Where Is All Of The Water Going? A Look At Which Energy Resources Are Gulping Down Our Water

If you’re like so many conscientious consumers, you’ve experienced the disappointment that comes when you realize the lean turkey breast you bought has 300% of your daily value of sodium, negating the benefits of its high-protein and low-fat content. Instantly, food choices feel more complex; you’ve learned the hard way that the pursuit of a low-fat diet is not the same as a healthy diet.

The Energy-Water Nexus shows us that our energy choices are much like our food choices: The environmental benefits of an energy diet low in carbon emissions might be diminished by increased water consumption (or waste), and the unforeseen tradeoffs between the two resources (i.e. more sodium in lieu of less fat, can hurt us in the long run).

Water Intensity

As we have mentioned before, roughly 90% of the energy we use today comes from nuclear or fossil fuel power plants, which require 190 billion gallons of water per day, or 39% of all U.S. freshwater withdrawals (water “withdrawal” indicates the water withdrawn from ground level water sources; not to be confused with “consumption,” which indicates the amount of water lost to evaporation.)

The water intensity of these energy resources brings us face-to-face with the realities of energy and water overconsumption. High electricity consumption means more water withdrawals, placing extra strain on the water system. At the same time, emissions from power plants contribute to climate change, which increases the amount of water required to produce energy and intensifies severe drought.

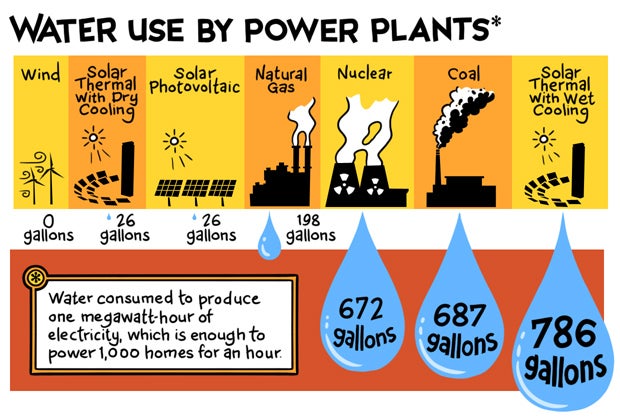

It’s important to realize that our energy choices have a part to play in these dire situations. Let’s look at a breakdown of how energy resources stack up in terms of water consumption and discuss their carbon footprints:

Wet-cooled concentrated solar power plants use slightly more water than coal and natural gas; however, concentrated solar power plants can be designed to use dry-cooling, thereby reducing water demand by more than 90%. Additionally, solar thermal produces zero carbon emissions.

- Coal generally requires more water than nuclear, and generates more greenhouse gases emissions and other pollutants than any other energy source (about 2.15 lb CO2 per kWh electricity), making coal something like the chili cheese fries of energy.

- Unlike coal and natural gas, nuclear energy releases no carbon emissions, but still requires an abundant water supply – think about that high-sodium processed turkey.

- Natural gas emits about half the carbon emissions of coal (about 1.22 lb CO2 per kWh electricity) and requires less water than coal, but still needs an enormous amount of water for drilling activities and conversion to electricity.

Texas

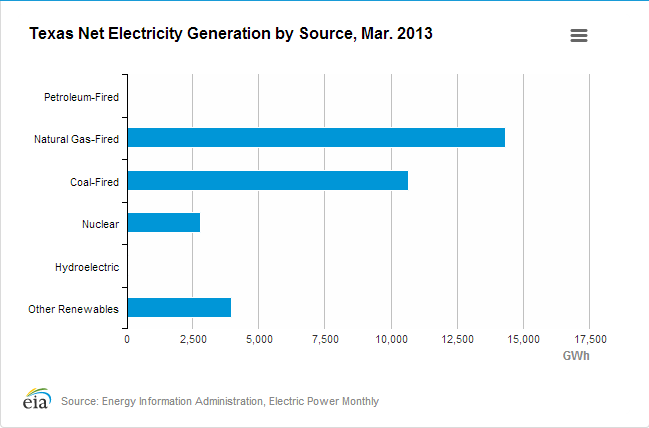

If you need an example of a state that is currently coping with realities of the energy-water nexus, look no further than Texas. The state is currently in the midst of a multi-year drought, yet the vast majority of the electricity Texans use comes from sources that contribute to this prolonged drought (namely, natural gas, coal and nuclear). With nearly 90% of Texas’ electricity coming from these three sources, we have a serious problem.

Here’s a breakdown of fuels used in electricity production in Texas:

These water-intensive power plants consume thousands of gallons of drinking water per day, while roughly 90% of the state remains in drought conditions. The ongoing water shortage has prompted 65% of Texas counties to impose water use restrictions, and even forced some communities to truck in fresh drinking water several times a day. And don’t forget, Texas’ vast fleet of coal and natural gas generators contribute to our shameful ranking as number one carbon emitter in U.S.

No matter what, when it comes to fossil fuels, there will always be a hidden environmental consequence—much like the sodium hiding in your ‘lean’ turkey. There are, however, guilt-free, low-water options: renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Solutions

Wind energy and solar photovoltaics (PV) consume little to no water and generate negligible carbon emissions. Texas, already an international leader in the use of wind power, should increase use of its clean energy sources to cope with the continuing drought and the ongoing Texas Energy Crunch.

At the same time, the state should look to energy efficiency to reduce water use and cut carbon pollution. The more we invest in energy efficiency, the more we cut our overall energy use—saving enormous amounts of water and reducing harmful power plant emissions. After all, the cleanest source of energy is the energy (and water) we don’t use.

However, Texas, and other states, has a long way to go before decision-makers tactically conserve its water supply and utilize the best available energy technologies, and I intend to take a more in-depth look at Texas in my next post. Stay tuned!

This is one of a group of posts that examines the energy-water nexus, Texas’ current approach to energy and water policy and what Texans can learn from other places to better manage its vital resources.

5 Comments

Excellent post. It is awfully sad that a state like Texas – with great potential for renewables – has such backward political leadership. Making the connection between drought and energy usage is really important if they are to change their ways.

I feel like this article confuses water withdrawals and water consumption. Almost all water used for cooling — which is most of the water use for energy generation — is returned uncontaminated to the water source, with the only change being an increase in temperature.

You explain the difference between withdrawals and consumption, but in the next paragraph, say “The water intensity of these energy resources brings us face-to-face with the realities of energy and water overconsumption.” But you just got through pointing out that energy production withdraws a lot of water, but doesn’t necessarily consume it, so using the term “overconsumption” is misleading.

I’m all for green energy, but I think it’s important not to weaken all the strong arguments for investment in renewables by referencing the science inaccurately.

Sasha, thank you for your comment. You raise an excellent point. The second use of the word “consumption”, referencing energy and water overconsumption, was not actually in reference to consumption of water by power plants but to our overall overconsumption of energy and water. That is, we’re not being efficient in our water or energy use. I agree that the use of the word could be misleading in this context– thank you for pointing that out. Kate

Why do these power plants need to use drinking water? Wouldn’t they cool just as effectively with non-potable water, salt water or sewage?

@Patrick, your idea is very good, by sewage il probably the last thing you’d need to cool down a power plant, because it is really disgusting (I used to work in the sewage treatment) and contains a lot of stuff that would give troubles to the technologies involved (starting with simple obstructions, ending with something worse… you don’t want to give bacteria some heat). It would be a good idea to use sewage water after it has been treated, but at that point it is just one little step below drinking water (if the treatment was right).