological system.”

Much of farming is about economics and risk. Right now I would say we’re not seeing much of an uptick in no-till farming given low commodity prices. When we experience low or even negative margins, everyone – not just farmers – has a tendency to revert to what we’re comfortable with. It can be risky to make a big change.

But, I hope other producers will see the value in no-till and that we’ll see increased adoption rates. Also, the transfer of farms across generations typically leads to change – another time when we’ll see a surge in no-till. In the meantime, there are some great resources such as No-till on the Plains, an organization that provides resources, education and networking not just on no-till, but on all elements of production systems that model nature.

What’s the key thing you’d like readers of Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman to come away with?

I hope readers are reminded of the abundance, beauty, awe and importance of the Mississippi watershed. The heartland has been foundational in shaping our nation’s abundance, literature, politics and identity.

For urban readers who have perhaps felt a little disconnected from the middle of our country, I hope it restores a strong sense of pride in our heartland and hope for our future.

For those of us readers who get to work daily with the abundance of our heartland, I hope it evermore increases our commitment to stewardship and giving the land, water and resources the dignity they so deserve.

Further reading:

These heartland conservation heroes defy stereotypes >>

A coalition of uncommon bedfellows is bringing sustainable agriculture to scale >>